Acquiring an acquired taste

Occasionally I get asked (OK, once) where should I start listening to classical music. Classical music is something that a few people as they age past Top 40 songs, come to believe they should begin to know, the way they should read Proust or watch foreign films.

Philip Larkin mentions the drive in his poem Church Going: “Much never can be obsolete,/ Since someone will forever be surprising/ a hunger in himself to be more serious.”

I have been listening to what is called classical music for 60 years, and my first thought is that classical music does not exist. Not really.

What is called classical is a combination of old church music; popular music that has been around so long, it no longer sounds like the pop music we know; and music meant to entertain, first, a class of aristocrats who could afford to pay for it, and then an aspirational middle class that took up the buying of tickets.

It wasn’t until late in the 19th century that anyone really considered such music “classical.” And only in the 20th century that most symphony orchestras were organized to play what in the past had just been music, but was now given this new label.

Until then, most concerts consisted of new music mixed with a few old favorites (much like modern pop music — they wanted to hear the hits). And so, old standards became classics.

Not all of the old standards were heavy and serious. Mozart wrote tons of divertimenti to be played as the count and countess ate lunch. It was only meant to sound nice, with catchy tunes. Yes, some classical music is meant to evoke deeper thoughts and emotions, some even meant to change lives.

But there is pop music that is serious, too. Consider the Beatles’ A Day in the Life, or Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody. They aren’t always short.

And so, when you ask about classical music, you aren’t asking about a single thing. If you were to open up that can of worms and try to learn what classical music has to offer, you will have to recognize that no one thing can suffice. Nor any one style; nor any one century.

If there is anything that marks music as classical, it is its length. Most tunes last three or four minutes, while a symphony can run anywhere from a half-hour to 90 minutes. The popular music is meant to put a tune in your head and you like it (or not) and may sing it to yourself as you wash the dishes. Such music is usually meant to be absorbed passively.

What is called classical tends to be more like a story, even a novel, with multiple characters and changing moods, so where you start is not where you end up. It is music you pay active attention to. It goes somewhere and you have to pay attention to notice the plot.

The story told in music, though, is not one that can be translated into words. It is one you listen to as it unfolds in musical terms: the melody changes, sometimes broken into pieces, the harmony turns grim or lilting, sometimes the melody might be played half-speed, or faster, or even upside down. These are all part of the musical story-telling.

So, what do I say to my friend asking advice on how to start listening to classical music?

The complaint I hear often is that classical music all sounds the same. It doesn’t. And so, I want to offer examples both of the stories and of the diversity. And I want to start off with a symphony with the clearest, most direct “story” to tell.

