I want to put in a good word for TV sitcoms. They don’t get much respect. And it is true that many of them are routine, uninspired and forgettable. “Chewing gum for the eyes.” But the genre as a whole has both a long history (longer than you may suspect), and a significant role to play in the arts. Yes, the arts.

What we call art is a lot of things, and serves many purposes, but one thing all art, whether painting, music, theater or literature, is asked to do is entertain. There are different levels of entertainment, but even Joyce’s Ulysses or Berg’s Lulu offer an underlying level of amusement.

Comedy players, Mosaic from Pompeii

Some offer much more, but the base line of keeping us interested has been there from the earliest times we have record of. And much of it even fills university courses. We study Plautus and Terrence — among the earliest sitcom writers (Rome, 6th century BC), with plays full of dirty old men, unfaithful wives, clever slaves, mistaken identities and love-struck young men.

There are few actual characters in such plays, and a great panoply of stock figures. These kinds of figures, stuck in difficult and comic situations, populate the works of Italian commedia dell’arte, the comedies of Molière, and the plays of Shakespeare (who would sometimes borrow from Plautus and Terrence). Victorian novels — by Dickens, Trollope, Thackeray — now treated as literature, were at the time serialized in popular magazines and thought of much the same as we now consume TV shows. And all now deemed worth of academic study and even reverence.

So, why not the same for All in the Family or The Honeymooners? Are they any “lower” an art form than The Twin Menaechmi? Or The Braggart Soldier?

Remember, Shakespeare’s audience included the uneducated groundlings; he wrote also for them. And he was not above the traditional fart joke. It ain’t all Seneca and Henry James.

