The rankness of ranking

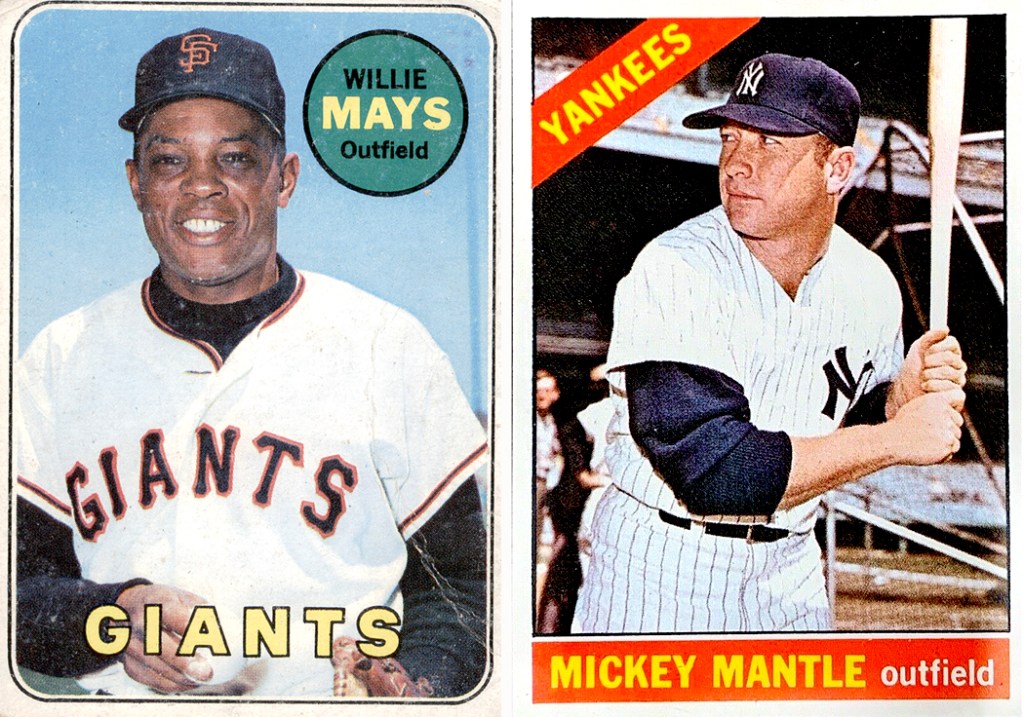

When I was a boy, one thing divided us into tribes: Was Willie Mays the greatest baseball player, or was Mickey Mantle? (This was before Mantle’s legs gave out).

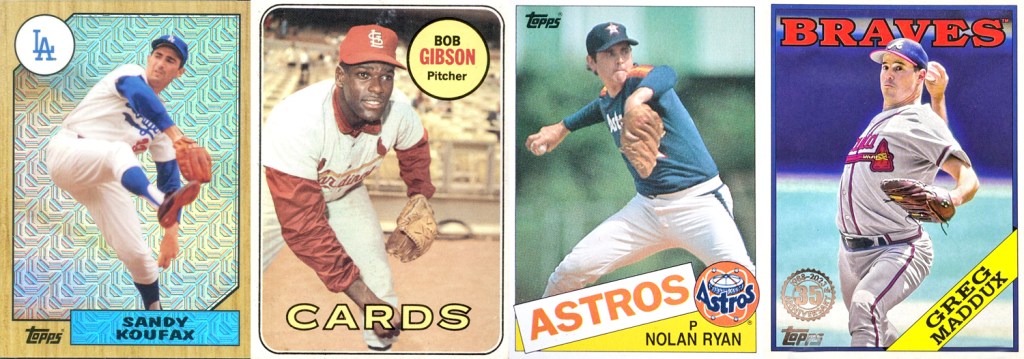

And of course, this was a silly argument, first because there were many other great ballplayers at the time, but mostly because choosing the “greatest” anything is a meaningless endeavor. (Just in the 1950s, we’re counting Stan Musial, Duke Snider, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Yogi Berra, Ted Williams, Gil Hodges, Jackie Robinson, Ken Boyer.)

