When I was a wee lad, in the 1950s and television was about the same age, I watched the images on the screen flash by with no critical eye. It was all the same: old movies, kiddie shows, talk shows, variety shows, sitcoms — it all wiggled on the toob and that was enough.

If there were any difference in production quality, or acting ability, it made no difference. I just watched the story, or listened to the music. The very idea that there were people behind the camera never occurred. I didn’t really even think about there being a camera. Things just appeared. I suspect this is true for most kids. It may be true for quite a few grown-ups, too.

There were certainly programs I liked more than others, but I could not have given any reason why one and not the other. Mostly, in the daytime, I watched cowboy movies and cartoons, and in the evening, I watched whatever the rest of the family was watching.

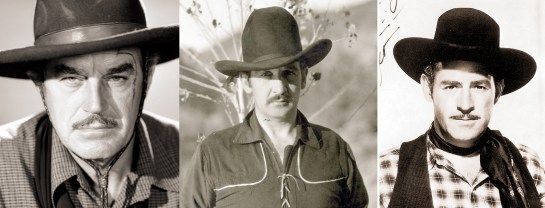

In all that, there were a good number of Westerns. There were those for the kids, such as The Lone Ranger or The Cisco Kid, and later, those in the after-dinner hours aimed at the grown-ups — Gunsmoke or Death Valley Days. There were also the daytime screenings of old Western movies with such stars as Buck Jones, Hoot Gibson, Bob Steele or Johnny Mack Brown.

I mention all this because I have recently begun watching a series of reruns of old TV Westerns on various high-number cable channels, seeing them in Hi-Def for the first time. I have now seen scores of original Gunsmoke episodes and my take on them is entirely different from when I was in grammar school. I can now watch them critically.

It’s been 70 years since I was that little kid, and since then I’ve seen thousands of movies and TV shows, served a stint as a film critic, written about movies, and introduced films in theaters. I have a different eye, and understand things I couldn’t know then.

And so, a number of random thoughts have come to me, in no particular order:

1.

Old TVs were fuzzy; new TVs are sharp. In the old days of cathode-ray tubes, TV pictures were made up of roughly 480 lines, running from top to bottom of the screen, refreshing themselves every 60th of a second. Broadcast TV was governed by what is called NTSC standards (altered slightly over time). Such images were of surprisingly low definition (by modern standards).

The sharpness of those early TV pictures was not of major importance because most people then really thought of television as radio with pictures, and story lines were carried almost entirely by dialog. The visual aspect of them was of minor concern (nor, given the resolution of the TVs at the time, should it have been.)

Of course, now, we watch those old Gunsmoke episodes on HD screens. And two things become apparent.

First, is that shows such as Gunsmoke were made better than they needed to be. They were made mainly by people trained in the old Hollywood studio system, where such things as lighting, blocking, focus, camera angles, and the such were all worked out and professionally understood. They were skilled craftsmen.

However, second, some things were designed for analog screens, and so, often, painted backdrops used, especially for “outdoor” scenes shot in the studio, have become embarrassingly obvious, when, originally, they would have passed unnoticed on the fuzzy screen.

