I have traveled more widely than most, I believe. I was a travel writer for my newspaper (among other things). But even outside of vocational duties, travel has been central to my life. My late wife and I have been on the move considerably, visiting each of the 48 contiguous states many times, and gone outside the country when we could. In the summer of 1981, for instance, we put 10,000 miles on the car while driving around the country. We were both teachers and the summer gave us the chance to wander.

There are places, however, that I have gone back to, over and over, throughout my life, not through mere happenstance, but because they have been meaningful. They are destinations for non-religious pilgrimages.

Meaning can be hard to define. On first thought, one thinks “meaning” implies a second message: “This” means “that.” “I know what he said, but what did he mean?” That sort of thing.

But meaning has a more personal existence, a psychological one. Something can have meaning even if you don’t know what it means. I suppose you might otherwise call this significance. And there are places I visit over and over because they bear the weight of personal significance. They have meaning. And I go back to them.

Bodhgaya

It isn’t just me. The world is full of such places, some personal, some cultural, some religious or spiritual. They can be sacred spaces or holy ground. They have accrued some emotional hold on those for whom this kind of significance has meaning. It can be the Buddhist bo tree, the Dome of the Rock, the Western Wall, Independence Hall. For a few of us, the list would include Fenway Park. These are places of social significance and people will make the hajj to see them out of devotion or just to absorb the numinous halo surrounding them. Life is empty without meaning, although what we call meaning and where we might discover it is personal.

Meaningful places needn’t be so to groups, or to have religious importance. I have no belief in ghosts, spirits or ouija boards and I don’t believe that the past hangs on to the present to make itself palpable. But I have several times experienced a kind of emotional resonance when visiting certain famous sites.

Normandy beach

The thought re-emerged recently while watching the recent commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings in Normandy. I have visited those beaches and had an overwhelming rush of intense sadness. It was inevitable to imagine the thousands of soldiers rushing up the sands into hellish gunfire, to imagine a thousand ships in the now calm waters I saw on a sunny day, to feel the presence in the concrete bunkers of the German soldiers fated to die there manning their guns.

The effect is entirely psychological, of course. If some child with no historical knowledge of the events that took place there were to walk the wide beach, he would no doubt think only of the waves and water and, perhaps, the sand castles to be formed from the sand. There is no eerie presence hanging in the salt air. The planet does not record, or for that matter, much note, the miseries humans inflict on each other, and have done for millennia. But for those who have a historical sense, the misery reasserts itself. Imagination brings to mind the whole of human agony.

Perhaps I should not say that the earth does not remember. It can, in certain ways. Visiting the woods of Verdun in France, site of a horrendous battle in World War I, I saw the uneven forest floor, where time has only partially filled in the shell craters. Once the trees were flattened by artillery, leaving a moonscape littered with corpses. The trees have grown back, but the craters are still discernible in the wavy forest floor. The same child who thought of sand castles in Normandy might well think the churned land at Verdun merely a quirk of geology, but the land itself bears its scars.

The presence of the dead was overwhelming at Antietam, site of the bloodiest battle during America’s Civil War. In one spot alone, a 200-yard stretch called Bloody Lane, 5,000 men were blown apart in a few short hours.

Before Sept. 17, 1862, the brief dirt drive was called the Sunken Road, and it was a shortcut between two farm roads near Sharpsburg, Md. All around were cornfields rolling up and down on the hilly Appalachian landscape.

The narrow dirt road, depressed into the ground like a cattle chute, now seems more like a mass grave than a road. And it was just that when Confederate soldiers mowed down the advancing Federals and were in turn mowed down. The slaughter was unimaginable.

You can see it in the photographs made a few days after the battle. The soldiers fill the sunken road like executed Polish Jews. It was so bad, as one Union private said, “You could walk from one end of Bloody Lane to the other on dead soldiers and your feet would never touch the ground.”