But for us kids on the sandlot, it was a clear choice between Mays and Mantle. Was Mays the better hitter? Was Mantle as good a fielder? And are we comparing each player at the height of his abilities? Are we comparing lifetime batting averages, number of home runs, percentage of votes to enter the Hall of Fame? In the era of sabermetrics, there are so many obscure statistics to weigh, it all becomes bogged down and pointless. (Who is best at hitting with a 2-and-1 count, on an overcast day with men on second and third — it can get quite specific, i.e. quite anal).

By the way, I was a Mays guy. Perhaps I was swayed by the fact that my father hated the Yankees. He was National League all the way.

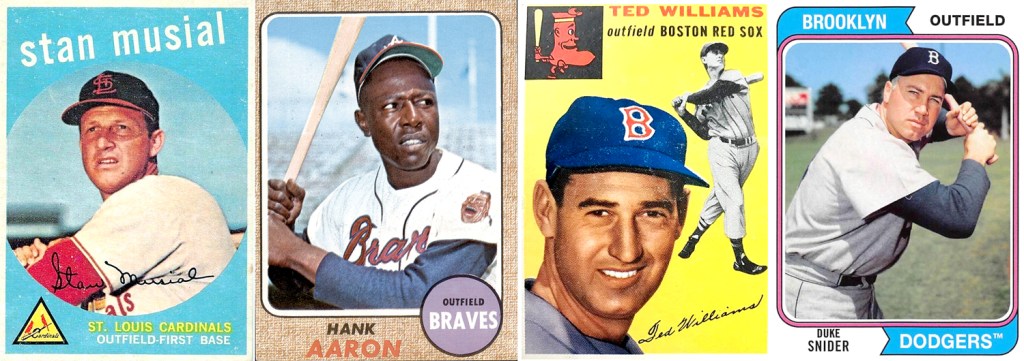

It’s all really quite silly. Above a certain level, players just count as exceptional and comparisons are meaningless. I mean, who was the greatest pitcher? Sandy Koufax? Bob Gibson? Nolan Ryan? Greg Maddux? They were all so different, with different strengths, and playing for widely different teams and different eras. (I remember when Roger Craig lost 20 games for the NY Mets, but was still considered the team’s pitching ace — how can you measure his quality when playing for one of the worst teams ever? How many games could Gibson have won playing for the 1962 Mets? They went 40-120.)

Ranking is a game, but one that is ultimately meaningless. Let’s face it, the most mediocre ballplayer in the major leagues is still hugely talented. We’re talking gradients of excellence.

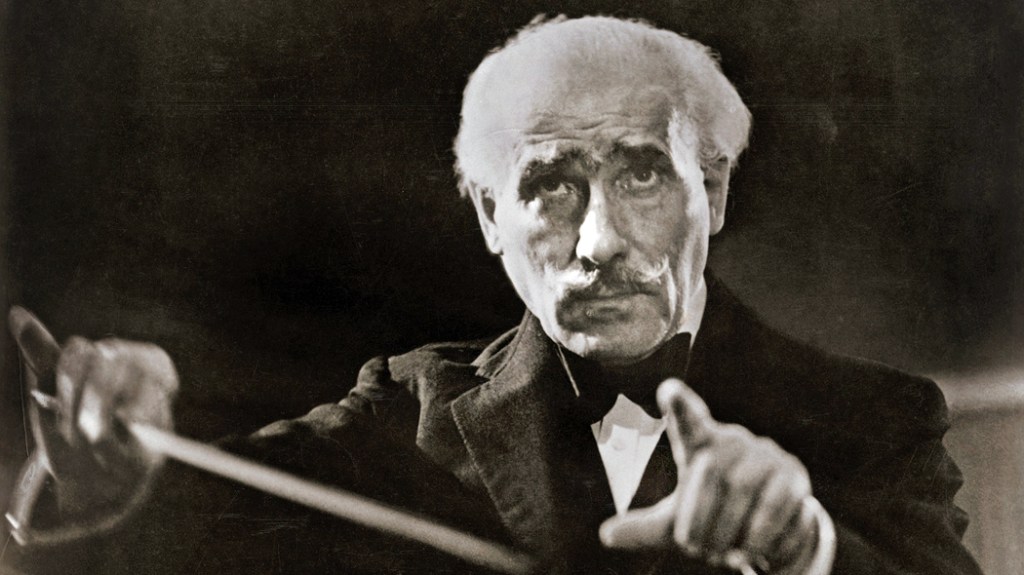

All this comes to mind when I remember how classical music listeners talk similar nonsense over the “greatest” conductor or orchestra, or recording of the Mahler Second.