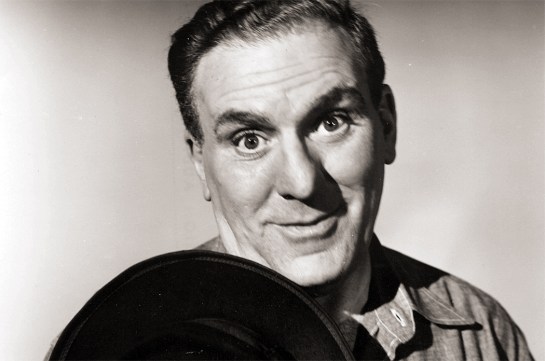

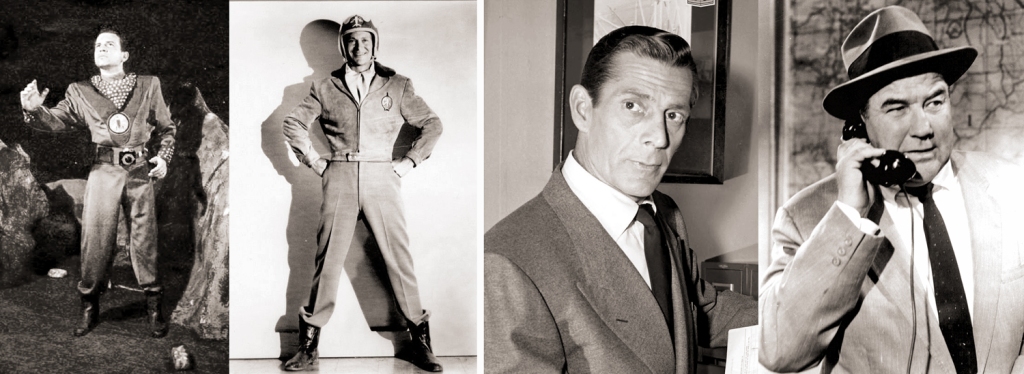

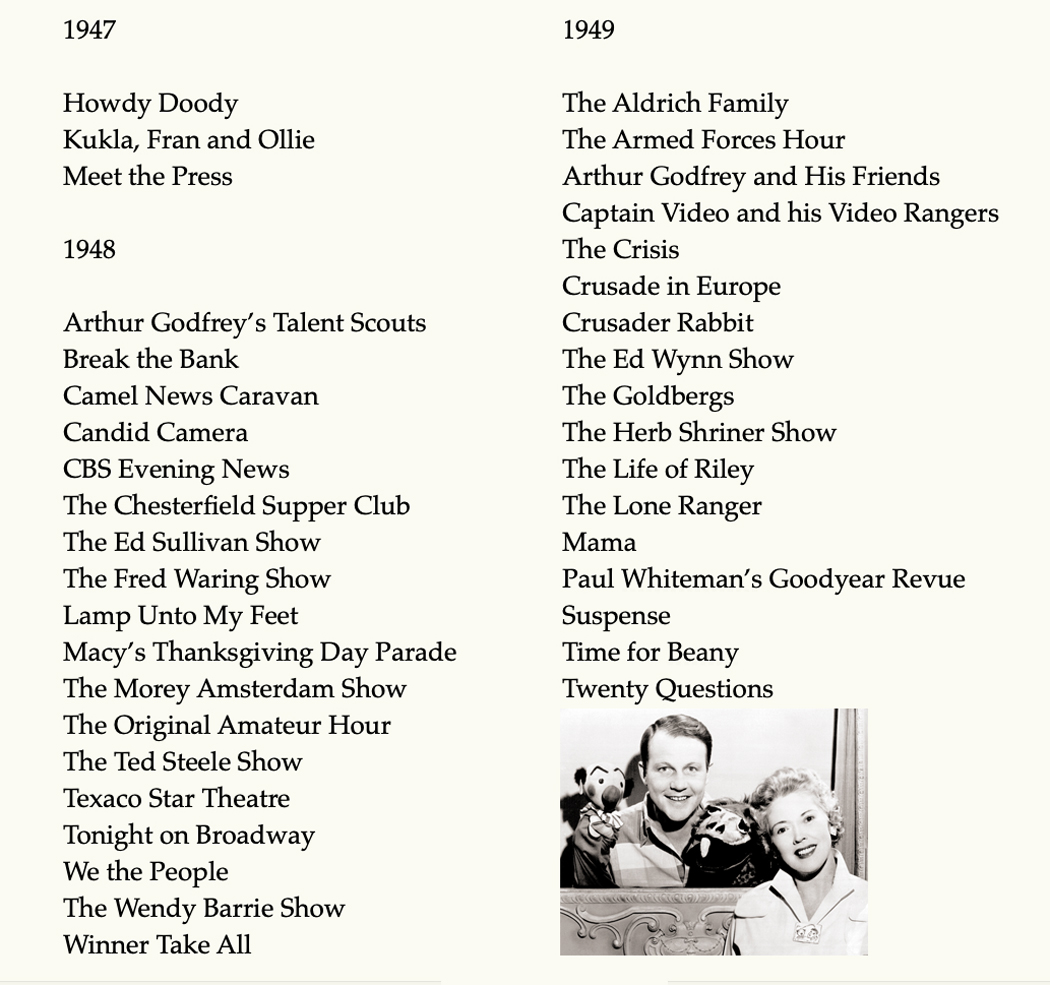

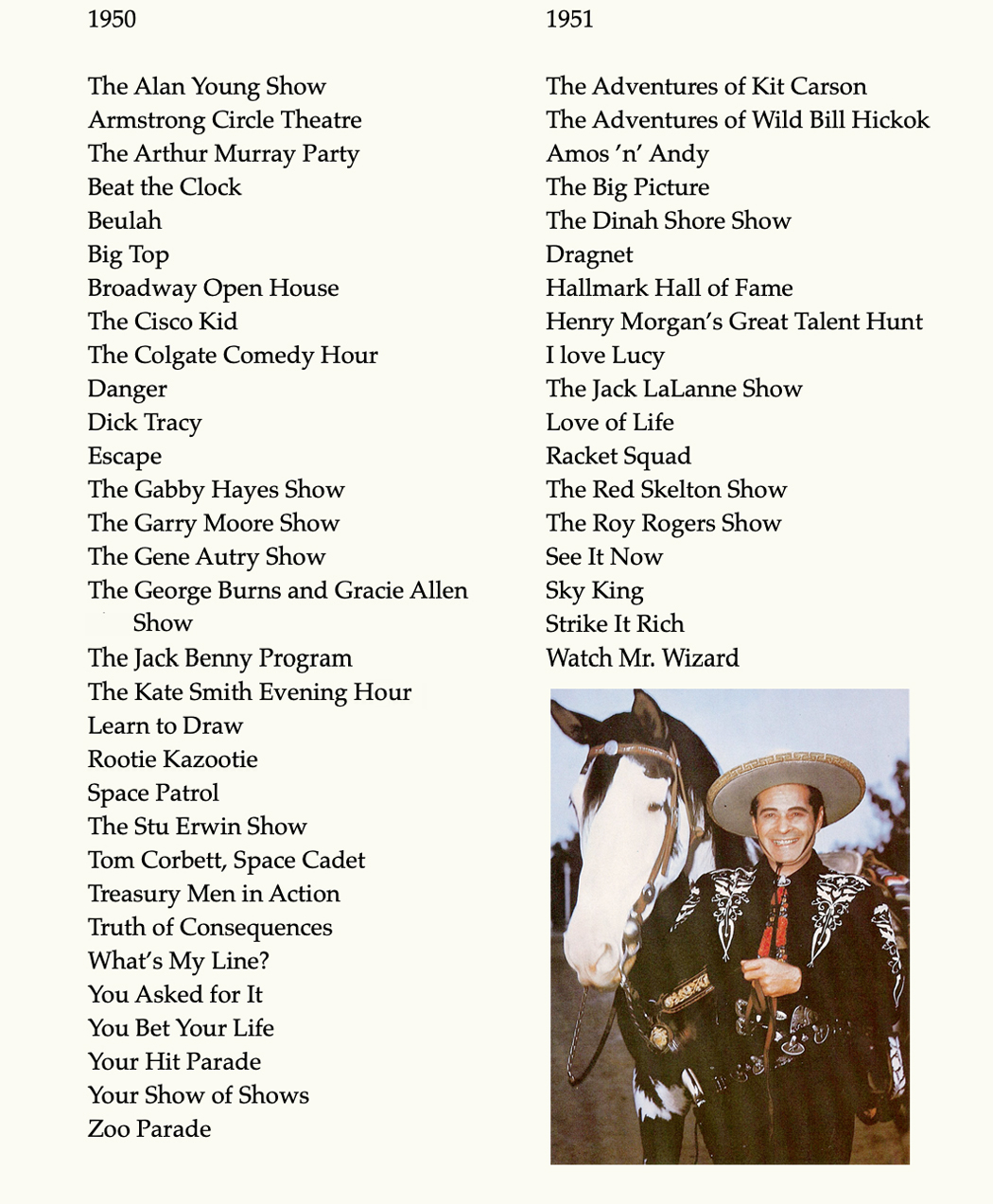

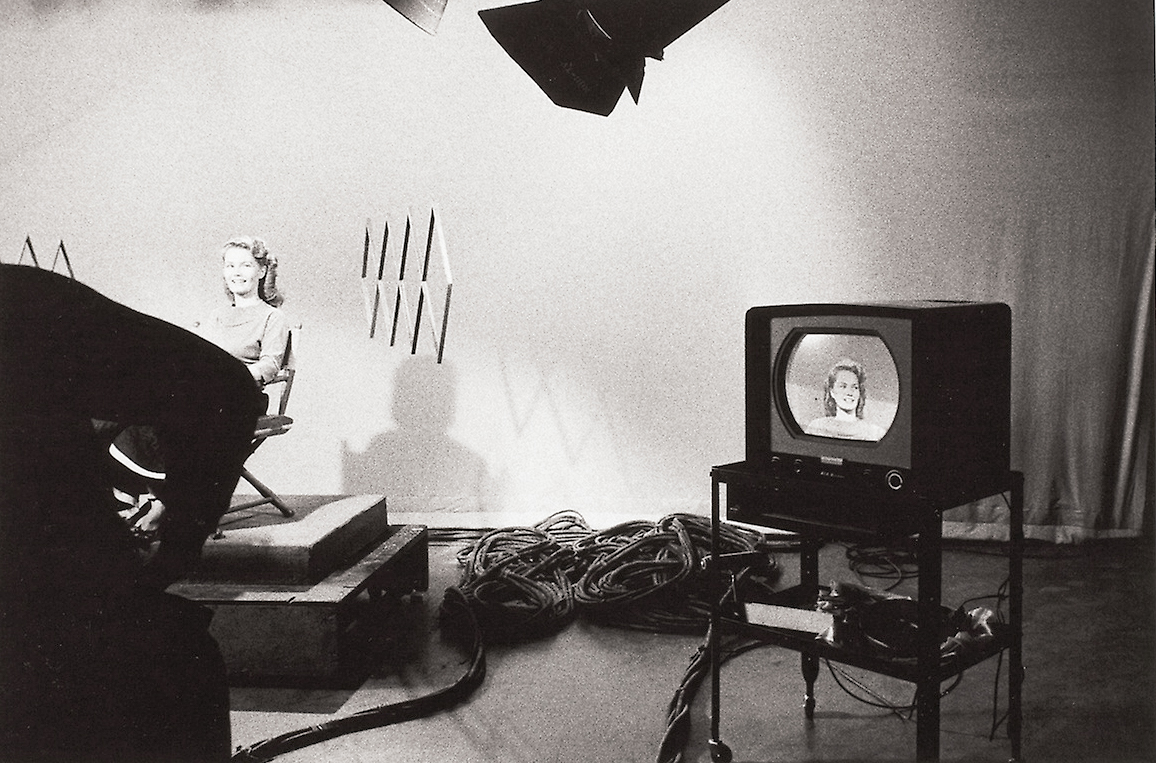

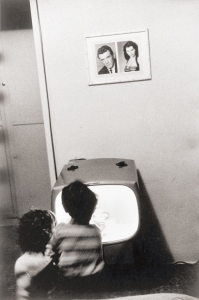

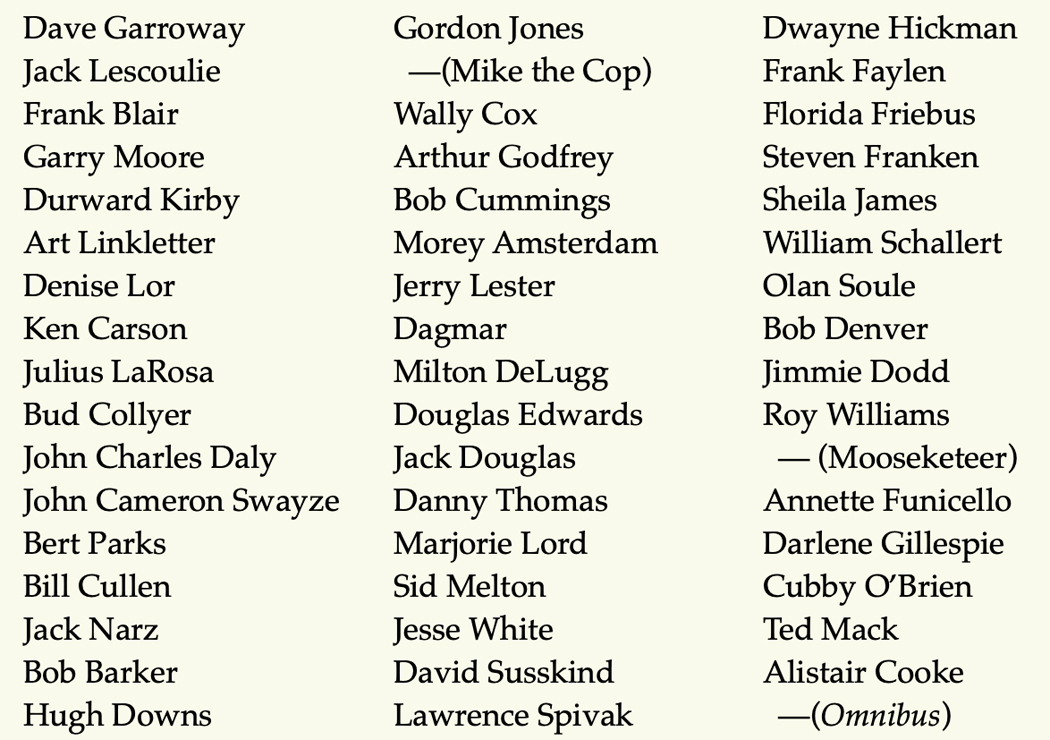

I am roughly the same age as television, and have watched the sitcom from its earliest TV days. I was one year old when The Goldbergs switched from radio to television (“Yoo-Hoo, Mrs. Bloom…”). There was The Aldrich Family from 1949 to 1953 (“Henry! Henry Aldrich!” “Coming, Mother.”), and the first season of The Life of Riley, with Jackie Gleason originally taking over the title role from William Bendix, who had played the part on radio (“What a revoltin’ development this is”). Bendix took back the role for the rest of the series run. I don’t know how old I might have been when I first started watching these series. Probably in my playpen watching the images wiggle on the 12-inch screen of a Dumont television.

