Over the past dozen years, since my retirement, I have written and posted some 730 blog entries. But I have started many more than that. Some just get forgotten when something more urgent appears; some end short because nothing longer needs to be said. Some just led nowhere. Others began as lists, but ended as lists, unfilled by full sentences. And still more still wait to be written.

The odd thing, to me, is that there is always something new to write about. With 75 years of life packed into this aging piece of meat, there are endless stories, bits, adventures, ideas, experiences, disappointments and discoveries to draw upon. The well keeps refilling.

But here are a few fragments that never filled out beyond their early inspiration. Maybe I will get around to it, sometime.

What is it that women see in men? Because I am a man, I know what men see in women, but I have a hard time reversing the equation.

I am not here talking of sex or the ardor of the loins — understanding is not required for that; it is simple, direct action — but the desire of women to share company with men. What is the reward for that? Women are so much more interesting, and interested in such a variety of vital issues. Men seem interested only in sports and politics, neither of which carry much import in the lives we live. As I used to say, “Politics answers no question worth asking.”

____________

2. I was a writer for many years, making my living from putting words against words, hoping to find the best way to express something I hoped would be genuine.

Recently, my old employer, Gannett, made a new hire, and announced it in such a clot of management-buzz that I got a bad case of hiccups. Newspapers used to have editors, now, with middle management bloated beyond belief, while laying off reporters, photographers and copy editors, what they have is a “Chief Content Officer.”

The announcement came with a gnat-swarm of buzz words, which may mean something to other management types, but not anything penetrable by actual human beings:

“ ‘We are thrilled to welcome Kristin to Team Gannett to champion innovative storytelling opportunities and develop strategic content initiatives to expand our audience and drive growth,’ Reed said in a Monday news release.”

“Strategic content initiatives?” You would think that those people who run a newspaper would have some sensitivity to language. If I had written prose like that, I would have been out of a job.

3. The glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome. Or maybe not so much.

We owe a great deal to ancient Greece. At least, we pay lip service to our debt of democracy, philosophy, literature, science and not least, saving European culture from being overrun by that of Persia. But there are a host of words that describe the part of ancient Greece we would rather forget: Misogyny, xenophobia, pedophilia — come to us dressed in Greek etymology, and descend to us from Greek ideas and practice. We need to address some of the less attractive legacies of that Golden Age.

Such as patriarchy, idealism, imperialism, colonialism, religious intolerance, cults, ethnocentrism, slavery. To say nothing of understanding sex as an exercise in dominance. And while we may think of Plato as the source of all philosophy, remember that he despised democracy and was an ardent believer in totalitarianism.

