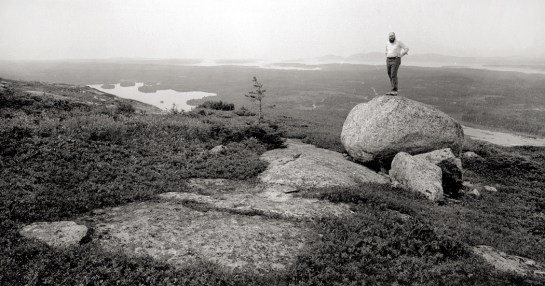

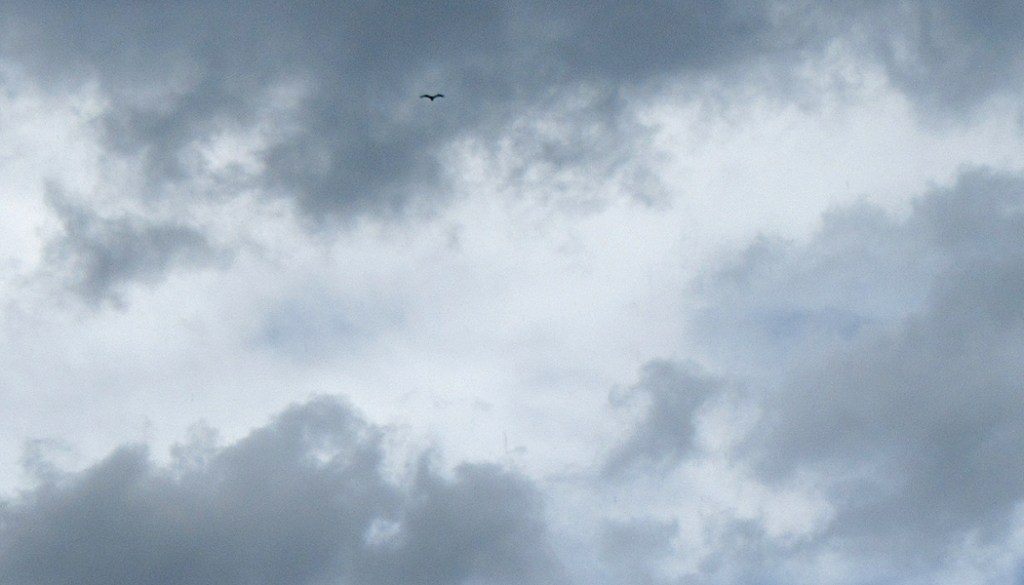

On Schoodic Mountain, Maine

I am within days of turning 78 and I feel my age, slowing down and dealing with new aches daily. I seem to be in reasonably good health, considering. But I don’t know how long I have left, and the length of string in front is clearly shorter than the length trailing behind. I am increasingly aware of mortality.

And I have been considering all the things I have made and written over those piled decades and sometimes wonder why. Nothing will happen to any of it after I’m gone: It will eventually find some landfill somewhere. And part of me is perfectly alright with my life’s effort in words or images being utterly forgotten. Most of what anyone has produced over the millennia is long forgotten, and it’s fine. But I did a few things moderately well, and I can look at it all and note it.

Over the past weeks, I have been spending time trying to consolidate a definitive version of some of the work from over the years. One has a tendency to take the long look and attempt some sort of codification of the evidence of a life lived. And so, I’ve been editing and winnowing.

It is related to the unavoidable sadness one feels, having spent that life learning a huge trove, not merely of facts, but of useful experience — things we never understood as arrogant youths, full of ourselves and dead certain we were smarter than all those benighted generations that gave us birth — and knowing there is no way to impart that accrued experience to the children and grandchildren we love, that they will have to go through all of it again, on their own, and in turn come to rue that they will not be able to keep their own children and grandchildren from the same pains, mistakes and ignorances.

And it will be the same for the physical evidence of that experience — the art and writing. So, I look over a lifetime of production and question to what end?

Even I am astonished at the amount of work put in, a constant chugging away at the production machine, pictures and paragraphs. In 25 years at the newspaper, I wrote more than two-and-a-half million words, and since retiring, I have written another million-and-a-half on this blog — with another 100 essays written for the Spirit of the Senses website in Phoenix, having also given at least a score of well-researched lectures for that salon group. There are also an uncounted number of letters penned, and also both fiction and poetry.

To say nothing of the tens — maybe hundreds — of thousands of photographs I have made.

I have always been this way. I didn’t think about it when I was a boy, but even before first grade, my idea of fun was a pile of paper and a pencil or crayon and I would spend hours drawing. Most kids do that, but most slowly lose the need as they grow up. In high school, I was given access to the darkroom and began making photographs, while also writing for the school newspaper. Always scribble, scribble, scribble. Eh, Mr. Nilsen?

