I was a man with a price on his head.

Granted, it was only a nickel a day, but it was increasing. By the time the Library Police knocked on my door, that price was in the high single dollar range. Who knew the library had police? They came in pairs, like Mormon missionaries, and were nearly as polite; they wanted the money and they wanted their book back. I had forgotten I had even borrowed it from the Virginia Beach Public Library and now, I didn’t know where it was, in the welter of books in the house; I paid them the price of the book to be done with it. This was the most dire episode in my long relationship with libraries.

It was also a long time ago (you should have been tipped off by the fine of a nickel-a-day — library fines have grown with inflation), and it was at a time when I was suffering from student poverty, and so libraries were a godsend when I needed or wanted a certain book — and for those of us with the book affliction, the difference between want and need is very thinly sliced.

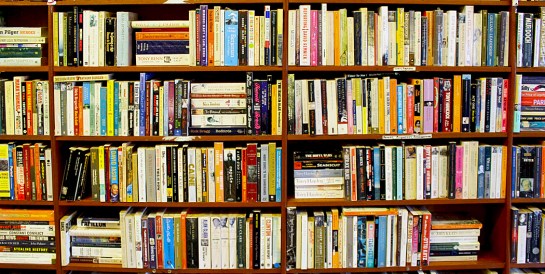

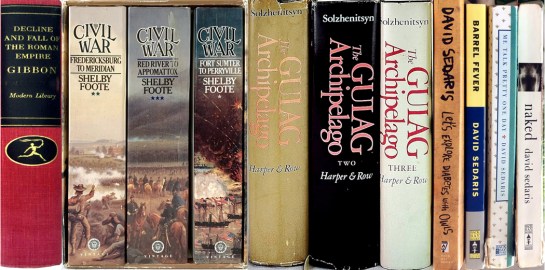

There is a word for this affliction. At first, I just thought of myself as a bibliophile, but the proprietor of a used bookstore in Norfolk, Va., recognizing the symptoms explained to me that what I was, in actuality, was a bibliopath. I kind of liked the name and have perpetuated the usage ever since. You know you are a bibliopath if you have ever feared for the life of your cat when the pile of books on the floor next to your bed reaches critical mass and you suffer what in our household we call a “bookslide.” Buried under there, like survivors of a third-world earthquake, is the unhappy cat you have to exhume.

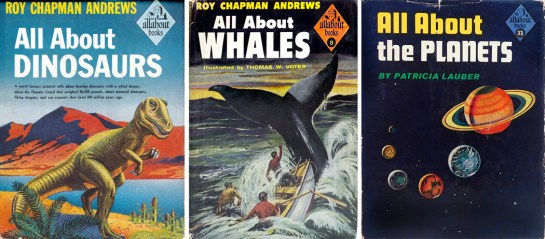

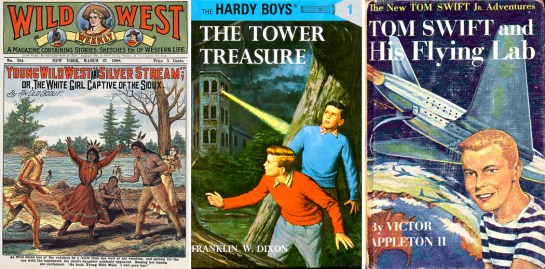

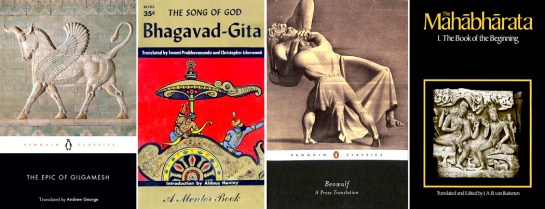

Some of my earliest memories were of descending to the basement of my elementary school in New Jersey, where the town’s public library was hidden, and spending countless hours of joy poring over the shelves and finding the books that would explain the world to me.

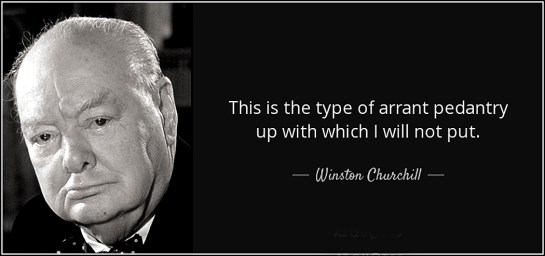

In high school, I persuaded my Latin teacher to give me an entire pad of signed library passes so I could avoid the dreaded study hall — a place where tired students could place their weary heads in the crease of an open book and fall into a confused slumber — and go to the school library instead. Study hall proctors eyed me with suspicion every day, as if I were somehow avoiding the cruel and unusual punishment that my adolescent status deserved. They clearly thought I was getting away with something. Such was the pedagogical theory of 60 years ago.

