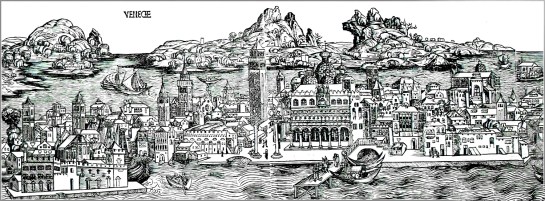

“Venice,” woodcut by Dürer

In 1494, at the age of 23, after years of apprenticeship as an artist in Nuremberg, Albrecht Dürer left Germany to visit Venice and Italy and find out what all the Hoohah was about. He was amazed at what he saw and when he returned home to Germany, he brought the Italian Renaissance with him. He went back south for seconds in 1505 and stayed for over a year, soaking up the influences. It was what he had to do if he wanted to see what the Big Boys were doing.

If you wanted to see, you had to travel. There were no full-color coffeetable art books to thumb through. If you wanted to see the work of Bellini, you had to go to Venice; for Raphael, to Rome.

“Goethe in Italy” by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, 1786

In 1786, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, then age 37, made the trip, this time to see the Roman and Greek sculpture that had been so highly praised in the work of Johann Joachim Winckelmann. He stayed until 1788, studying more than the statues, including many statuesque young women, which he later wrote about in his book of poetry, Roman Elegies.

For most of history — until improvements in color printing in the middle of the 20th century — the only way to see famous art was to leave home and go there. Yes, there were engraved black and white copies published, and later monochrome halftones, but you could not really get a sense of Rembrandt or Titian without traveling.

It gave rise in 17th century to the practice of upper-class families sending their sons on the “Grand Tour” to become educated and cultured. From the 1600s to about the middle of the 19th century, it was common for well-off young men to take a “gap year” — or two — to visit the Continent and see the sights and become men of the world before taking up their roles in government or business. Of course, many of these youths were more attracted to the live demoiselles and regazze than to the canvas madonnas.

“Rose,” Philbert-Louis Debucourt 1788

It wasn’t just visual art. Before recordings, if you wanted to hear a Beethoven symphony, you had to attend a live concert. If you lived outside the city, you had to travel to get to the concert hall. Bach famously walked 280 miles from Arnstadt to Lübeck in order to hear Buxtehude play the organ. Even to hear now-famous symphonies and concertos you likely had to wait years between programmed performances. You might be lucky to have heard Beethoven’s Fifth once or twice in your life. Now, it seems, you can’t get away from it.

Today, when you can own 30 different CDs of the Beethoven symphonies and have your choice from Furtwangler to Norrington; you can fill your bookshelves with illustrated volumes of any artist you want; and watch endless YouTube videos about the Mona Lisa, it is important to remember that they are not the actual experience of the art in question, but varyingly faithful simulacra. You still need the real thing. A three-inch color plate of Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa cannot replicate the experience of seeing the real thing.

And so, we go to museums and galleries to get to know the art that is our cultural inheritance. Even today people travel across the world to see some of the world’s most famous art. The Grand Tour still exists, if only in ghost form, as a gap year or a summer abroad. My granddaughter had her high school summer in Italy. The traditions continue. Such travel affords an education that books just cannot give.

In the 1960s, I accompanied my grandmother when she went back to the Old Country for the first time since she was five years old. We went to the village where she was born, Mosby, in southern Norway, and as part of that trip, I was sent on a (literal) Cook’s tour of Western Europe, taking in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France. I saw the Cologne cathedral, Notre Dame de Paris, Ste. Chapelle and the Louvre, among other things. Mostly, it made suburban New Jersey seem even more banal.

Met; Guggenheim; Frick; Whitney; Cloisters; MoMA

But then, I tried to escape the Garden State as much as possible. I was lucky: I had my own Grand Tour just a few miles away. During my own high school years, living on the Jersey side of the George Washington Bridge, I spent as much time as I could in Manhattan, going to concerts and visiting all the museums: The Met, the Guggenheim, the Frick, the Whitney, the Cloisters, the Asia Society, even the long-gone Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art on Columbus Circle.