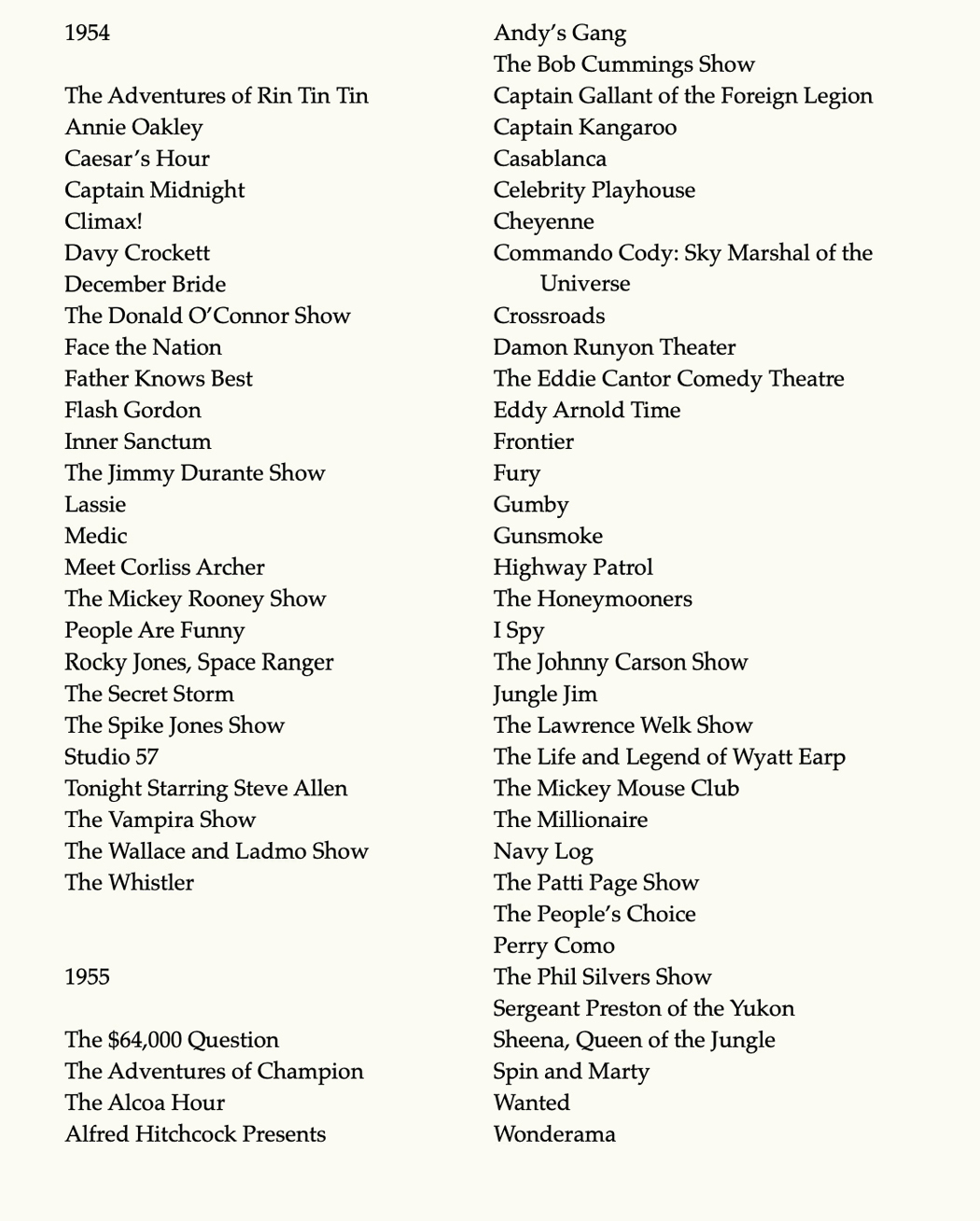

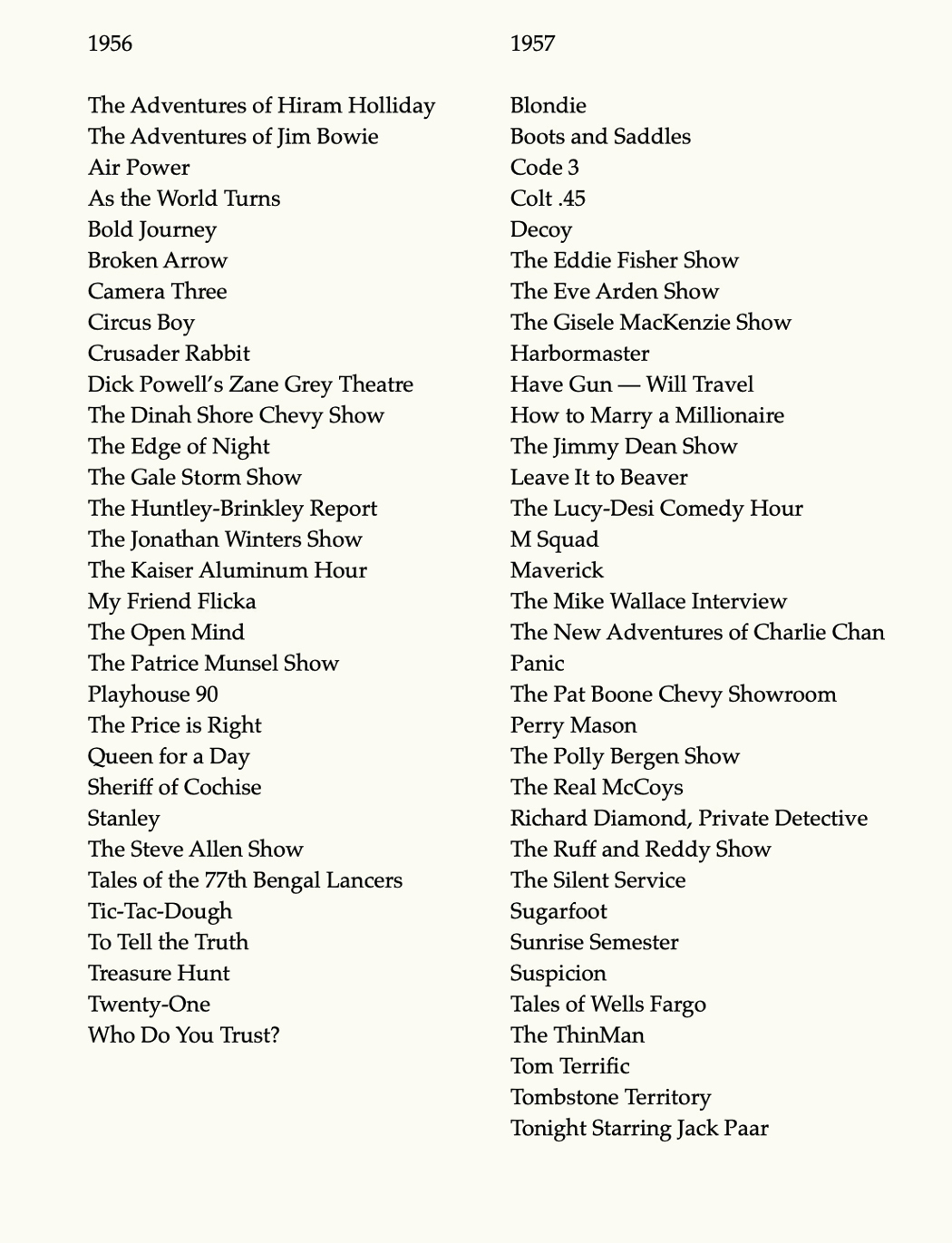

The 1950s brought the onslaught and the sitcom became a staple of the boob tube. These series I remember quite well: Beulah; The Bob Cummings Show; The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show (the first Postmodern show, where George could watch what Gracie was planning on his own TV screen and comment to the audience); December Bride; I Married Joan; Private Secretary; Mister Peepers.

I haven’t mentioned the three most important shows of the time. The Honeymooners emerged as a sometime skit on Cavalcade of Stars, the Jackie Gleason variety show on the Dumont network, sometimes taking up most of the run time. But in 1955, the skit was spun off into a half-hour sitcom for 39 episodes, still run in syndication on various cable channels. (“To the moon, Alice”).