I was guilty of such silliness earlier in my life. When I was in high school, there was no question in my mind that Arturo Toscanini was the greatest. I had all his Beethoven symphonies on LP. Later, having listened to a wider range of recordings, it was clear that Toscanini had his limitations. And not the least of these were the lousy quality of his recordings — they were hardly hi-fi.

Open any Gramophone book of recording ratings and you will find a “top ten” and the “best” recording of any particular work. Top 10 lists are immensely popular as clickbait on YouTube. Critics argue endlessly about why this Mahler Ninth is the greatest and that one is just awful.

But the truth is, that pretty much any recording you buy will give you the music you want, in a performance that is generally very good. Even a middling performance of Beethoven’s Fifth will give you 80 or 90 percent of what’s in the music.

The arguing usually comes over trivial details that the critic considers essential: Was the tam-tam audible in the finale? Was the oboe in the second movement a bit squeaky? Was the tempo in the finale too fast, or too slow? We all have these benchmarks that define what we demand from a performance of a particular piece. But should that disqualify an entire performance?

I have to fess up to a level of insanity here — I have 30 complete Beethoven symphony cycles (I used to own more, but have since divested of some). It was a decades-long quest for the ultimate set, the perfect lineup of Beethoven symphonies. Which is best?

Well, now, I see them lined up on the shelf, and I realize they are all fine. They all deliver the goods. They are quite different, from Karajan’s smooth unctuousness to Hermann Scherchen’s outright weirdness. Toscanini (which I still own, now on CD) is quick, abrupt and rhythmic; Bruno Walter is gentle, humane, and warm. And so, at different times, in different moods, I will choose one over the other for the moment. But they are all perfectly good. Why rank them?

Yes, there are some outliers, badly played or outrageously conducted — Listen to Sergiu Celibidache doing the Eroica and you wonder if you are playing the disc at the wrong speed — it’s the speed a novice orchestra might play for an initial sight reading. Glacial in a way that is just nuts. Or Roger Norrington, who conducts as if his bladder is bursting and he needs to get it all over with fast. (Norrington races through the adagio of Beethoven’s Ninth in 10 minutes; Bernstein in Berlin takes 20 minutes for the same music. You pays your money and you takes your choice.)

But the mainstream recordings, from George Szell to Andre Cluytens to Pierre Monteux to Joseph Krips, all give perfectly fine, reputable, performances, whether Beethoven, Brahms, Sibelius, Stravinsky or Shostakovich. They are excellent musicians with excellent orchestras (some, such as Maurice Abravenel, had less than excellent orchestras, but made them play on a level you can hardly credit).

So, we search endlessly for that one performance that will send us into paroxysms of ecstasy, that single transcendental recording, and each CD we buy we hope will be that one. Wilhelm Furtwängler recorded Beethoven’s Fifth 13 times from 1929 to 1954 (most of them miserably low-fi, even amateur recordings), and the Furtwängler cult will search endlessly for a 14th, hoping it will finally fulfill their hunger for the ultimate, the one after which they will gladly give up life with a satisfied smile on their faces.

