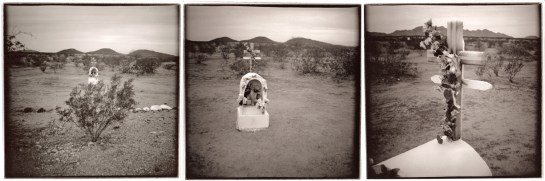

Many decades ago, when I first came through Arizona, I passed through a landscape so surreal that after I got home, I could not be sure, when I went back to my job in Virginia, that I had actually seen what I had seen: mountains and mountains of grayish-tan gravel, in a town so beaten down, so weathered, so spavined and dried out, that could not be sure that I had not dreamed the whole thing during a nap after an ill-advised meal of rarebit.

When we finally moved to Arizona, I rediscovered Miami-Claypool and it lost nothing of its Twilight Zone weirdness. To those of us not familiar with copper mining, the thought that humans could build cordilleras of utter waste — post-apocalyptic poetry — was hard to credit. Part of me wanted to live there. Nothing could possibly feel day-to-day, ordinary, or boring in such a nerve-frayed landscape.

If you drive east from Phoenix, out past Mesa, past Apache Junction, into the desert past Florence Junction and climb up into the hills, you will find a string of mining towns, mostly abandoned or dying, or hanging on by their fingernails, beginning with Superior. It was one of the locations for the 1997 Oliver Stone film, U Turn, and it feels like it could have been dreamed up by a Hollywood set designer. In 2005, a sci-fi film called Alien Invasion Arizona was filmed there. It isn’t quite a ghost town, but you could easily place a season of The Walking Dead there.

Superior’s biography is like so many copper towns in Arizona part of a history that almost no one thinks about. It is an industrial history, full of smokestacks and labor disputes, and fills in the space between the six-gun Old West of popular mythology and the modern and often banal state of tourism and retirees.

Unfortunately, it is an industry that cycles with the international market price of copper: The price plummets and Arizona mines lay off workers and shut down. If the price recovers sufficiently, the mines start up once more. Mine-worker families face an uncertain life.

The history of Arizona’s mining towns is generic. Whether it is Bisbee or Bagdad, Morenci or Globe, there is a familiar tale, altered only with variations on the tune.

For each, it begins in the 1860s or ’70s, when an army officer or a prospector picks up a rock and smiles, recognizing it as ore. Usually, they were looking for gold. Often what they got was copper. Then there is a period of individual prospecting, usually ending in bankruptcy all around. Then, financiers from New York or San Francisco add capital and mining picks up on an industrial basis. Towns spring up, usually shanty towns precariously perched on gravelly hillsides near the mines. During boom years, the towns grow. Wood is replaced by brick; large hotels are built and streets are paved.

One company buys out another until huge corporations are formed with names like Phelps Dodge and Magma. Ultimately they become multinationals with many interests beyond copper.

Between the wars, the underground mines are largely replaced by the great pit mines, man-made miniature Grand Canyons of ore-dig.

But then, after boom years and some bust years, the mines play out or are flooded or copper prices fall and the towns surrounding the mines die out.

Or, in a few cases, they persist, either as mining persists, as at Morenci, or as the towns find new purpose as tourist destinations, such as Bisbee, or county seats such as Globe.

But the past also persists, and those interested in this forgotten past of Arizona can still visit many of the best locations.

Mining hit Superior in 1870 when silver was discovered and the Silver King Mine became one of the richest silver mines in Arizona history. But in 1912, Boyce Thompson bought the mine, formed Magma Copper and the area became one of the great copper mines. The smelter closed in 1971; the mine remained in operation until 1982. The mine has sporadically been worked since, depending on copper prices. But Superior, taking a cue from Bisbee and Jerome has tried to position itself as a tourist location. The wooing of Hollywood has been part of that resuscitation and the town has its own film board.