I Love Lucy ran from 1951 to 1957 and pioneered the three-camera filmed sitcom with live audience and laugh track. For its entire run, it ranked No. 1, No. 2, or No. 3 in the ratings. (I have to confess, contrary to the majority opinion, I never found Lucy very funny. Watching reruns, I still don’t). Those reruns can still be found in syndication on cable.

Alvin Childress, Tim Moore, Spencer Williams

But you won’t find Amos ’n’ Andy. It was enormously popular from 1951 to 1953. But reaction to the racial stereotypes changed markedly during the rise of the Civil Rights movement. It would be hard to complain about the series cancellation. In the context of its times, it was deserved. It can be hard to watch nowadays. But I have seen all 78 episodes on bootleg DVDs and must admit we have lost some brilliant comic performances, especially by ex-vaudevillian Tim Moore as the Kingfish. Yes, there are some awful stereotypes, but not everyone was shufflin’ and grifting. Amos was an upright citizen and family man, and the series showed quite a few Black doctors and judges, all horrified at the shenanigans of the series stars.

And it should be pointed out that most sitcoms, Black, white or otherwise, focus on less-than-admirable characters. Let’s face it, bland Ward Cleaver does not support a TV series. You need Archie Bunker, Ralph Kramden, or Larry David. Something out of the norm, but exaggerated. Getting past the particulars of Amos ’n’ Andy, basically the same stereotypes come back later as George Jefferson or J.J. in Good Times (“Dyn-O-Mite”) or Redd Foxx in Sanford and Son. Same caricatures, different generation.

I’m not suggesting we forgive Amos ’n’ Andy, but rather to see it in context, and recognize the talent that went into it.

The fact that even Millennials know who Lucy Ricardo was, or Ralph Kramden or Rob and Laura Petrie, means that some of the hundreds of sitcoms that have aired, from the last century and this, have a cultural staying power, very like the classics we read at university.

The foundational stereotypes — or archetypes — have persisted, too. How many sitcoms feature bumbling husbands, from Chester A. Riley and Ozzie Nelson to Curb Your Enthusiasm and The King of Queens? Conversely, the trope of the ditzy wife, from Gracie Allen to Married … With Children to The Middle? Mothers-in-law are a perennial butt of jokes, as are clueless bosses and gay best friends. They each provide a predictable set of familiar and comfortable jokes. (Although the limits of comfort can and have changed over time: Blonde and Polish jokes haven’t worn as well).

And most of these are just modern changes rung on the characters of the commedia dell’arte. Harlequin, Colombina, Pantalone, Pulcinella, Zanni and the lot. We aren’t looking for fully rounded characters so much as familiar types to build plots and gags around — the “situations” in situation comedies.

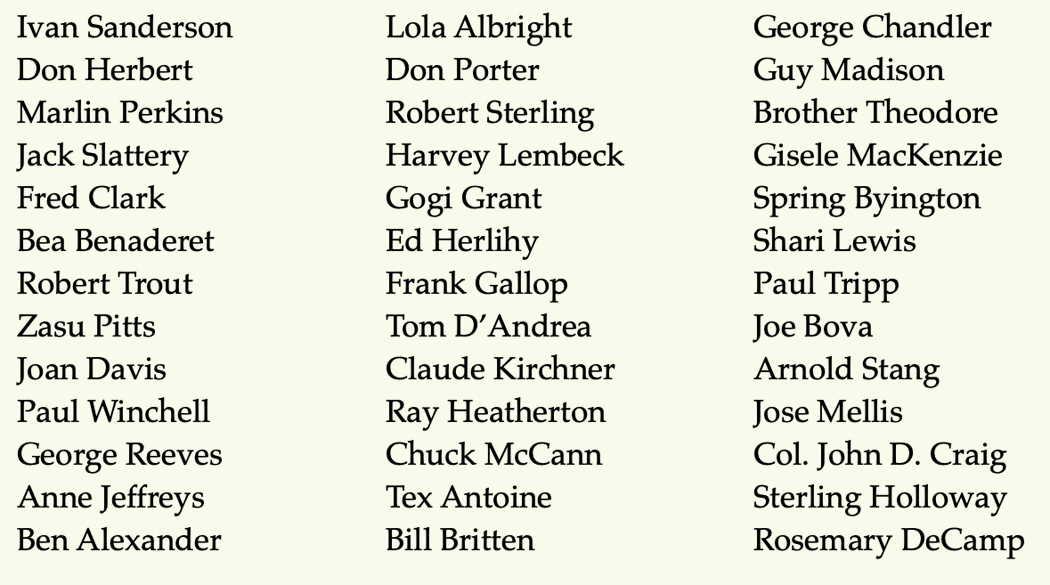

So, the sitcom has a long history. And I have a long history with them. And I have divided them into four roughly defined groups. The borders of these groups may be squishy — you may parse them differently — but the categories are defensible.

