When I was a young and poor college student and wanted to buy a classical music LP, I was faced with a choice. Most of the biggest names in the field recorded for one of the major labels: Deutsche Grammophon, Decca, Columbia, RCA or Angel (aka EMI). And those disks were pricey.

In some cases, I would just have to suck it up and spend more than I really should have. But there was an alternative. There were budget labels, offering their records at cheapie prices.

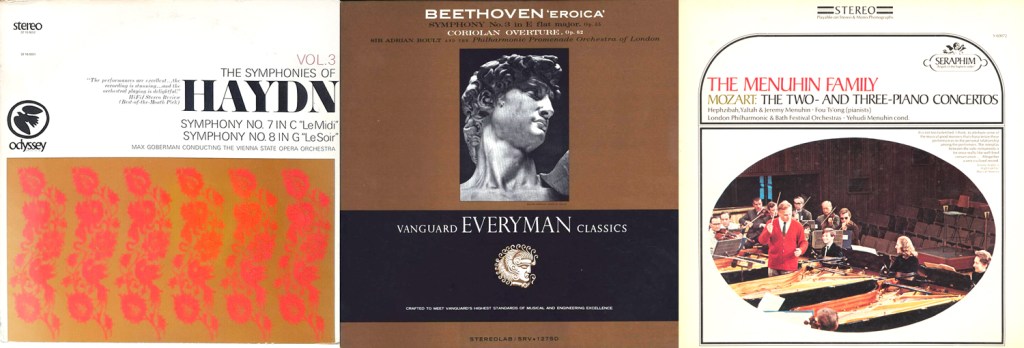

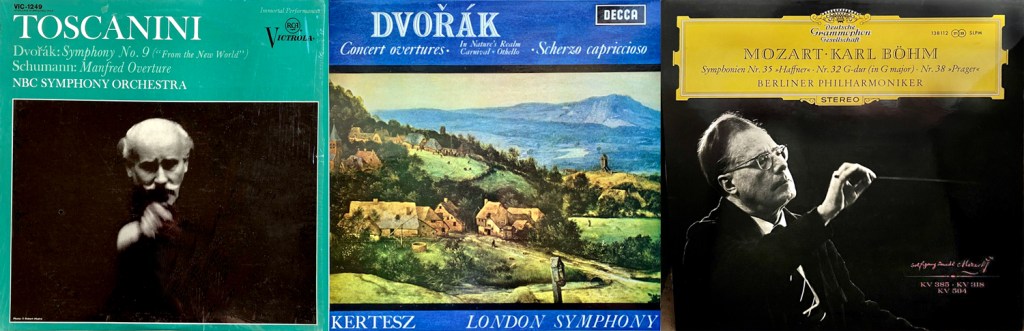

Most were sub-labels of the pricier brands, as Seraphim sold older versions of Angel releases, or Victrola from RCA and Odyssey for Columbia. And Vanguard Everyman. And there were some bottom of the barrel labels, with really poor recordings of Eastern European, and Russian musicians, such as Melodiya and Urania. Those sounded awful.

And their album covers were usually cheaply designed, or copies of how the premium brands showed themselves, with photos of the conductors or musicians, or with pretty landscapes. After all, classical music was serious. It was art.

But then came the Baroque revival, and instead of Beethoven symphonies, we were offered Vivaldi, Telemann and Monteverdi madrigals. The Sixties were in full swing, the budget labels dove into bright, colorful, more lively album covers, often with whimsical illustrations.

These were Nonesuch recordings and the Vox budget label, Turnabout. My collection was full of them

There were two labels in particular that went for the comic and the hip. Westminster and Crossroads. The created memorable cover art, but took very different paths.