And most of all — the Museum of Modern Art, where I felt most at home. I came to know many famous paintings as old friends. Van Gogh’s Starry Night; Matisse’s L’Atelier Rouge; Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon; Pollock’s One Number 31; Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie; Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy; Dali’s Persistence of Memory — all proper blue-chip Modern Art landmarks.

After I went away to college, I frequently made the trip to Washington, D.C., to visit the National Gallery of Art, and later, the Hirschhorn and Corcoran. I ate up art like a starving man. It’s hardly surprising that I later made my career as an art critic.

And working for the newspaper, I was sent around the country for major exhibits in Boston, New York, Chicago, LA, San Francisco, Seattle, Philadelphia. I was even sent to South Africa in 1989 to study the art scene there. And vacations brought me and my wife to France many times. Seeing as much as possible and finding troves of art in even small corners of the Continent.

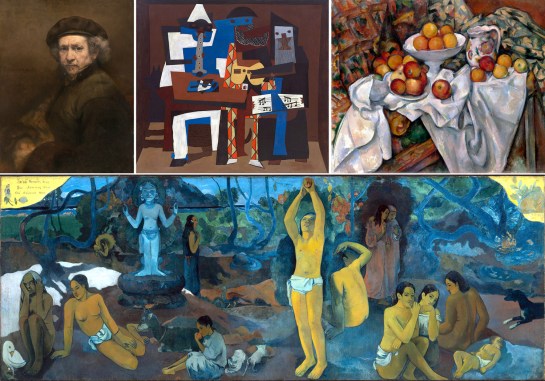

There have been dozens of important artworks I have been grateful to have known, not just in reproduction, but live, in front of my own eyes. My inner life is infinitely enriched by the experiences. There are many I could name, from Rembrandt’s self portrait in DC to Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Art We? Where Are We Going? from Boston, but I need to pick out at least these six as central to my understanding of art, and of life.

When you know works from reproduction, you cannot feel their size, cannot know the precise colors and pigments used, cannot grasp their tactile surfaces. Some of the most famous art in the world is known to most people by their reproduction on coffee mugs, T-shirts or commemorative plates. What you think is art is really just iconography — the nameable subject matter. The actuality, the physicality of the work is irrelevant in such cases. Seeing the original can then be a revelation.

So here are the six works that have meant the most to me, that I am most grateful for having been able to know personally.

Picasso, Guernica — When I was growing up, this, perhaps the greatest painting of the 20th century, was sitting in the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, and I visited it often. As a teenager, I knew it was “important,” because I had seen it in books and magazines. But I thought of it as “mine,” because I knew it would always be there for me. Alas, in 1981, it was repatriated to Spain, where, I have to admit, it belongs. An old friend moved away. It was the first important artwork that I had what felt like a personal relationship with.

Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles — In reverse, Blue Poles is a painting that came to New York for me. Pollock’s 16-foot drip painting from 1952 was auctioned off from a private collection in 1973 and sent to Australia. I loved many of the great Pollocks from MoMA and the Met, but thought I had lost the chance forever to see perhaps his most famous work. But a retrospective Pollock exhibit in 1998 at MoMA brought it back temporarily to the Big Apple. I got to see it there, where it was the jewel-lit highlight of the last gallery.

Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece — The giant altarpiece comprises 10 paintings by Matthias Grünewald, including the pathos-laden crucifixion as its centerpiece, and a group of polychrome wood sculptures by Nikolaus Hagenauer, executed between 1512 and 1516. It sits in the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar, Alsace, France. The altarpiece was designed to be either closed or open, with various panels showing at different times in the Catholic calendar. I have no stake in the religious significance, I cannot help but be overwhelmed by the pathos and power of the work.