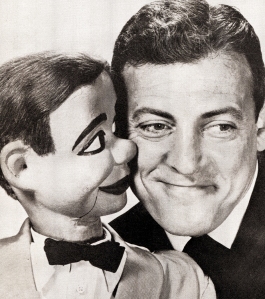

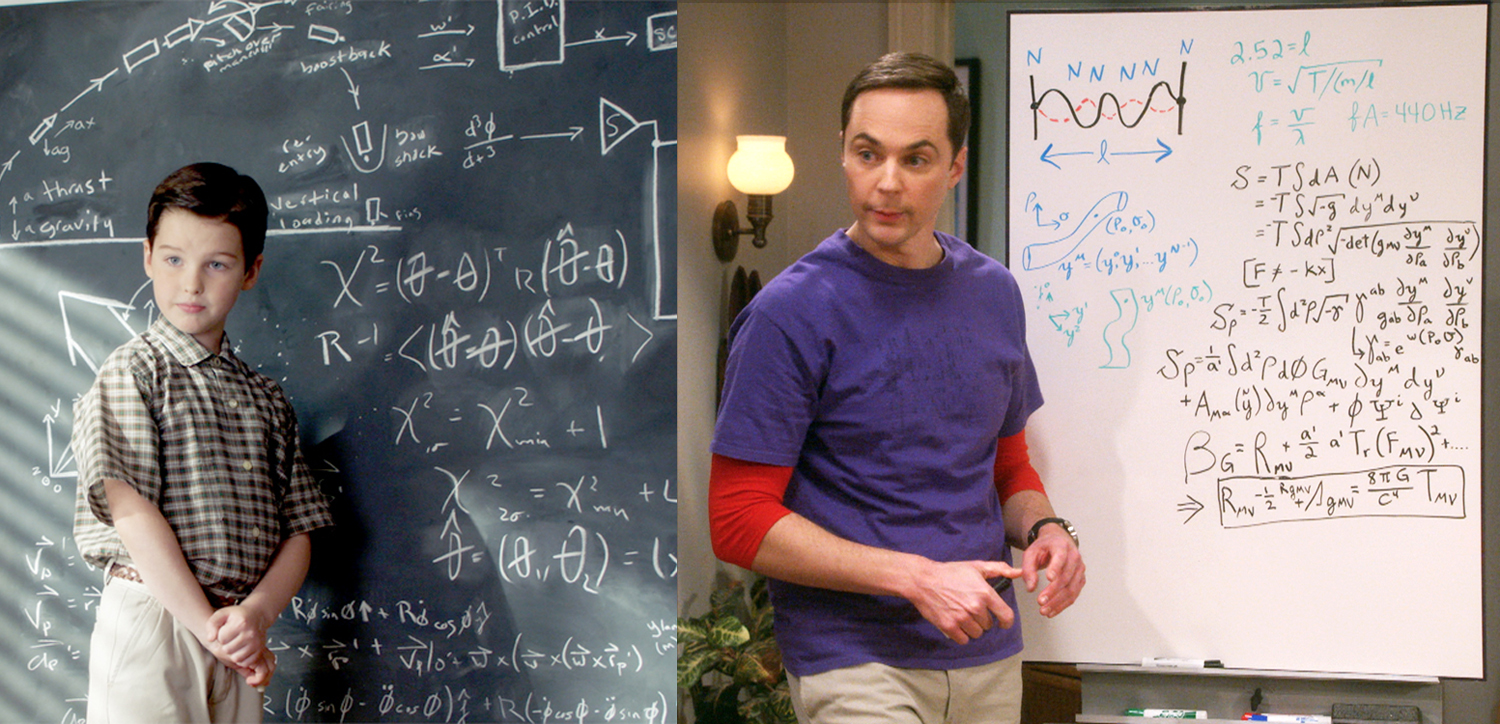

First, there are those that have had an effect on culture broadly. They tend to be the best written and acted, but they have wormed their way into the general consciousness. Class A includes I Love Lucy (my qualms not withstanding), The Honeymooners, All In the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, M*A*S*H, Murphy Brown, The Office (American version), Seinfeld, Roseanne, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and The Cosby Show (which now is hard to watch — both hard to find and hard to endure, knowing what we now know). And I would include both The Big Bang Theory and Young Sheldon. Class acts all the way.

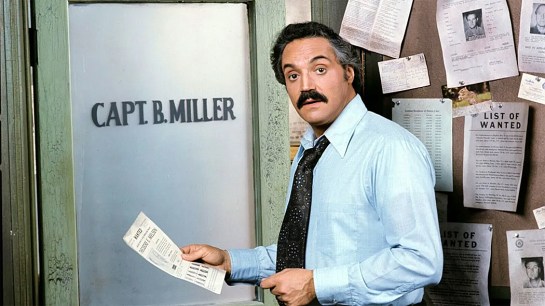

But I would include also: Taxi, Barney Miller, Dick Van Dyke, Cheers, The Bob Newhart Show (the original one), and a few that I never warmed to, but still have a cultural significance, like Friends and Married… With Children. All are or have been in the national conversation.

I should also include a few British series that have had an impact, mainly Fawlty Towers, the British Office, and Absolutely Fabulous.