It is difficult to stand now in Bloody Lane and not feel that all the soldiers are still there, perhaps not as ghosts, but as a presence under your boot-sole, there, as blood soaked into the dirt.

But it needn’t be horror or blood that gives meaning to a place. It may be achieved through personal association with something we lived through, or through esthetic appreciation — the sudden awareness of sublimity — or through an awareness of a less traumatic history born in a landscape. And I thought about places I have gone back to over and over; places that bear significance to me. I’m sure most of us could make such a list, whether long or short. Here are 10 of my personal pilgrimage sites that I have visited and revisited over a long life.

Walden Pond — I cannot count the number of times I have visited Concord, Mass., or how often I have made the pilgrimage to the glacial kettle lake just outside downtown where Henry David Thoreau built his cabin and lived for two years, and which led him to write his book about the experience.

The most recent visit was only two years ago, passing through on my way to friends in Maine. The site now has a large parking lot and a visitor center (although the parking is primarily for summertime local beachgoers, who use Walden Pond as a swimming hole). When I first saw it, there was not much there but the water and the woods; I had to park alongside the road.

I have circumambulated the pond, a walk of just under two miles, the first time in the early morning when a mist hung over the water and the sun slowly burned through. I have read Walden several times, and own several editions, both cheap and deluxe, and Thoreau’s other books, including his Journals, and eaten up his idiosyncratic style of writing with relish.

Walpi

Hopi Mesas — In northern Arizona, the Hopi have built their towns primarily on three mesas, First, Second, and Third, which are really the southern fingers of the larger Black Mesa. We have visited all three mesas many times, including one snowy Christmas spent with a Hopi family we knew on First Mesa in the village of Walpi. The warmth of the hearthfire in the stone house, and the cookies we were offered, and the smiles on the faces of the children are indelible.

Another time, we were invited to a social dance on Second Mesa in Old Oraibi, and climbed to the roof of one of the houses with the rest of the Hopi to watch and cheer the Kachina dancers. Another time, driving past New Oraibi, at the foot of Second Mesa, we were caught as traffic was halted so the sacred Kachina dancers could cross the road from where they emerged from the kiva and marched toward the plaza. We were not supposed to be there but couldn’t leave, with the Kachina traffic cop in front of us and several cars behind. We apologized profusely, but the angry cop didn’t seem to care. We shouldn’t have been there, but we also couldn’t have known a sacred dance had been scheduled for that day.

You can stand at the cliff edge on First Mesa and look south over the Navajo Reservation, nearly to Flagstaff and marvel at the intense beauty of the Colorado Plateau.

Chartres Cathedral — It wasn’t until our second visit to France that we managed to get to Chartres, but after that we went back over and over. The cathedral is, of course, a World Heritage Site, and a sacred place to many. But it spoke to me less of religion than of history — architecture 800 years old and still functioning for its original purpose.

Most of the cathedrals and basilicas of Northern France have been restored and reworked (Notre Dame, before the fire, was largely re-imagined in the 19th century as it was restored by Viollet-le-Duc) but Chartres is almost entirely original. If you are sensitive to it, you can feel all that passage of time embodied in the stonework and the interior space.

The cathedral sits at the top of a hill at the center of town, and can be seen in the distance from miles around. I have spent hours sitting in the transept meditating over the great north rose window, which remains the single most beautiful manmade object I have ever seen. The entire experience engenders awe.