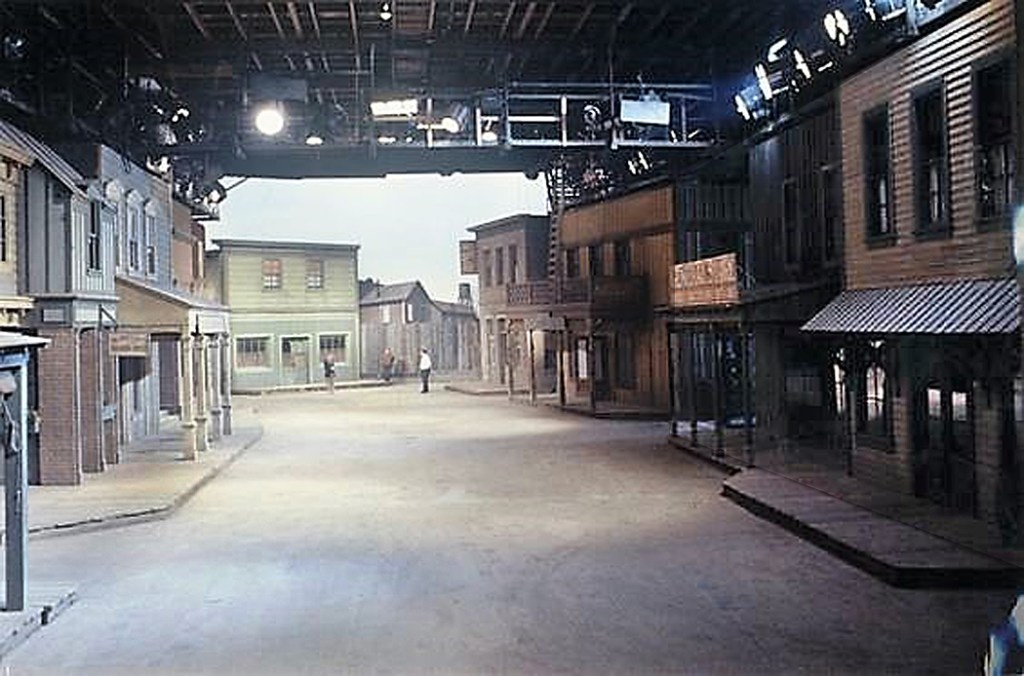

Outdoor scenes were often shot in studios. Dodge City, during some seasons, was built indoors and the end of the main street in town was a backdrop. Again, on the old TVs you would not notice, but today, it’s embarrassing how crude that cheat was.

You can see it in the opening shootout during the credits. In early seasons, Dillon faces the bad guy outdoors. In later seasons, he’s in the studio.

2.

Because Gunsmoke is now seen on a widescreen HD screen, but were originally shot for the squarer 4-by-5 aspect ratio, the image has to be rejiggered for the new screen. There are three ways of doing this, and as they show up on current screens, they are either shown with black bars on either side of the picture, to retain the original aspect ratio, or they are cropped and spread out across the wider 16:9 space. And if so, there are two ways this happens.

If the transfer is done quickly and cheaply, the cropping is done by just chopping off a bit of the top and bottom of the picture, leaving the middle unchanged. The problem is this often leaves the picture awkwardly framed, with, in close ups, the bottoms of characters’ faces left out.

However, in some of the newly broadcast Gunsmokes, someone has taken care to reframe the shots — moving the frame up or down — so as to include the chins and mouths of the characters. To do this, the technician has to pay attention shot by shot as he reframes the image.

And so, it seems as if the Gunsmoke syndications have been accomplished either by separate companies, or at different times for different series packages. You can see, for instance, on the INSP cable network, examples of all three strategies. (My preference, by far, is for the uncropped original squarer picture.)

3.