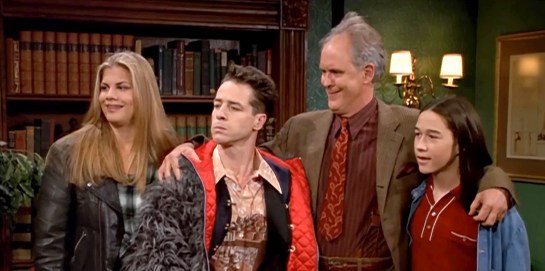

Class B includes all the quality shows that came and went, with funny characters and solid jokes, but never buried into the Zeitgeist in quite the same way. All solid entries. You can add quite a few to this list and it will depend on your taste and funny bone. I would include: 3rd Rock From the Sun; Black-ish; Brooklyn Nine-Nine; Frasier; Golden Girls; The Good Place (should be in Class A, but not enough people watched); Happy Days; Malcolm in the Middle; The Middle; Mike & Molly; Modern Family; The New Adventures of Old Christine; Parks and Recreation; Scrubs; Two and a Half Men; Veep; WKRP in Cincinnati; and your choice of others. Among my favorites are Mom, Night Court, Reno 911. Individual taste may vary. (I have not included many of the old shows from the ’50s and ’60s that few people have had a chance to see: My Little Margie, Private Secretary; Topper.)

The next rung down, in Class C are the workaday shows, sometimes OK time-wasters, but full of cliched characters and tired jokes — the kind that have the familiar form of jokes, but seldom the wit or laughs. Writing on autopilot. This is the vast majority of TV sitcom bulk. The roughage and fiber of the viewing diet.

When we watch these, it is often more out of habit than desire. The forms are familiar and the laugh track tells us when a joke has passed by. Did anyone ever think The Munsters was prime comedy? or Gilligan’s Island? McHale’s Navy? Saved by the Bell? Mediocrity incarnate. Hogan’s Heroes? I could name a hundred, propelled by laugh tracks and the need of writers to fill air time. Networks toss them on the screen, hoping they’ll stick. Some do, but only because they are gluey.

Wikipedia lists hundreds of sitcom titles and I would guess some 75 percent of them fall into Class C. At least half of those are gone in a single season, un-renewed, or cancelled after a few goes. The rest stick around because they are not overly offensive. They may feature actors we like, even if they have to spout insipid dialog.

Bewitched; The Brady Bunch; Chico and the Man; Community; Ellen; F Troop; The Facts of Life; The Flying Nun; I Dream of Jeannie; Last Man Standing; The Monkees; Perfect Strangers; That ’70s Show; Who’s the Boss? Go ahead: Make a case for any of them. Tube fodder.

Three’s Company is the epitome of Class C, although my son, deeply knowledgeable in the ways of film and media, assures me it is a classic. He loves it. De gustibus.

Then, there is the bottom feeding Class D, those shows so bad they have become legend. My Mother the Car is the type specimen for this class. A series only a studio executive high on cocaine and bourbon, and distracted by facing an expensive divorce and maybe a teenage son in jail could have green-lighted. Quite a few of these were meant to be vehicles for aging film stars given their own sitcom series. The Doris Day Show, The Debbie Reynolds Show, The Tammy Grimes Show, Mickey (with Mickey Rooney), The Paul Lynde Show (in which he is an attorney and family man), Wendy and Me (with George Burns and Connie Stevens), Shirley’s World (Shirley MacLaine as a photojournalist), and The Bing Crosby Show. Most of these didn’t make it past the first season.

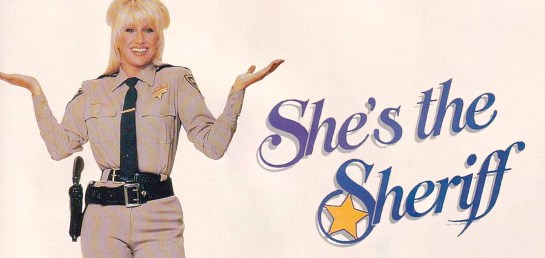

Also at the dismal bottom: Hello Larry, New Monkees, She’s the Sheriff, The Trouble with Larry (“not just not funny, but actively depressing”), Cavemen, Homeboys in Outer Space, The Ropers. Most cancelled after one season.

In England, Heil, Honey, I’m Home with Adolf and Eva never made it past the first episode. (currently unavailable on streaming or disk. Too soon?).

Among the abject failures are most of the American remakes of popular British comedies. Many of them never made it past the pilot stage.

And so, you have four general classes of television sitcoms. The best worthy of saving for future generations, the worst best left for whatever is the digital version of the bottom of the canary cage.

The past wasn’t so different. What we remember of classical Roman comedy are what is extant. Much isn’t. A good deal of it was probably just as banal as most bad TV. We don’t know: It didn’t survive. The Victorian novel was largely a serial enterprise, like seasons of a sitcom, weekly chapters published. But for each Dickens or Trollope, there were dozens, maybe hundreds of lesser works now mostly forgotten. In time, we will no doubt continue winnowing the TV past, saving the Norman Lears and perhaps the Chuck Lorres and ranking them as our Plautus and Terrence. Perhaps.

The low arts can still be art.