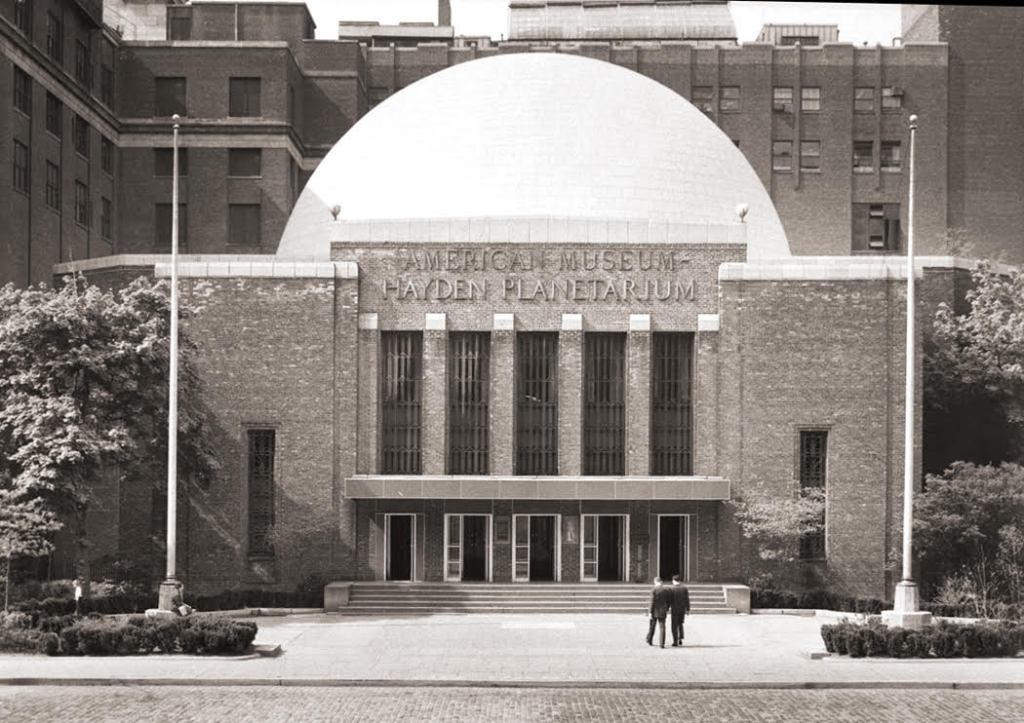

American Museum of Natural History — I was originally going to list New York City here, but then narrowed it down to Manhattan, but, really, the center of magic for me is the Natural History Museum. I first visited on a third-grade school trip and fell in love with the dinosaurs. But all through my childhood and adolescence I visited the museum as often as I could. I loved the dioramas, the dinosaur bones, the giant stone Olmec head, the huge suspended blue whale — even the “Soil Profiles of New York State.” To say nothing of the room full of chunks of quartz, each with a little typed tag explaining where it was collected.

I could also have mentioned the George Washington Bridge, which my grandfather helped build; he was an engineer working on the bridge in the 1930s. Through most of my life, when living in or visiting New Jersey, I would take the bus to the bridge and walk across the bridge to 178th St. I have walked the bridge too many times to count.

The Outer Banks — I went to Guilford College in North Carolina beginning in 1966 and soon met lifelong friend Alexander and we made annual camping trips to Cape Hatteras, usually in winter when the beaches were empty. Later, my first wife and I spent our honeymoon camped directly under the lighthouse. It was February and the regular campsites were closed, and so we pitched our tent in the dunes.

I have been back over and over, with each succeeding wife or possl-q, although as I got to be old, we tended to sleep in motel rooms. When my brother began teaching in Virginia, he lived at the northernmost bit of the Outer Banks, Sandbridge, and when visiting I often made a side-trip back down to Hatteras and Okracoke.

Once, with Alexander, we went after a huge storm, and parts of the road were washed out just north of the lighthouse. He got out of the car and walked in front, feeling the asphalt under his feet and leading me safely past the overwash. Another time, at night, we walked down to Cape Point with a Coleman lamp projecting our shadows, like giants, up into the misty black sky.