South of Superior, are mines at Mammoth and Kearny and Hayden, home to the ASARCO smelter complex, which services several of that company’s state mines. It is rich in mining history, and union grumbling is still part of the town: One abandoned building has “Union Yes! Forever” painted on it, with one of the “Ns” in “Union” painted backward. The first parts of the plant were opened in 1912, and now it covers 200 acres with a smelter smokestack 1,000 feet tall. Nearby Winkelman and Kearny are worth seeing, also, and the now-closed San Manuel mine is several miles south near Mammoth. The tell-tale tailings ridges run for miles.

ASARCO’s big open pit Ray Mine is 22 miles south of Superior on Arizona 177. The Ray Complex covers 53,000 acres and is the second largest copper mine in Arizona. There is an overlook off the highway that affords an unofficial peek at the mine.

But this is a detour. Back to Superior, and driving east up into Queen Creek Canyon and beyond to Miami-Claypool and its veritable Himalayas of detritus, where you will see what will be, depending on your esthetic sensibility, either a great warning of industrial environmental depredation, or an awesome visual wonderland, an eruption of surrealism in the middle of the quotidian.

The town looks like it was dropped as litter from some passing god’s chariot, scattered on the hillsides to either side of U.S. 60. The smelter smokestack rises to the north, over the black drapings of slag across one tan tailings hill.

The town is younger than most of the mining towns in the state. In 1909 the Miami Copper Company began operations on the hills beside Bloody Tanks Wash. For a while, it was a rival to Globe, where the Old Dominion Mine was one of the biggest producers. But Globe ceased being a mining power in 1931 when the mine flooded, and Miami became the center, not just of mining – several mines are nearby, including the Pinto Creek open pit – but the major smelting location for Phelps Dodge.

Now, the townsite, with its bridges over the wash looking like Venetian canal bridges gone terribly wrong, is home to many antiques stores. Unlike many old mining towns, the industry is in full swing, and the mines and processing plant prosper and wane with the price of copper.

Past Globe you enter the San Carlos Indian Reservation. Take a right down to Coolidge Dam and San Carlos Lake. Monuments to civilization are always so much more compelling when they are stuck in the middle of nowhere, like Shelley’s Ozymandias or Catherwood’s Palenque.

At least, that’s what comes to mind when you finally come upon Coolidge Dam, standing like a sentinel in the grass and hills of the Apache reservation.

Built in the late 1920s, it comes from that great era of dam building and dam architecture. Although it is much smaller than Hoover Dam on the Colorado, it shares an obvious family relationship, with its Art Deco details and horseshoe curvature. It looks like one of the great, archetypal dams.

It reaches a climax in two giant Deco eagle heads near its lip that watch over the downstream Gila River as it enters the Needles Eye Wilderness. They are eagles that pronounce the word “federal” with authority.

It was the Bureau of Indian Affairs that built the dam, to allow the San Carlos tribe to make use of the fluctuating water supply of the Gila. In 1994, the dam overflowed, with water released in such quantities through its spillways, that they had to be repaired. On the other hand, the lake has shrunk to practically nothing at least 20 times in its four-score years of life. In 1977, the lake got so low, there was a major fish kill, with an estimated 5 million fish going belly up. It took five years for the lake to recover.

At low water, the lake must look the way it did when the dam was dedicated in 1930, when humorist Will Rogers looked out at it during the ceremony and joked that, “If this were my lake, I’d mow it.”

By 2015, it could have used another good mowing, because the lake was down to about 5 percent of capacity, leaving most of the dam high and dry, exposing what is supposed to be under water. The current El Niño has raised the level once more.

Three great bulbous rounds of concrete make up the upstream part of the dam, and they are exfoliating sheets of concrete as they age, and looking more and more like a ruins in the making.

If you take the pilgrimage to see the dam, you might as well continue along Reservation Route 500 for 30 miles until it reunites with U.S. 70 at Bylas. Few drives in Arizona are as peaceful and solitary. Just watch out for the potholes.