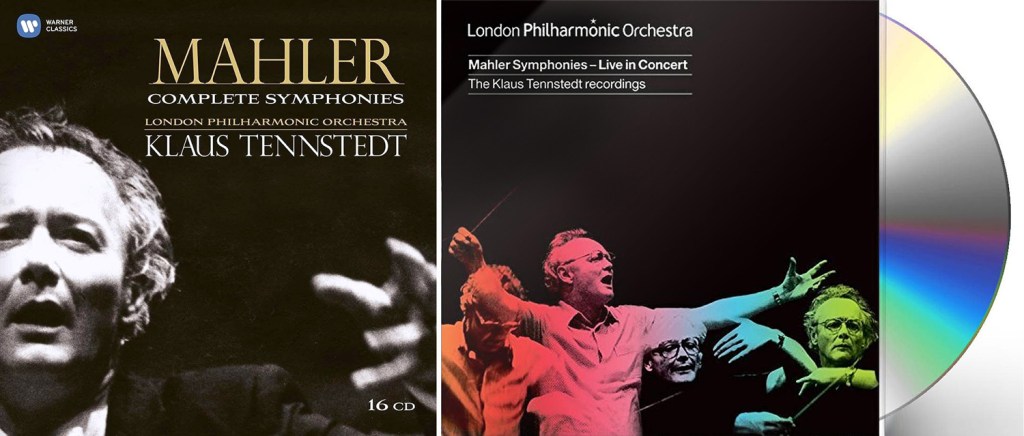

It is widely opined that Klaus Tennstedt’s live 1991 recording of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony is more emotional, more tragic, more vital than his earlier 1983 studio recording with the London Philharmonic. And that’s probably true. But if you only heard the earlier version, you would not be aware of anything missing or lesser in urgency or power.

Martha Argerich has a habit of recording the same few concertos over and over again (how many Beethoven second piano concertos do we need from her? She has recorded it at least 13 times, and I may have missed a few.) And some people swear one or another is “the best,” but they are all excellent, and whether you prefer her with Abbado or Dutoit or Sinopoli is nothing more than a matter or taste. If you own one and you like it, there is no reason to buy the others, unless you are part of the Argerich cult, and if so, there’s nothing we can do for you. (Classical music does tend to generate cults: Maria Callas, Celibidache, Arturo Michelangeli, Jascha Horenstein, Toscanini, and, above all, Furtwängler. Cult members will search world over for the one missing 1949 partial recording from a radio broadcast from Rio de Janeiro. The heart goes pitter-pat.)

(Just for the record, Argerich has recorded once with herself conducting the London Sinfonietta; and also with Vladimir Ashkenazy; Gabor Takacs-Nacy; Gabriel Chmura; Lorin Maazel, Charles Dutoit; Neeme Jarvi; Giuseppe Sinopoli; Claudio Abbado; Riccardo Chailly; Seiji Ozawa; Lahav Shani; and again with Takacs-Nagy Please make her stop. She’s wonderful, but she needs to branch out.)

Yes, you will undoubtedly develop favorites, conductors who play more to your tastes. I know I have mine. But I cannot in honesty say that the ones I like best are demonstrably better than the ones I have less affection for. Taste is a different issue from quality. Basically, with a few unfortunate exceptions, if a performance was good enough to justify the expense of being recorded, produced, distributed and promoted, it will be perfectly fine. You don’t need 30 complete sets of Beethoven symphonies.

So, one should not worry about what performance, what orchestra or conductor you get. Chances are, it will give you what you need. Bernstein or Walter; Mays or Mantle — they were each great players and picking one over the other is just silly.

The larger question in all this is why are Americans so obsessed with ranking everything? And if he, she or it isn’t No. 1, then they are a total loser! I think I will invoke my catchall mantra for all of our collective problems: “I blame advertising.” I usually add, “By advertising I mean marketing, by which I also mean propaganda.” Corporate indoctrination to only buy, appreciate and support only “the best” and nothing else has caused us to lose all appreciation for nuance and second best, even if the silver medalist is only one-hundredth of a second or a tenth of a point shy of the winner. As some clown of a coach once said, “Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.” Corporations run everything here, including sports and they have convinced us there is no spectrum of quality on which there can be equal, but different, nodes. Because there is no profit in that.

What, no Juan Marichal? And yes, Mays all the way! (My brother Pat might have some classical music opinions, but I sadly do not. He’s a self-taught French horn player in a Senior orchestra in Spokane, and gave away all his baseball cards years ago. I still have most of mine.)

Get Outlook for iOShttps://aka.ms/o0ukef ________________________________