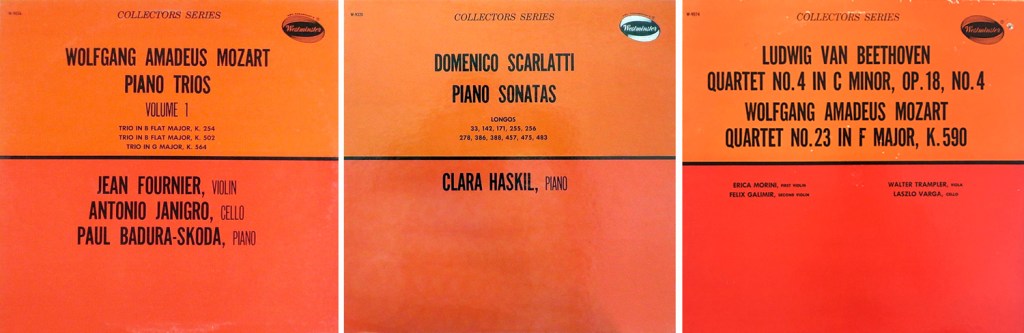

Westminster Records began life in 1949 as a high-end audiophile label, but by the time I came to know them, they were a low-end budget brand, and their covers were as simple and unadorned as the “plain brown wrapper” that used to hide racy novels. Those red covers, with a horizontal black line were easy to spot in the record store bins, and for those of us on a limited budget, an instant look-see. The performances were generally very good, if by musicians more noted more in Hungary or Poland than in Carnegie Hall. They were dependable. I owned bunches.