Continue down U.S. 70 along the Gila River and farmland to Mt. Graham and Safford. From there you head toward Clifton and Morenci, up in the hills. There is a “short cut” — the 21-mile Black Hills Back Country Byway, which takes you through wilderness on a gravel road. This is what Arizona looked like when Geronimo hid in these canyons and arroyos. After you cross the Gila River on its Depression-era concrete bridge, you can see a parody “shining city on the hill,” Clifton, like a mirage.

If you really want to see the industrial power of Arizona, you can do no better than to visit Clifton-Morenci in Greenlee County. The largest open pit copper mine in the nation has spread so many miles across, it actually ate up the original town of Morenci.

The Phelps Dodge mine can be viewed from an overlook on U.S. 191, 11 miles north of Clifton. It is a humbling experience: like looking at a manmade Grand Canyon, covered with trucks the size of five-story buildings busting dust up along the miles and miles of mine roads in the pit.

One truck can haul 270 tons of ore on tires 12 feet in diameter. The biggest trucks carry 320 tons.

Morenci is still a company town, the last in the state, where all the housing is company owned, and all the workers and families shop at the company store.

The mining potential of the area was discovered in 1865 by passing soldiers. The first mine opened in 1872, but things took off when Phelps Dodge entered the picture in 1881. The open pit was begun in 1937, since then, 4.1 billion tons of ore and rock have been dug out, leaving behind a hole big enough to see from outer space.

The industrial complex is impressive. Miles of corrugated-metal processing plants and piles and piles of tailings and slag.

Clifton, a few miles south, is practically a ghost town, but filled with the same kind of buildings that give Bisbee its period charm. Only in Clifton, they are rather more like Roman ruins.

Seeing these old mining towns, like Clifton, Miami or Winkelman, can leave you feeling quite conflicted. They are clearly evidence of monumental environmental destruction. Poison waters run off the tailings piles and nowadays have to be captured and treated, but in the past, just filtered down to the streams and water table. Whole mountains have been turned into holes in the ground. Ash heaps make new mountains. Lives are burned up, too. Miners attempting to find better conditions could find themselves dumped off a train in the emptiness of New Mexico and told not to return. Huge corporations buy up the hard work of the original prospectors and squeeze the profits out of the land, like water from a dishcloth. The land has been turned gray and dusty, and tire tracks the size of riverbeds gouge out the roadways. The air is heavy with dust and fumes, and men swarm over the desiccated heaps like ants on an ant hill.

Yet, it is hard not to be awed by the sublimity of such hugeness, vastness, even if vast destruction. One is left with two hearts.

In the 18th century, there was a fad for paintings of Classical ruins. Such paintings were called “picturesque,” and they depicted not merely the architecture of Rome and Greece, but the vines growing up the stones, and the peasants building cooking fires below the aqueducts. The cracked masonry, fallen blocks, glowing in a beautiful sunset, set 18th century sensibilities into a dither, fanning themselves in admiration of the beauty — a beauty that told of death and decay, of the falling of empires, and the persistence of life below the arches and gables. There is a sense of grandeur, even if we only live in reflection of it.

And while I cannot avoid seeing the landscape as some sort of movie set for a new Mad Max film, neither can I deny the grandeur of the landscape, the sense of loss that fuels the emotions, the sense of something larger, older, and more significant than myself alone.

Much of the mythology of Arizona revolves around cowboys and Indians, some fantasy version of the “Old West.” (Somehow, Scottsdale gets to call itself “the West’s most Western town,” while in reality being a commercial real-estate empire filled with shopping malls and freeways). The mythology is a commodity. Yet, there is real myth — the feeling in your psyche of the expansiveness of history and the world — in the union battles, corporate dealings, dying towns and Dante-esque pits into the earth.

As you head north out of Morenci, you enter the mountains and head to a completely different Arizona.