____________

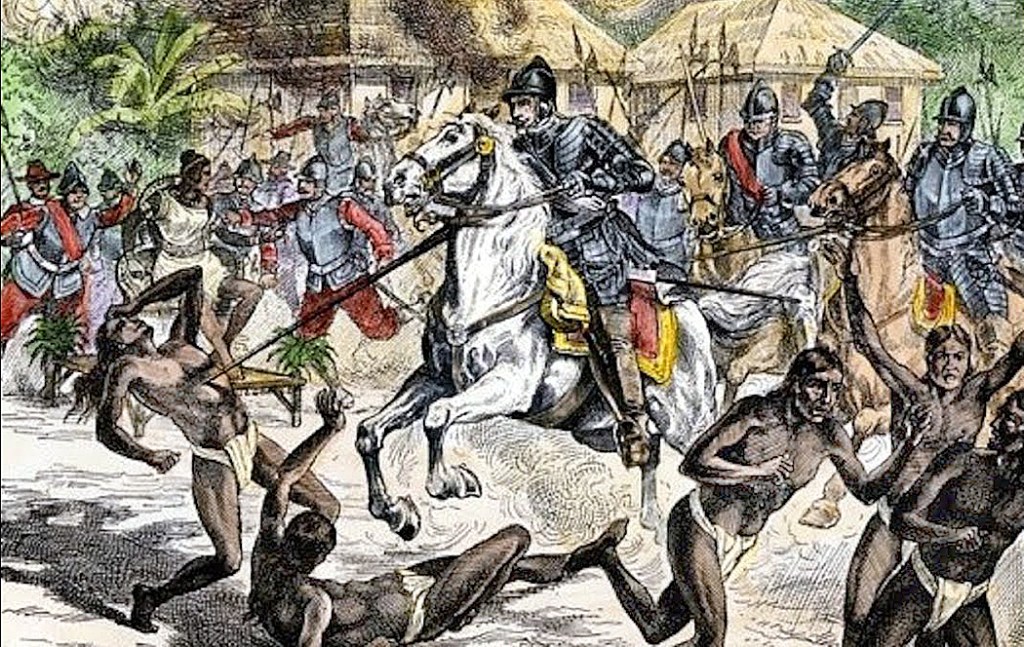

4. Columbus Day is a month away. I expect more anti-Columbus newspaper columns, art, a few tracts and manifestoes and perhaps a new opera. Much current art that tries to be political is really just polemical. To espouse any ideology is to strip life of its complexity. Yes, Columbus was a bad man and the evils he brought with him are real. But instead of preaching to us self-righteously, there are real problems to be discussed, such questions as, “What is in the nature of humans that causes territorial expansion, that causes them to make invisible the people they subjugate, that causes them to divide the world into Them and Us? Why does the boundary of ‘us’ expand and shrink periodically? Why is a world once headed in the direction of one-world nationhood, where the ‘tribe’ is humanity — why is that world now constricting so that nationhood is more tightly defined by blood, so that Serb kills Croat, Azerbaijani kills Armenian? The ethnic separatism that is emerging worldwide is, I believe, a source of exactly the same intolerance that the European West has for so many centuries visited on the rest of the world. Will it devolve to the point that Chiricahua despises Mescalero, or Venetian rises to kill Neopolitan? At what point does a coalition of interests grow from our recognition of our shared humanity?”

Questions such as these are avoided by nearly all political diatribes, whose authors prefer to point fingers and whine like grade-school tattle-tales. If a short perusal of the history of the world teaches us anything, it teaches us that war, inhumanity, violence, intolerance are universal. It isn’t only the Hebrews with their God-ordained genocide of Moabites and Amonites; it isn’t only the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia; it isn’t only Hitler killing Jews and homosexuals; it isn’t only Japan subjugating Manchuria; it isn’t only Custer at Sand Creek; it isn’t only the Hopi at Awatovi.

No one gets off the hook. Native Americans are no more righteous in this than anyone else, from Inca to Aztec to Lakota. If artists and writers chose to look a little closer, they could use Columbus as a metaphor for something richer, profounder, truer. They could have seen that Columbus was not sui generis, but rather representative of the species.

As it is, they came off sounding self-righteous. And no one self-righteous ever has much self-knowledge.

____________

5. Stasis is the enemy. Or rather, because stasis is utterly impossible, the idea of stasis is the enemy. It is the fatal stumbling block of every religion, political philosophy and marriage that has ever existed. Over and over, hundreds, thousands, millions of people die because someone promised them that if we only do things my way, everything will be forever hunky peachy.

It is the lie behind the “original intent” argument espoused by some Supreme Court justices, and behind the infantile promises of politicians — most on the right, these days — that their policies will “finally” fix things and make them good forever. (In the past, it was the left and Marxism that promised a final end of historical change. It is not the sides one takes, but the phantom of permanence).

The problem is that stasis is always temporary, which makes it not stasis. I.e., stasis is a pipe dream.

____________

6. In America, “no” has become a dirty word. Americans like the positive attitude, the gung-ho approach to things. We feel actual moral disapproval of the word “no.”

It can make your life easier and simpler. It can shake a load of guilt off your back. Although people talk of simplifying their lives, you can never simplify by doing something, you can simplify only by not doing something. Just say no. It is the yang to “yes’s” yin, and the universe cannot function without both.

“Yes” is kind of namby-pamby. “Yes” doesn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings. “Yes” is go-along to get along.

“No” is emphatic, direct, take-no-prisoners. “No” means no. Every change and improvement in life, every revolution begins with a “no.”

In some way, every important historical development starts with somebody or some group saying no. Dissatisfaction, after all, is the great inspirer of humanity. If we were all duck happy all the time, nothing would ever get done.

7. I am 75 and am near death (Oh, I’m generally fine, but old and weak) and I think about non-being quite a lot, but not with fear, but a kind of objective interest in the whole idea of no longer hearing birds or feeling the breeze on my skin. Death seems to me a natural “rounding off” of a life and not something that I need to hold in my mouth like a tough crust of bread.