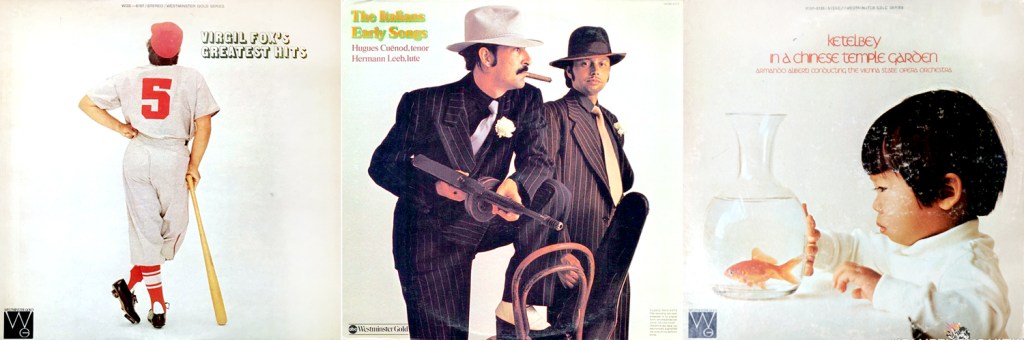

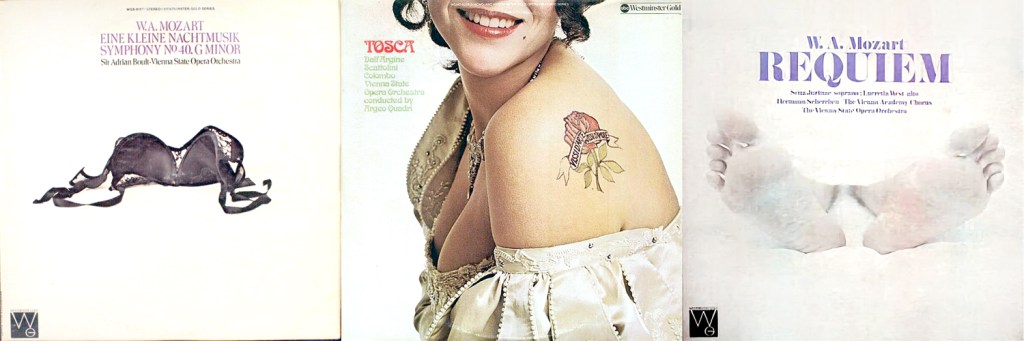

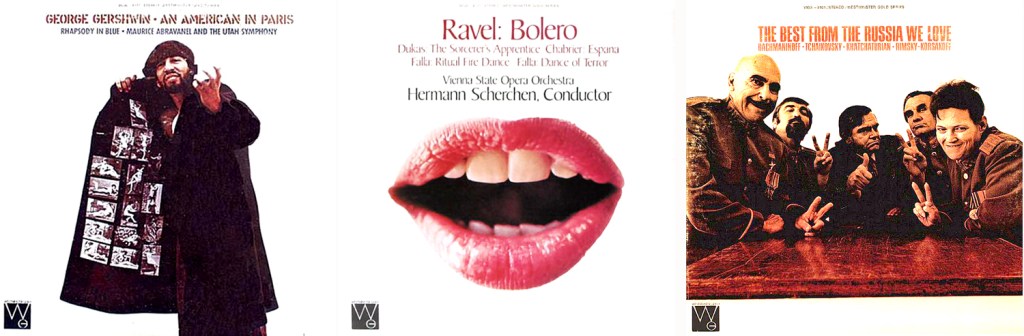

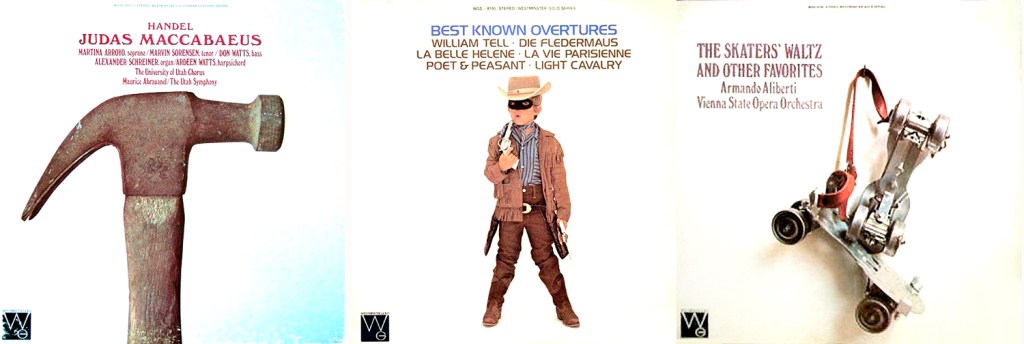

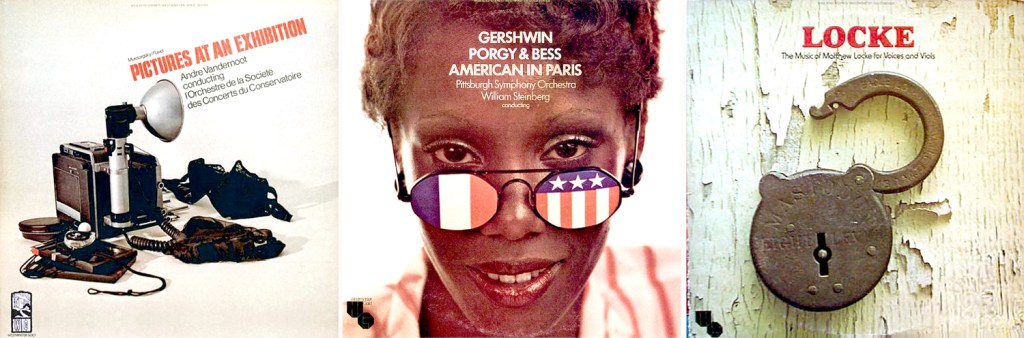

But, the label was bought out by ABC-Paramount and by 1970, they began marketing their back-issue catalog with sometimes ridiculous and campy cover art. To attract the kids, I guess.

They included a Beethoven concerto with a busty brunette, whose busts were those of the composer, strategically placed. Or Ferde Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite with a faux Georgia O’Keeffe cow skull, or — my favorite — a Barbarella knock-off of cheap sci-fi for Gustav Holst’s Planets.