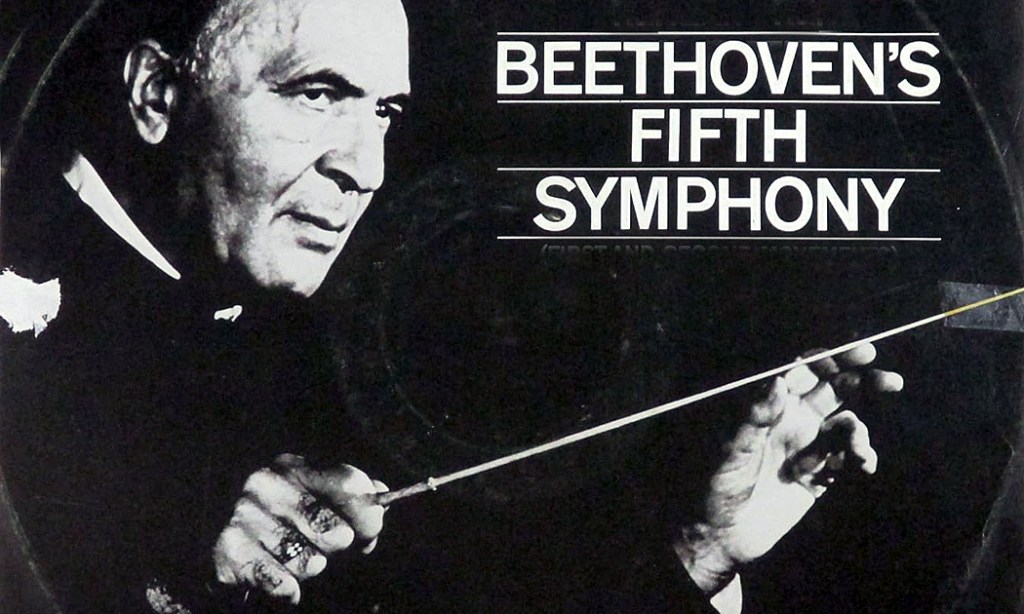

If there is any single place to begin, it is with Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, or, more formally, Symphony in C-minor, op. 67, first performed in December, 1808, in a freezing cold concert hall in Vienna, along with a host of other new works by the composer, making for a concert lasting more than four hours. For all that music, the orchestra — a pickup ensemble paid for by Beethoven himself — had only a single rehearsal to work out the kinks. In one of the pieces played that evening, the orchestra got lost and had to stop and begin the whole piece all over again.

But that Fifth Symphony eventually became iconic — the single stand-in for all of symphonic music.

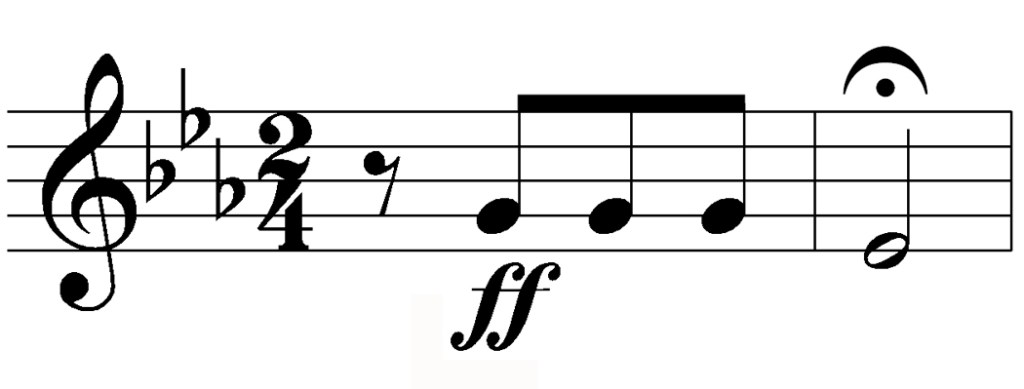

It begins, as almost everyone knows with the heavy tread of the dah-dah-dah-DUMM. Those four notes are played over and over through all four movements of the symphony, sometimes straight, sometimes altered, sometimes as a drumbeat underneath another tune. I once counted in the symphony score more than 700 repetitions of dah-dah-dah-dumm. That works out to once every three seconds of music from start to finish. It’s almost OCD. It’s no wonder the notes are often compared with hammer blows.

The symphony is in the minor key, a key of angst, anger, uncertainty, which Beethoven underlines by having the music stop outright several times after we hear the four-note motif. As Peter Schickele said, in his comic sportscast of the symphony, “I can’t tell if it’s fast or slow, because it keeps stopping.”

But it picks up steam to an intense, driving rhythmic motor, all in that relentless C-minor. It blasts you over the head with it. The first movement (of four) lasts, in most performances, only about five minutes, but you may very well be worn out by all that hammering and minor-keying.

The second movement is a relief from the drive of the first, but the dah-dah-dah-dumm is often there, heard beating away in the bass line. The third movement starts with an ambiguous arpeggiated melody in the basses, but then brings back dah-dah-dah-dumm as a main theme, with the drive of a forced march. The movement doesn’t really end, but rather morphs into a chaotic repeated note pattern that doesn’t seem to be going anywhere, until … until… it does — and it explodes into a big, brassy blast of C-major — the major key the entire symphony has been trudging toward for all its length. The feeling is absolutely triumphant. The spirit soars.