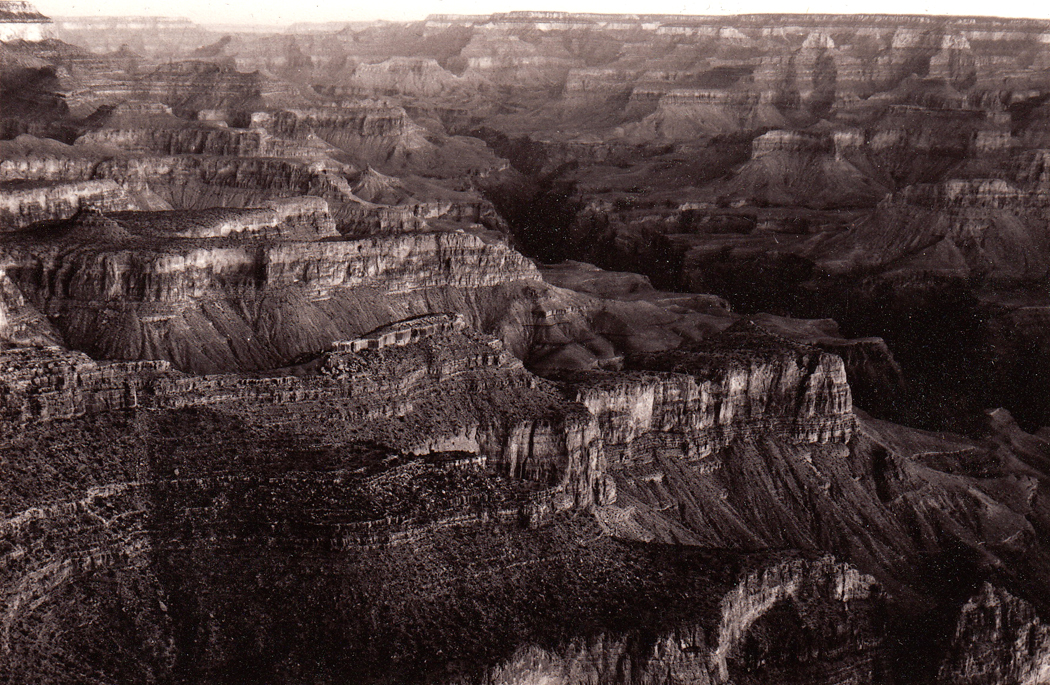

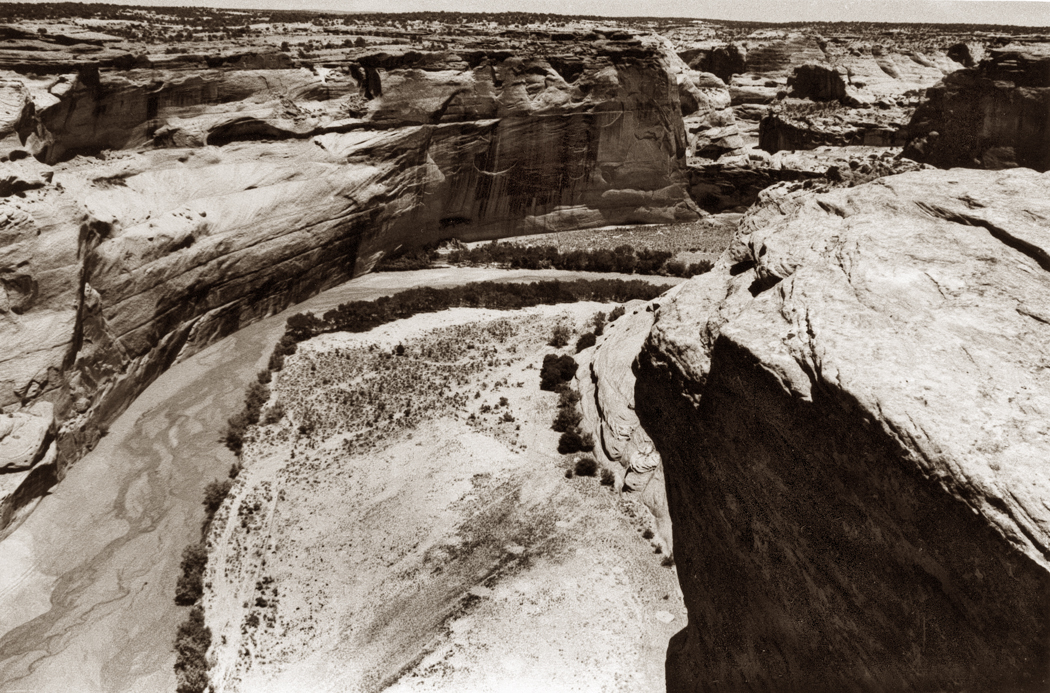