After college, I found work writing, editing and making photos for a Black weekly newspaper, where I pumped out a weekly cooking column and the “Dear Carol” advice to the lovelorn column, in addition to writing the editorials and coming up with the headlines. (My favorite: When the iconic Greensboro, N.C., nightclub closed, I wrote in giant 128 point type, “Cosmos Folds!” Thought it a grand joke.)

In the single month of March of 1980, I wrote 500 pages of letters to friends, on a tiny plastic aqua-colored portable typewriter on a tree-stump “desk” in the back yard. When I finally began work at the daily paper in Phoenix, I averaged about three stories a week. I thought I was being lazy, but apparently I was producing more than most. (At least, that’s what my editors told me).

I would use the word “creating,” but that seems too important for what I was doing. I was producing.

Los, with his forging hammer, by William Blake

There is a character in poet William Blake’s obsessive mythology called Los, and he is one of the four main “gods” of human psychology, and Los spends eternity forging an endless chain. Why he does so is irrelevant: It is what he does. He is defined by it. He produces. It is what I have done: produce.

Many jobs in life call more for other talents. Nurses and doctors, for instance, or office workers who keep the paperwork flowing, or in selling or organizing. The actual creation of something new is not for them the goal. But in my life, like that of Los, all that matters is production. Make. Make. Make. I cannot imagine spending my life without making stuff.

And so, I am going over the thousands of files stored on computer and CD-ROMs and winnowing down what I think has been the better examples, and working on them to create the best or final versions “for posterity,” by which I mean, so I can look at them and contemplate what I have spent my life doing.

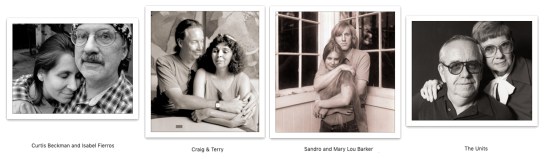

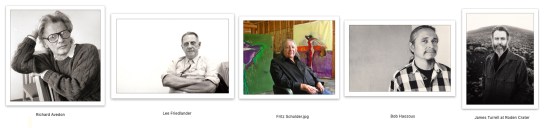

I just finished editing the bulk of the portraits I have made, cleaned them up, re-framed some, improved contrast and tone, and come up with a final version. If I were to present a portfolio, these images are what I would offer. I have about 200 such images in the file.

I previously did the same thing for the nudes I took over the years; there were fewer of them and even fewer of those were worth saving.

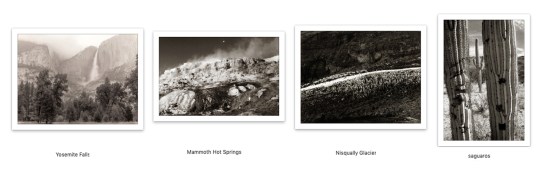

There have been uncounted thousands, probably tens of thousands, of landscapes I have pointed my camera at. Most are just snapshots — memories of travel — but there are hundreds saved intended as works of art, and shown in gallery exhibits and printed in books

The earlier ones are more clearly derivative, but gave me lots of practice printing in the darkroom, so that I became an excellent printer of silver images. The longer I kept working, the more individual my landscapes became.

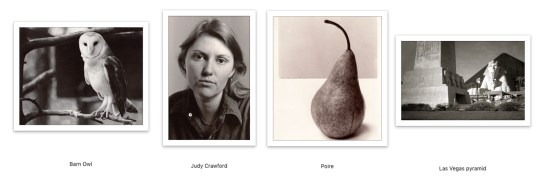

Most of my photographic work has been in clear genres, such as portrait, nude, landscape and still life.

One subject that has remained as a visual source of amazement over 50 years of making images are trees. I have thousands of prints of various trees in various seasons and weathers.