(Click on any of these images for a clearer look)

These covers are now collector items for a memorable gallery of time-stamp art. I have gathered images of well over a hundred of these gems, and thought I should share a few of them.

Westminster sold the 1968 Hans Swarowsky Nuremberg Ring Cycle with Carnaby Street Valkyries, Rhine Maidens and Norns.

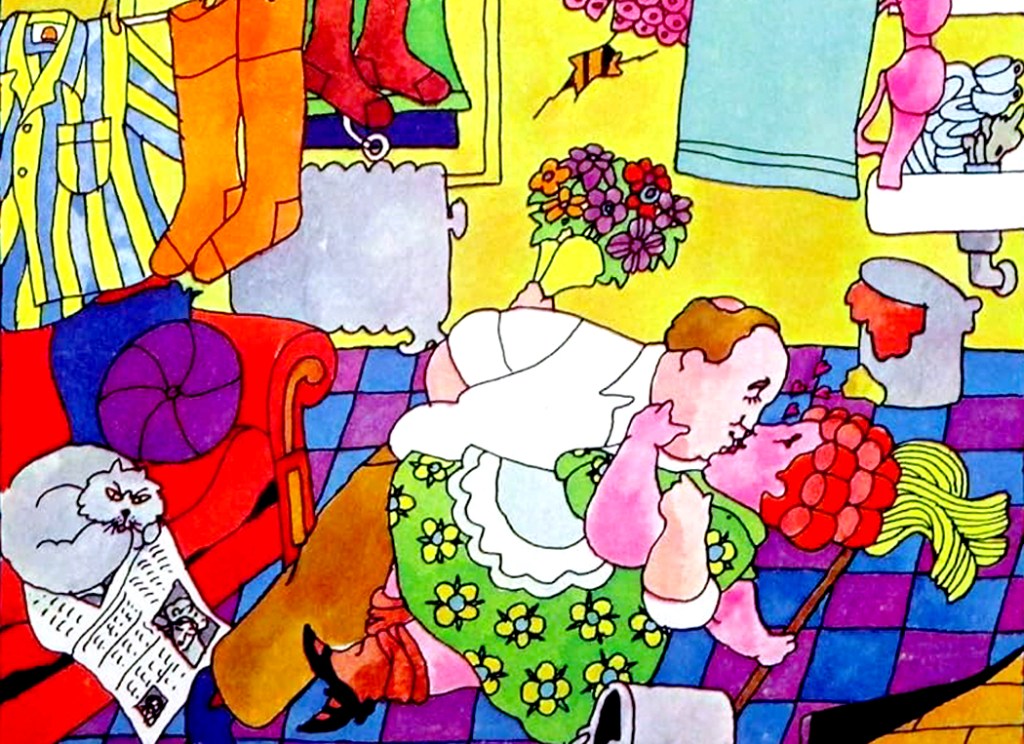

And there was the two-disk recording of Berlioz’s Romeo and Juliet, coming out hot on the heels of the Franco Zeffirelli film starring Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting. Could this cover be a coincidence? See the image at the top of this column. The album folds open to give us the whole picture (Love those socks).

Then, there is organist Virgil Fox’s “Greatest Hits,” with the baseball player; traditional Italian songs with, of course, just the kind of mafiosi who regularly croon such tunes; and to round out the ethnic stereotypes, there is Albert Ketelby’s In a Chinese Temple Garden. Subtlety is no object.

Then, there’s the sex and death contingent. Although what a cast-off bra has to do with Mozart is hard to tell. Tosca, though, surely liked to show off her décolleté, although I am unaware she ever had a tattoo. The obvious follow-up is a requiem.

For some reason, the recording of Baroque flute and harpsichord sonatas shows us a bassoon and cello. And if you are going to have opera without words, you need a horned helmet and bandaged mouth. And there’s the merry widow drinking wine on a coffin.

Haydn’s clock symphony, some Beethoven trios (apparently for teddy bears), and Bach cello sonatas.