I saw Carole take her last breath. I felt her turn instantly cool to my touch, like I was touching unfired clay. She ceased being. It was uncanny. My grief was incalculable — and it still is, although worn down — but it felt as inevitable or as natural as the coming of winter. I know the same awaits me — “To die — to sleep no more.” No dreams. Nothing.

I didn’t sense a spirit or soul leaving her body, just her body ceasing to produce her being, like a light bulb blown out. We don’t ask a burnt-out lightbulb “where did the light go?” It ceases being generated.

____________

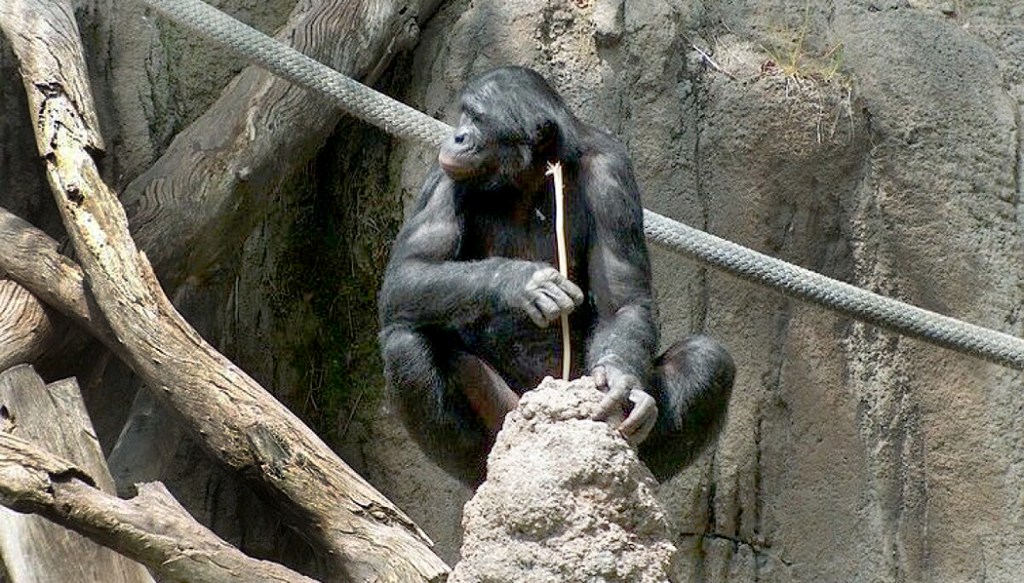

8. One of my problems with Rilke is that I have no use for categorizing angels and animals. Angels don’t exist — not even as metaphors for me — and I accept that I, as a human being, am an animal. I am not so fast to accept that no animals know they are going to die. We have no evidence for that assumption. Perhaps they do; perhaps they don’t. I suspect that some, such as porpoises or whales, may very well have some concept of death. I remember when we human beings were so sure that what separated us from the beasts was tool-making. Ah, but then we discovered how many other animals forge tools.

9. It has seemed to me that part of the German soul is to speak in general and categorical terms, in ideas, rather than in things. It leads to mistaking words for reality. Logic has its own logic, but it is not the logic of the world. (Whole rafts of philosophy, including my hated Plato, only seem to work in words. You can prove with logic that Achilles can never catch the tortoise, but that ain’t how it works in reality.)

But I fear that they are much more about language than about experience. And that is my problem in a nutshell. I made my living with language, and I love words to distraction, but the older I get the more I am convinced that language is merely a parallel universe, with an order and meaning of its own, roughly mirroring the world, but never actually connecting, never touching the pulse of reality. I know, it’s all we have, but I still counsel wariness.

10. “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” Why write at all? It is a question I have wrestled with all my life. Do I have anything worth saying to be value to anyone else? Dr. Johnson said that “nobody but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.” Well, I’m a blockhead: I no longer get paid to string words together. But it doesn’t seem to come as a choice. Some may choose to write; I write with the same volition as I breathe.

Early in my life, words were thin and sparse; it seemed as if there were a lack of hydrostatic pressure from within: I needed to fill myself first. But after living a certain time, the inside pressure grew and it had to come out. It became a fountain I could not stop if I had wanted to. And the well was constantly recharged.

Now I am old, and travel becomes difficult, habits become settled, reading more and more becomes re-reading. In retirement I can no longer afford to attend concerts, plays and dance the way I used to. The incoming has slowed, and I suppose the outflow has dwindled in response, but the backpressure is still there. Hoping to cease not till death.