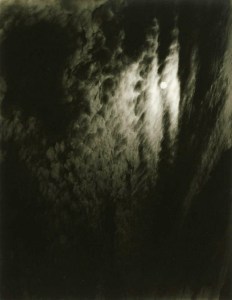

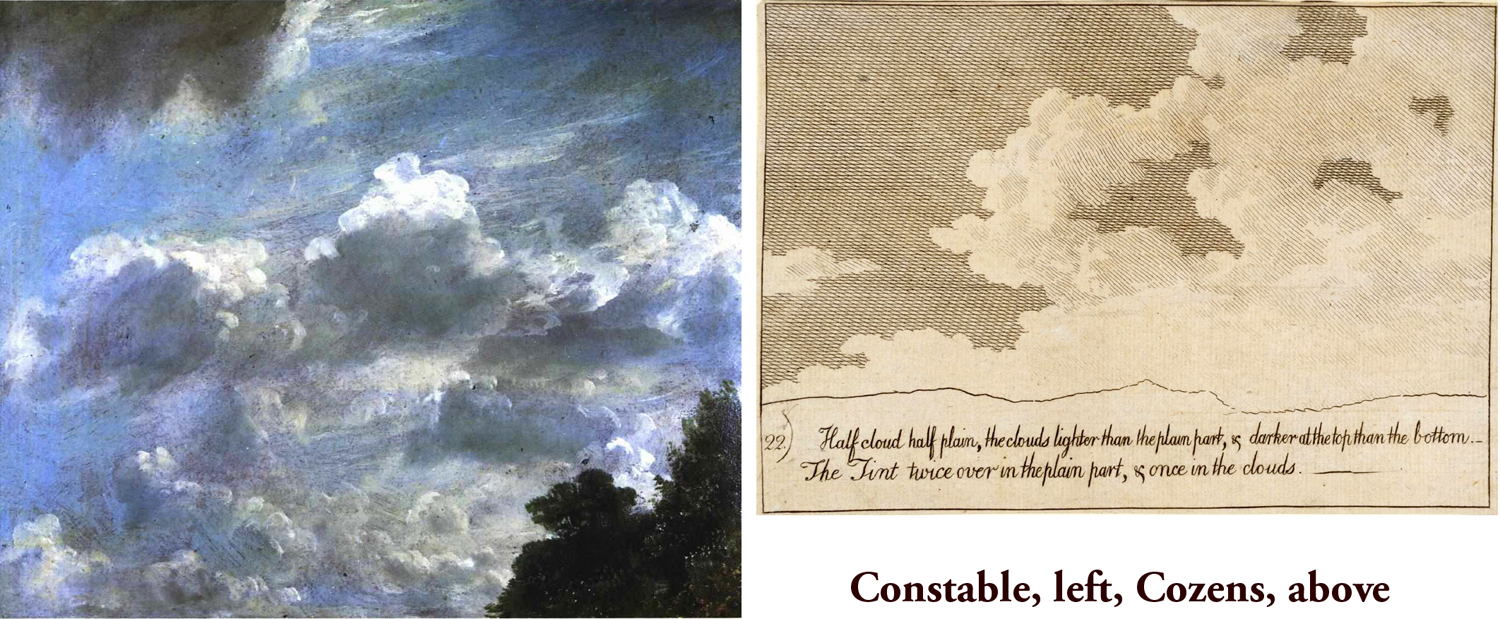

And, because of when I grew up — in an era when Abstract Expressionism was king of the hill — I add to those genres a search for abstractions.

And even, non-camera work, where I played with the chemicals and papers to make my abstractions directly in the darkroom.

About 25 years ago, I began making photographs in series — collected in portfolios of between 10 and 20 prints each — made in various gardens, including public gardens and the back yards of friends and family. I must have made scores of these boxes, each with its title, and meant to be understood not as individual images, but as a kind of suite to be taken whole.

And with images made over the course of a few hours, tapping the shutter at whatever caught my eye as deserving its attention.

I expanded the series idea into images I found outside my airliner when flying around the country, a series I titled Window Seat.

And another using a cheap toy camera (a $2.98 Diana) at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in southern Arizona.

And another made from clouds on one particularly stormy afternoon from my back yard in Phoenix, collected in a book titled Monsoon.

Where does all this need to keep creating, keep producing come from? It is just my nature. I can’t help it: It keeps mind and hands busy, engaged, interested, alive.

I’ve made linocuts, drawn with pen and ink, played with graphic design, and even, when my wife needed a step-stool for the kitchen, I built one from birch wood in the shape of a jack rabbit.

None of this means I feel especially talented or important, but just that putting things into this world that hadn’t existed before I made them seems as if it is whatever purpose my life has been made for.

When I was newly minted and 20 years old, I thought I would be an artist or poet. It was a goal. But it didn’t take long to give up such an idea. Instead, I began writing and making images. The focus was no longer on my identity, who I thought I was, and more on engaging with the world. Looking outward rather than being stuck with self.

I’ve known plenty of genuine artists; I don’t count myself among them. But I am doing something analogous.

I didn’t care if I was an artist. I was more interested in understanding the world, either visually or conceptually. And not so much understanding as simply experiencing it. I can’t say that self evaporated — I have always had a strong sense of self, as anyone who knows me will admit under muffled giggles. But that it didn’t matter.

And so, a lifetime of making things was not spent in any ambitious attempt at public recognition. I certainly could have written books or sought more gallery shows, but, as comic Steven Wright once put it, “I have ambition, but without the drive.” But I have been driven to use my words and my camera to see better, to connect better, to make objective documents recording what I have seen or learned. Making pictures forces my attention.

So, when I question having spent my life making and producing, and what it was worth, the obvious answer is not in the rewards of having made, but in the immediate doing. The meaning is in the act.

I will stop when I no longer breathe.

Click on any image to enlarge