An American in Paris, selling risque pictures, a lipstick Bolero, and a gang of Russians selling us Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky.

Judas Maccabaeus was known as the Jewish Hammer, so, OK. The William Tell Overture has its connotations, and the Skaters’ Waltz is obvious.

Pictures at an Exhibition needs a camera; Porgy and Bess share a disk — and eyeglasses — with an American in Paris; and, if the composer is Matthew Locke, you clearly had no choice.

There are many more, just as hokey, corny, and campy. As I said, I have about 130 of them in my files.

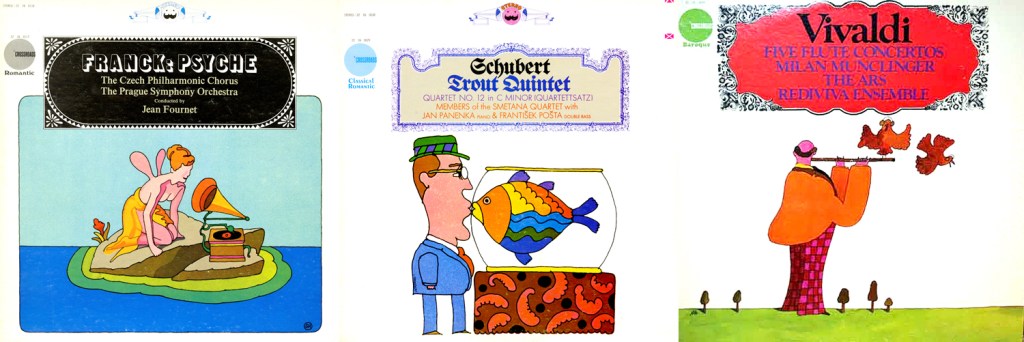

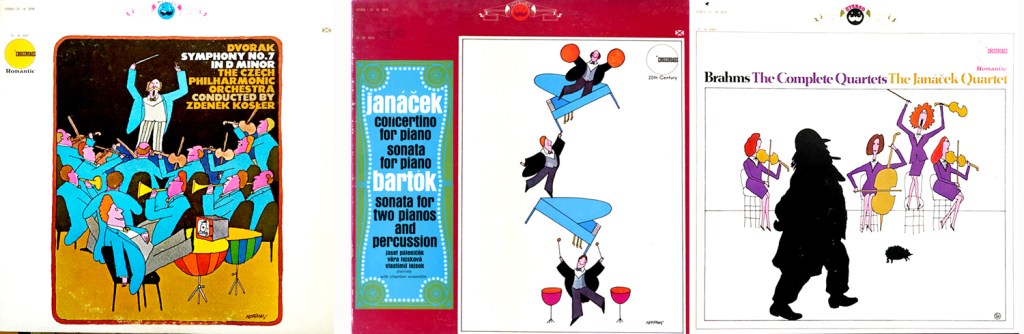

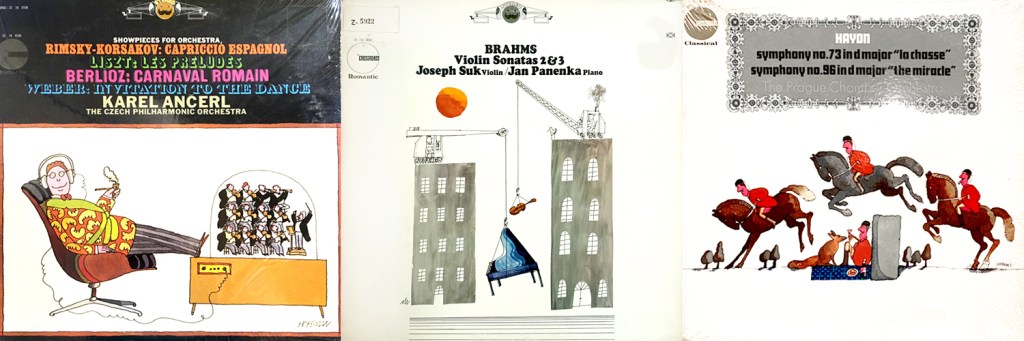

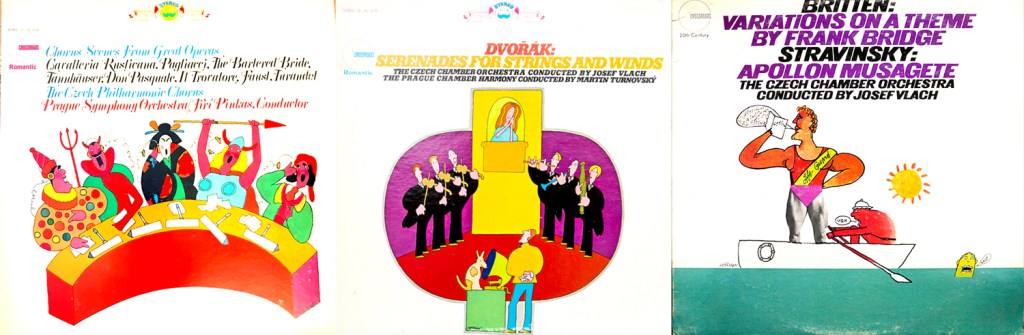

But, it is the other label I really like better. Crossroads was a subsidiary of Epic Records. Epic dealt mostly in popular music and jazz, but in the late 1960s, they licensed reams of Supraphon recordings, mostly recorded with Czech musicians, and sold them under the Crossroads label, with often quite witty cartoon album art. The level of performance was top-notch, with some of the world’s best soloists and orchestras.

I have gathered about 70 Crossroads album cover images, and offer a few here.

The Prague Madrigal Singers recording of Brahms Liebeslieder Waltzes was the perfect performance, light, with a happy amateur feeling of a group of friends singing together. Other recordings I have owned were too operatic and artsy for Brahms’ gemütlich bourgeois lovesongs. And the cover art perfectly reflected the tone of the performance, and of the music Brahms wrote:

Unfortunately for me, this performance has never shown up on CD and I long ago got rid of all my LPs.

Many of the other Crossroads releases have subsequently been rereleased on other labels, including the original Supraphon recordings. But the album covers of the CDs never quite match the joie of these LP covers. It is also obvious that these came out about the same time as the animated Yellow Submarine movie. The style is unmistakeable.