Lascaux II — The cave paintings at Lascaux, France, date from about 20,000 years ago. They were discovered in 1963 and include about 600 images of prehistoric animals. The caves have been closed since 1963 to protect them, but a copy has been made and open to the public. I never thought I would get to experience them, but I got to visit both the reproduced experience at Lascaux II, but also the genuine cave art at nearby Font-de-Gaume. Seeing the original art there threw my spine into a buzz of uncanny deep-time — a state not rational but limbic.

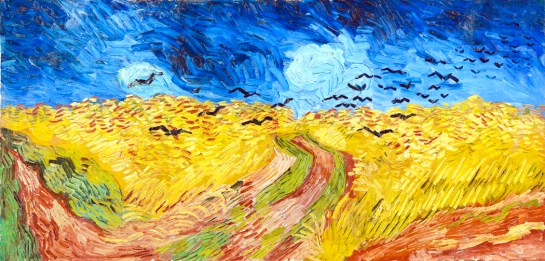

Van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows — In 1999 the LA County Museum of Art mounted a 70-piece show of the paintings of Van Gogh from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, including many of his most famous works. My job got me sent to cover the exhibit and I was blown over by the works (also, astonished at how amateurish and awful many of his early works were: It took a while for Van Gogh to become Van Gogh).

One of the last paintings in the last gallery was Wheatfield with Crows and up close you could see who wild and feverish the artist’s brushstrokes were, and what colors sat on his pallete, left largely unblended on the canvas.

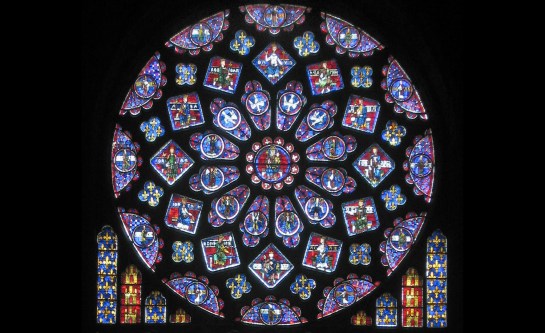

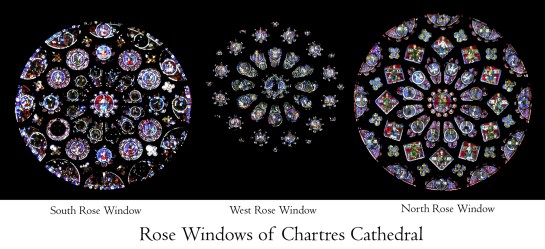

North Rose Window, Chartres Cathedral — I have been back to Chartres many times, and each visit, I spend a half hour, at least, sitting in the transept staring at the North Rose Window. It is, as I have said many times, the single most beautiful man-made creation I have ever seen. It is transcendent, a glowing object of meditation, whose shapes seem to move, to dance around the centerpoint. I am awe blasted. It almost makes up of all the misery, suffering and death human beings cause to each other.

This is, of course, a limited selection. Before writing, I made a list of paintings, sculptures, plays, operas, architecture, poems, novels — I could just make a list of the types of art that would already be too long to include in a single blog entry. Narrowing down to visual arts still left me with too many things to write about — hence my squeezing it all into only six works. (It tried to make a conventional 5, but I already feel bad about only including six.)

Seeing all this art and lamenting all that I never had a chance to see, only reinforced my sense that art is not just what makes us human, but how it makes us human.

I was talking with my very Southern wife about how those brought up down here have a stronger connection to the land than us Yankees. Southerners have often lived on the same patch of land for generations and their sense of identity can course back through great-grandparents and beyond. Your sense of who you are includes the centuries before you were born. New Jersey never gave me that.

But I do have that same sense when looking at the paintings or hearing the music of the past. This all gave birth to me; it is who I am. We too often think of culture in terms of hoity-toity high culture. But really, culture is all the things that have accumulated over time to make the lives we now take for granted.

When I see or hear the so-called canonical works of Western culture, I have that sense of belonging to a long, continuous line. It speaks to me; it tells me who I am.