And yet, if you listen carefully, you will recognize that those happy, brilliant tunes are actually a metamorphosis of the dah-dah-dah-dumm, buried in a longer, rising optimistic melody. And at the very end, Beethoven drives home that C-major with 25 bars of pounding C-major chords in the full orchestra. You know you have reached the finish line with the last long-held chord. Having won it, he’s not going to let go.

The story the symphony tells is from anger and angst into triumph and joy. It is this long development of an idea that marks what is called classical music as different from popular music.

And even in classical music that doesn’t have the symphony-long coherent story to tell, each movement has its own plot and narrative. The most common narrative in classical music is presenting a theme or two, or three, in order, then mixing it all up, taking them apart, replaying them in foreign keys and disruptive orchestration, and then, finally, bringing them back in something like their original form so that you have a satisfying feeling of having returned home after a journey. Roughly half of all classical music is built on this pattern — with infinite variations.

It is the surprise variations from the standard pattern that often delights music listeners. But to get the variants, you have to have become familiar with the expectations. It is hardly different from knowing the general plan of a TV sitcom, and being delighted when the show gives you a turn on your expectations. In a modern sitcom, you almost always have a main plot, a secondary plot, and a third, smaller background action, and they alternate in your attention, but are all wrapped up by the end. Same with a symphony or sonata.

Next, about classical music all sounding the same (I have my own ignorance, too: For me, all pop music sounds the same). I have come up with a list of five classical pieces to spread the parameters. Each of these pieces can be found on YouTube to be listened to for free.

Orchestral music is what most people think of as classical music. But there is so much more.

Let’s start with some choral music. Before the late 17th century, most art music was vocal, and most often for the church. What instrumental music there was was usually improvised, rather like jazz.

So, first, listen to Spem in Alium by English composer Thomas Tallis (1505-1585). It is a 40-part motet setting the Latin text “I have never put my hope in any other but in thee, God of Israel.” (Spem in alium — “Hope in other”). It was written about 1570 for a combined eight choirs of five voices each.

It starts with a single soprano voice, adding others until, about three minutes into the piece, the entire five choirs all burst forth in a glorious racket. It is quite sublime.

Then, let’s go the other direction. In 1913, Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps (“The Rite of Spring”) was premiered as the score to Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreography for the Ballets Russes in Paris. That premiere famously caused a riot. Stravinsky fled the theater in fear for his life. Or so he claimed — one never knows just what to believe in a self-mythologizing artist.

The music is rhythm torn apart, pounded home as part of what Leonard Bernstein called “Uncle Igor’s Asymmetry Machine.” It tells the ballet story of primitive Russian society and its ritual sacrifice of a young woman who dances herself to death. With its riotous dissonance, pounding percussion, and extreme orchestration, it remains perpetually modern.

But we should not forget chamber music — music for a small group of players, often just two, such as violin and piano. César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A-major is about the most tuneful sonata ever written. He wrote it in 1888 as a wedding present for the famous violinist Eugene Ysaye.

Its four movements borrow tunes from each other, and so although the movements are quite distinct emotionally, they are all tied together by the memorable melodies.

And I cannot forget song. Most of the great composers also wrote songs, though they are nowadays called lieder, which is just the German word for “song,” but gives a higher-toned, more prestigious ring to the name. But they are songs nonetheless.

The greatest of these classical song-writers is undoubtedly Franz Schubert (1797-1828). Poor all his life, and hardly recognized as a great composer by any but his closest friends, he was a gushing fountain of melody. His song Erlkönig tells the story of a father and son riding through the night on a horse, stalked by the evil elf-king who wants to take the boy. The child screams in fear, the father tries to protect him, and the goblin tries to seduce the kid away. It is a frightening song, but full of tremendous melody.

This should give you some sense of the incredible range of the art music of Western culture. And a start in classical music.

Next: A look at the changing eras of classical music