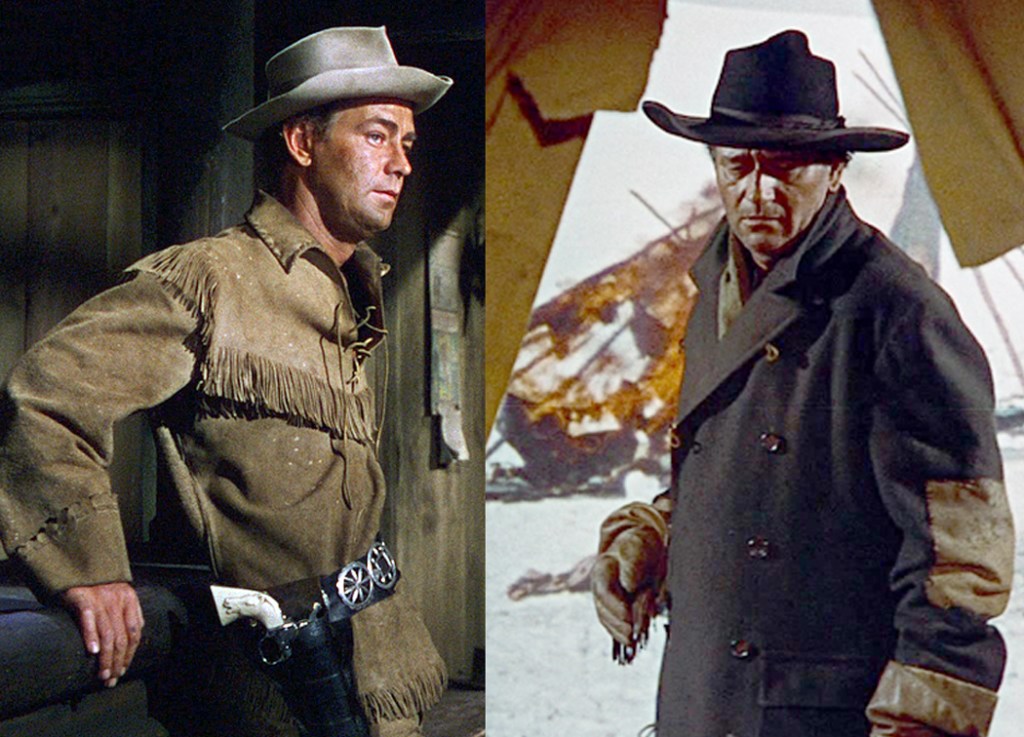

Gunsmoke changed over its 20-year TV run. There are three main versions: Black and white half-hour episodes (1955-1961); black and white hour-long episodes (1961-1966); and hour-long color episodes (1966-1975). The shorter run times coincided with the period when Dennis Weaver played Matt Dillon’s gimpy-legged sidekick Chester Goode. Chester continued for a season into the hour-longs, but was replaced by Ken Curtis as Festus Haggen, the illiterate countrified comic relief.

Technically, the black and white seasons were generally better made than the color ones. When the series began, TV crews had been those previously at work in cinema, and brought over what they learned about lighting, framing, editing, blocking, use of close-ups. The black and white film stock allowed them to use lighting creatively, using shadows to effect, and lighting faces, especially in night scenes, with expressive shadows. Looking at the older episodes, I often admire the artistry of the lighting.

But when color came in, the film stock was rather less sensitive than the black and white, and so the sets had to be flooded with light generally for details to be rendered. This led to really crass generic lighting. Often — and you can really spot it in night scenes — a character will throw two or three shadows behind him from lights blasting in different directions. Practicality drowns artistry.

Gunsmoke wasn’t alone in this: This bland lighting affected all TV shows when color became normal. It took decades — and better film stock — before color lighting caught up. (One of the hallmarks of our current “golden age” of TV is the cinematic style of lighting that is now fashionable. Color has finally caught up with black and white.)

4.

One of the pleasures of watching these reruns is now noticing (I didn’t when I was a little boy) the repertory company of actors who showed up over and over again, playing different characters each time.

I’m not just talking about the regular actors playing recurring roles, such as Glenn Strange as Sam the barkeep or Howard Culver, who was hotel clerk Howard Uzzell in 44 episodes, but those coming back over and over in different roles. Victor French was seen 18 times, Roy Barcroft (longtime B-Western baddie) 16 times; Denver Pyle 14 times, Royal Dano 13 times, John Dehner, John Anderson and Harry Carey Jr. a dozen times each.

Other regulars with familiar faces include Strother Martin, Warren Oates, Claude Akins, Gene Evans, Harry Dean Stanton, Jack Elam. Some were established movie actors: George Kennedy, Dub Taylor, Pat Hingle, Forrest Tucker, Slim Pickens, Elisha Cook Jr., James Whitmore. Bette Davis, too.