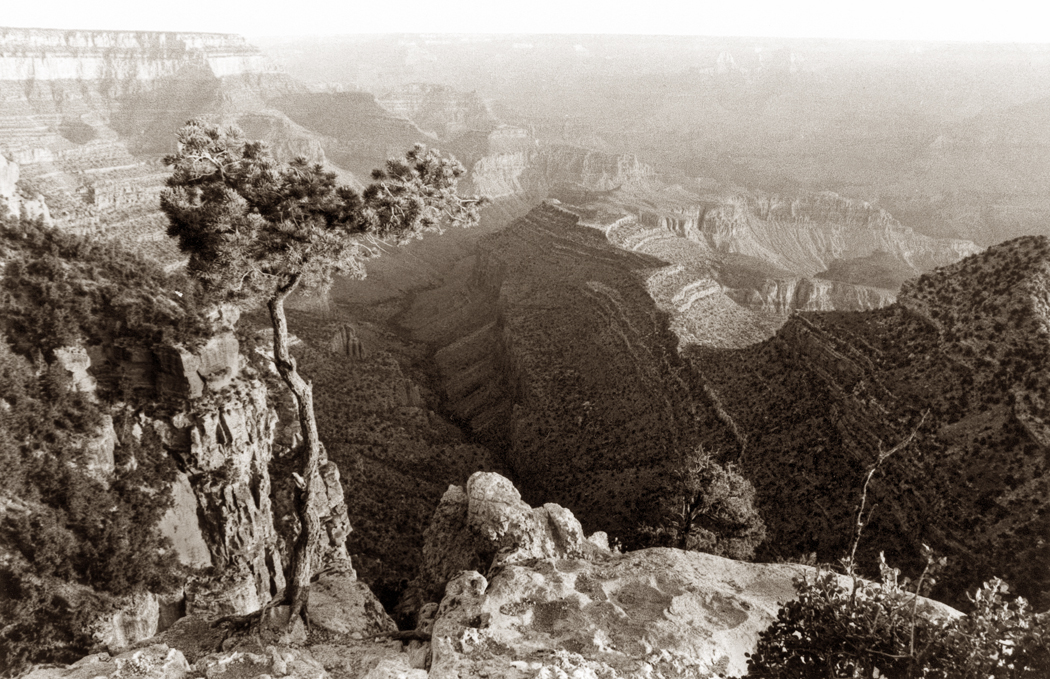