There’s a bit of Hokusai’s Great Wave in this Debussy. More Yellow Submarine for unknown classical-era composers and Someone has to vacuum up all the dropped notes.

There is, of course, a lot of Dvorak and Smetana in these Crossroads releases.

But it’s not all Czech. Here’s some Franck and a great Schubert “Trout” quintet. And even some of the musicians are not Czech. There are Germans, too.

The covers are a delight, even for heavier music: Dvorak’s most Germanic symphony, Bartok raucous Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion and the deep slog of going through Brahms’ string quartets.

Villa-Lobos, Milhaud and others; Schubert’s giant op. 99 Trio; and 18th century Bohemian composer Jan Voríšek, apparently having his tooth pulled.

Listening to the Loud Classics on earphones; two Brahms violin sonatas (you cannot find a better performance than the great Josef Suk and pianist Jan Panenka; I owned this LP for years — a delight); and Haydn’s “Chase” symphony.

The tradition of budget recordings continued into the CD era, with some super-cheapie labels, such as Pilz and Laserlight, and there was a deluge of rare repertoire items that came out on Naxos, before that label went upscale. And the classical music recording industry has just about collapsed with fewer new recordings, but a raft of back-catalog items being issued in budget boxes by Sony, Warner, and Brilliant, often for as little as a buck a disk.

And now that I am retired, I find myself back in the same situation I was when I was newly graduated from college and making $50 a week at a retail store (well, not quite that bad off), and I find myself again stocking up on piles and piles of budget issues.

Click on any image to enlarge