William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, DeForest Kelley, James Doohan

And a few surprises. Who knew that Leonard Nimoy was in Gunsmoke (four times), or Mayberry’s George Lindsay (six times — usually playing heavies and you realize that the goofy Goober Pyle was an act — Lindsay was an actor, not an idiot), Mayberry’s barber Howard McNear showed up 6 times. Jon Voight, Carroll O’Connor, Ed Asner, Harrison Ford, Kurt Russell, Suzanne Pleshette, Jean Arthur, DeForest Kelley, Werner Klemperer (Colonel Klink), Angie Dickenson, Dennis Hopper, Leslie Nielsen, Dyan Cannon, Adam West, and even William Shatner — all show up.

It becomes an actor-spotting game. John Dehner, in particular, was so very different each time he showed up, once a grizzled old miner, another a town drunk, a third as an East-coast dandy, another as a hired gunslinger — almost never looking or sounding the same. “There he is, Dehner again!”

And it makes you realize that these were all working actors, needing to string together gigs to make a living, and the reliable actors would get many call-backs. It is now a pleasure to see how good so many of these old character actors were.

5.

I have now watched not only Gunsmoke, but other old TV Westerns, and the quality difference between the best Gunsmoke episodes and the general run of shows is distinct. While I have come to recognize the quality that went into the production of Gunsmoke, most of the other shows, such as Bonanza, simply do not hold up. They are so much more formulaic, cheaply produced, and flat. Stock characters and recycled plots.

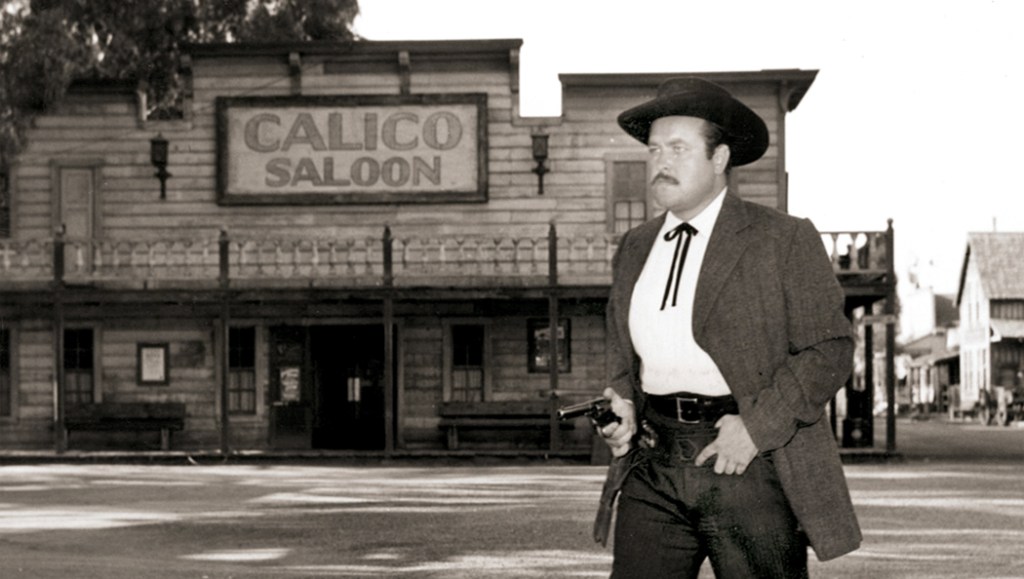

Gunsmoke was designed to be an “adult Western” when it was first broadcast, in 1952, as a radio show, with stocky actor William Conrad as Matt Dillon. In contrast to the kiddie Westerns of the time, it aimed to bring realism to the genre.

William Conrad as Marshal Dillon

It ran on radio from ’52 to 1961, and on TV from 1955 to 1975, and then continued for five made-for-TV movies following Dillon in his later years. There were comic books and novelizations. Dillon became a household name.