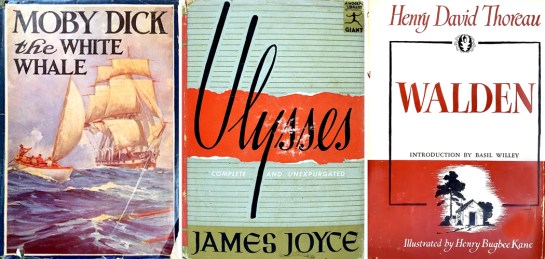

In college, there was little more delicious than burying yourself deep in the stacks, seated at a tiny, poorly lit carrel with a tower of scholarly tomes and doing research late into the night. These lucubrations were almost as delightful as the traditional student discovery of sex and beer.

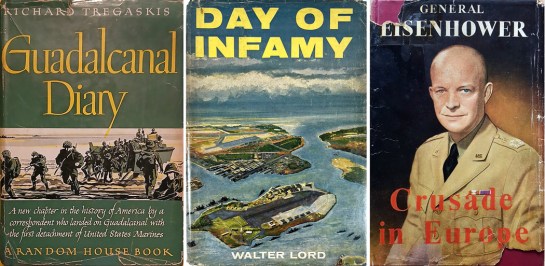

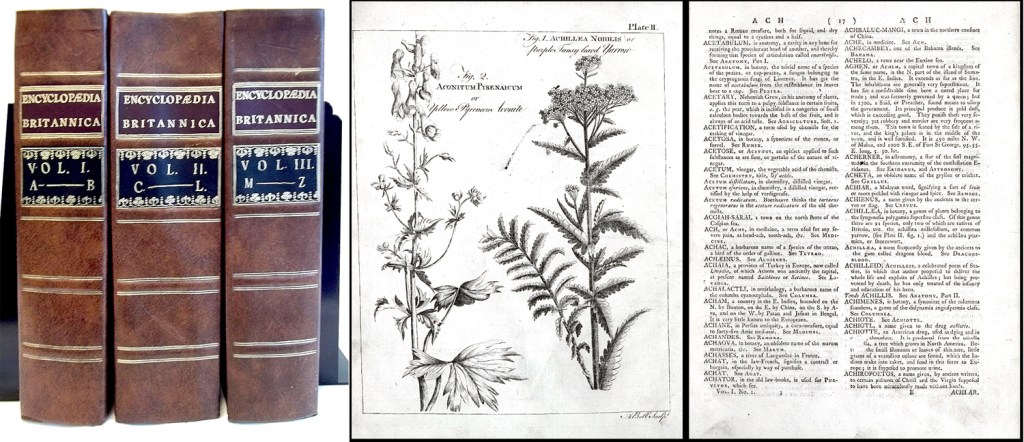

Even after graduation, I would go back to the university library and dive deep into its inventory — the stacks, called The Towers, were open only to students, but no one checked my ID — and I discovered many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore and managed to check out several rare books, including an 18th century printing of the sagas of Ossian — that famous fraud by James Macpherson. I was sorely tempted to pay the library fines and keep the book, but my conscience won out and I read the thing and returned it. (I have since bought a 19th century edition of the poems and it sits in my own stacks here in my tiny office — an office modeled on the site plan and measurements of the library carrel).

When I finally came to work for the newspaper, no assignment made me happier than one requiring a trip to the library, where instead of “reporting,” I engaged in “researching.” I was an indifferent reporter, but I was a great researcher.