Originally, Matt Dillon was a hard-edged, lonely man in a hard Western landscape. As imagined by writer and co-creator of the series John Meston, the series would overturn the cliches of sentimental Westerns and expose how brutal the Old West was in reality. Many episodes were based on man’s cruelty to both men and women. Meston wrote, “Dillon was almost as scarred as the homicidal psychopaths to drifted into Dodge from all directions.”

On TV, the series mellowed quite a bit, and James Arness was more solid hero than the radio Dillon. But there was still an edge to the show, compared with other TV Westerns. After all, according to True West magazine, Matt Dillon killed 407 people over the course of the TV series and movie sequels. He was also shot at least 56 times, knocked unconscious 29 times, stabbed three times and poisoned once.

And the TV show could be surprisingly frank about the prairie woman’s life and the painful treatment of women as chattels.

In Season 3 of the TV series, an episode titled “The Cabin,” two brutal men (Claude Akins and Harry Dean Stanton) kill a woman’s father and then serially beat and rape her over the course of 35 days, when Dillon accidentally comes upon the cabin to escape a snowstorm. The thugs plan to kill the marshal, but he winds up getting them first. When Dillon suggests that the woman can now go back to living her life, the shame she feels will not let her. No one has to know what has happened here, he tells her, but, she says, she will know. And so she tells Dillon she will go to Hayes City, “buy some pretty clothes” and become a prostitute. “It won’t be too hard, not after all this,” she says.

“Don’t let all this make you bitter,” Dillon says. “There are a lot of good men in this world.”

“So they say” she says.

This is pretty strong stuff for network TV in 1958. There were other episodes about racism, and especially in the early years, not always happy endings.

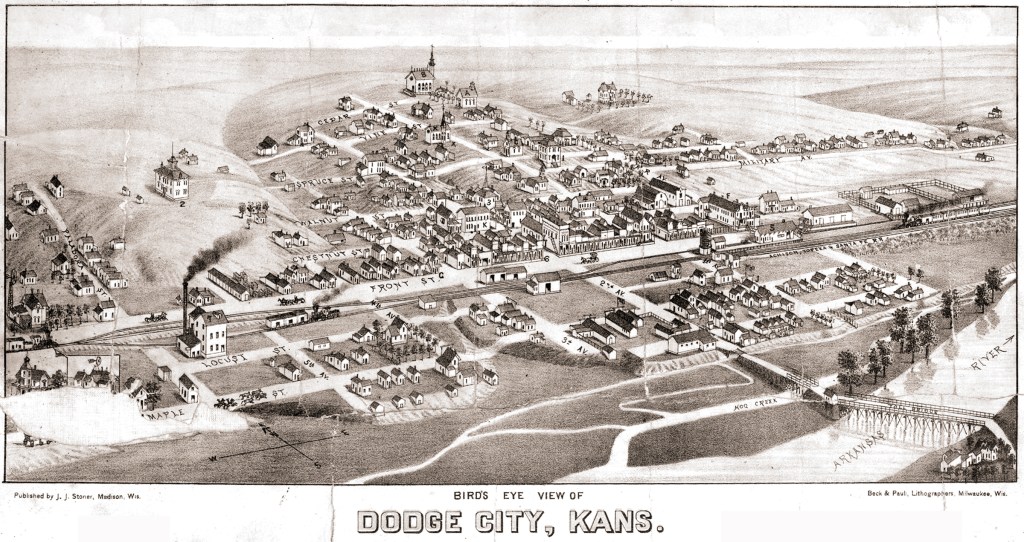

Dodge City, 1872

6.

According to Gunsmoke producer John Mantley, the series was set arbitrarily in 1873 and in Dodge City, Kansas, on the banks of the Arkansas River, although the river plays scant role in the series. In 1873, the railroad had just arrived, although in only a few episodes of the TV series is the train even mentioned.