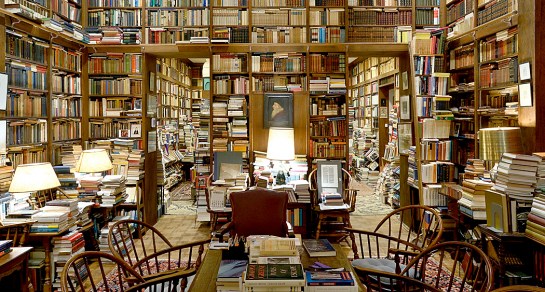

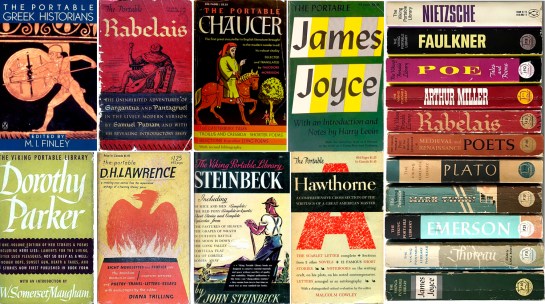

And now that I am retired, I live in my library — my personal library — where the walls are made from bookshelves and each book is a door, and while I spend many a happy hour in Google-land or riding the Wikipedia bus, it is still the feel of paper, the sound of turning pages, the smell of the residue of dust from the spine of a book that makes my pulse quicken.

Alas, libraries are under attack, mostly by irate villagers with pitchforks and torches afraid their children will be exposed to unregulated thinking, but also because the very act of reading is dying out, like endangered species or network TV.

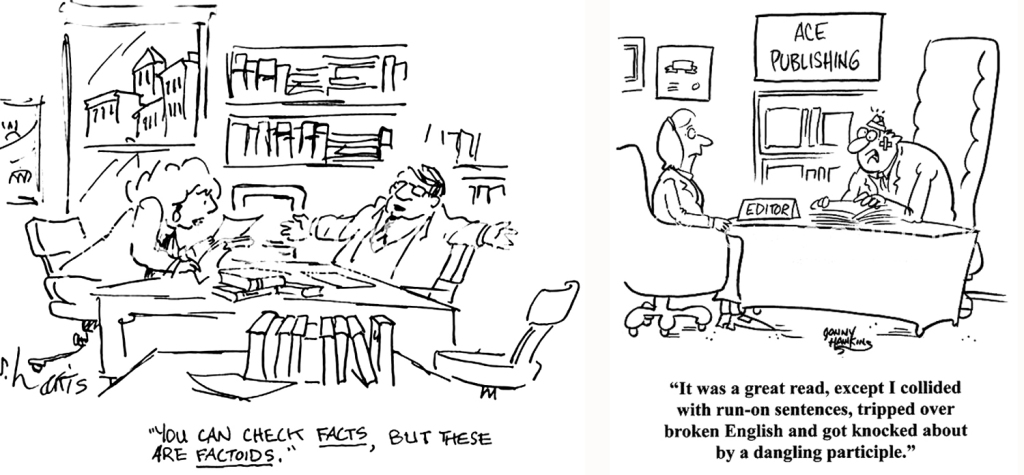

The newspaper where I worked had a library where I went to fact check what I was writing, but by the time I retired, it had been closed and the dear librarians who had helped me for 25 years had been offered buy-outs.

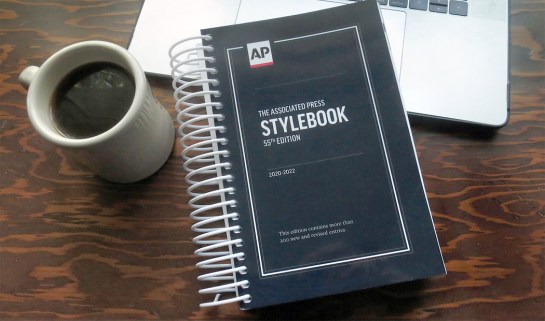

I had my own small library, several hundred reference books, at my desk, including a bookshelf jammed into the passageway behind my chair that had needed to be cleared by the fire marshal. But even that eventually became mostly decorative, since I could more quickly and efficiently find out birth- and death-dates of whoever I was writing about by Googling them on my computer.

I mourn the loss of libraries, and mostly the old-fashioned ones, with dark shelves piled high into corners of institutional basements, with their sequestered carrels lit by desk lamps, tucked into hallways.

The Library of Alexandria may have burned down, the Carnegie library buildings may have been rented out to non-profit foundations, the newspaper library has been thinned by a kind of bureaucratic deliquescence, and the public library has become a battery of computer screens, but I am here, behind the moat of my own books, vowing never to surrender.

“How could such sweet and wholesome hours/ Be reckon’d but with stacks and Tow’rs!”