The Dodge City of the series is really just a standard Hollywood Western town, with the usual single dusty street with wooden false-front buildings along either side.

In reality (not that it matters much for a TV show, although Gunsmoke did try to be more realistic than the standard Western), Dodge was built, like most Southern and Western towns, with its buildings all on one side of the street (called Front Street in Dodge) and the railroad tracks on the other. Beyond that, the river.

Dodge City, Kansas 1888

And in general, the geography of Gunsmoke’s Kansas would come as a surprise to anyone visiting the actual city. The state is famously flat, while the scenery around Matt Dillon often has snow-capped mountains, and at other times, mesas and buttes of the desert Southwest.

Hollywood’s sense of geography is often peculiar. So, I don’t think it is fair to hold it against the TV series that its sense of the landscape has more to do with California (where the series was generally shot) than with the Midwest prairies.

I remember one movie where James Stewart travels from Lordsburg, N.M., to Tucson, Ariz., and somehow manages to pass through the red rocks or Sedona on the way. Sedona is certainly more picturesque than Wilcox, Ariz., but rather misplaced.

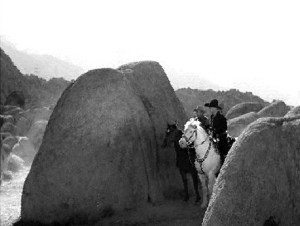

Or John Ford’s The Searchers, where the Jorgensen and Edwards families are farming in Monument Valley, Ariz., which has no water, little rain, sandy soil and no towns within a hundred miles. It is ludicrous place to attempt to farm. Of course, it is said, in the movie, to be set in Texas, but Texas doesn’t look like the Colorado Plateau at all.

We forgive such gaffes because the scenery is so gorgeous, and because we’ve been trained by decades of cowboy movies to have a picture of “The West” as it is seen in Shane rather than how most of it actually was: flat, grassy, and boring. And often, it is not even the West, as we think of it. Jesse James and his gang robbed banks in Missouri. The Dalton Gang was finished off in Minnesota. The “hanging judge” Parker presided in Arkansas. Some of the quintessential Western myths are really Midwestern or Southern.

So, many of the tropes of Hollywood Westerns still show up in Gunsmoke, despite its attempt at being “more realistic” than the standard-issue cowboy show.

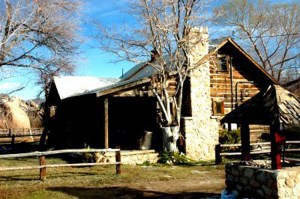

“Gunsmoke” studio set

Two things, however, that are hardly ever mentioned that seems germane to the question of realism on film. The first is the pristine nature of the streets. Historians have shown that, with all the horses, not only in Westerns, but even in 19th-century Manhattan, the streets were paved with horseshit. Cities even hired sanitation workers to collect the dung in wheeled bins, so as not to be buried in the stuff.

OK, I get that perhaps on TV shows broadcast into our homes, we might not want to see that much horse manure. In reality, the dirt dumped in the studio set of Dodge City had to be cleaned out, like kitty litter, each day, or under the hot lights, the whole set would stink of horse urine.

But the second issue relates to the very title of the show: Gunsmoke. Strangely, smoke never appears from the many guns being fired in the course of 20 years of episodes. But the series is set in an era at least a decade before the invention of a practical smokeless powder (and 30 years before its widespread usage). And so Matt Dillon’s gun should be spouting a haze of nasty smoke each time he fires at a miscreant.

Me firing a black powder rifle

We know, from records of the time, that Civil War battlefields, and before that, Napoleonic battlefields, were obscured by clouds of impenetrable smoke, blocking the views of soldiers aiming at each other. And I know from my own experience firing black powder weapons, that each show spews a cloud of smoke from the barrel. So, why no gun smoke on Gunsmoke?

Click on any image to enlarge