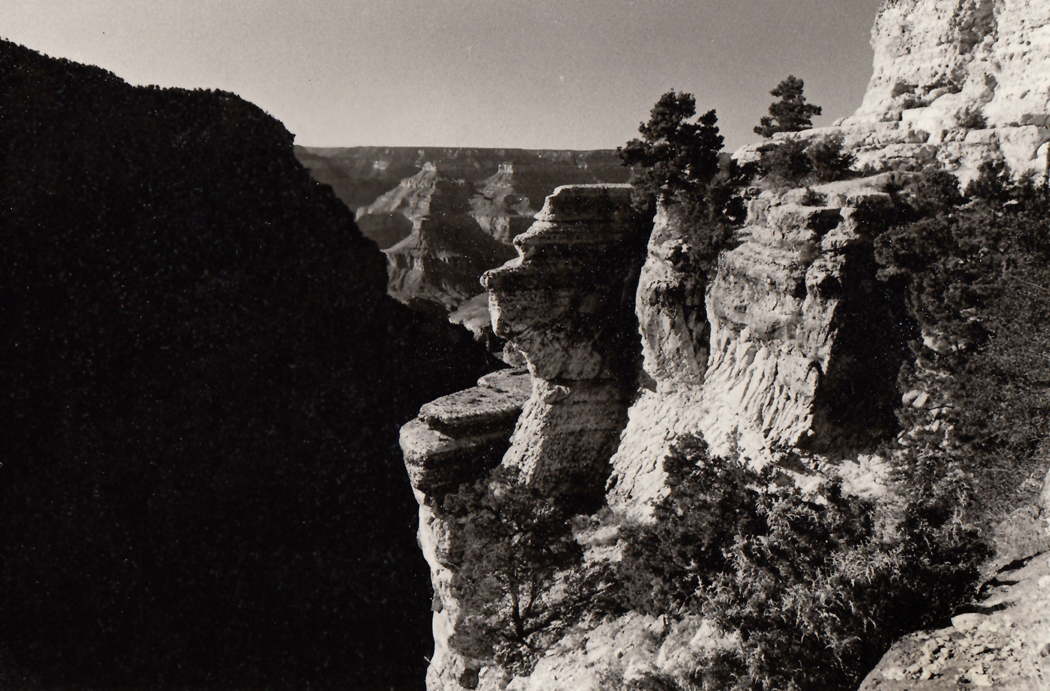

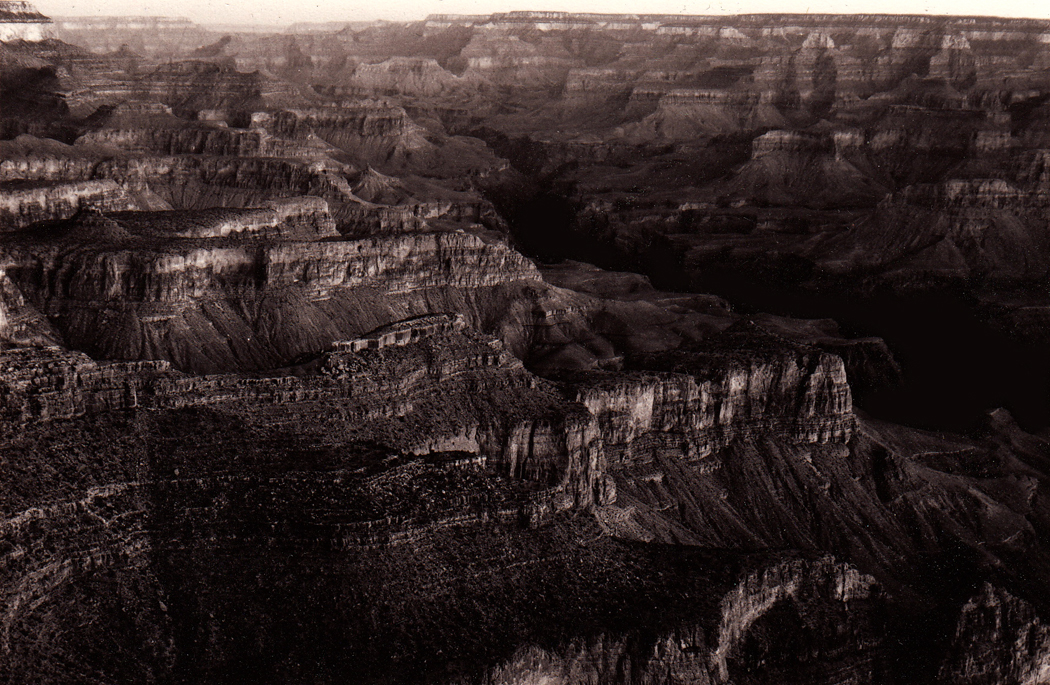

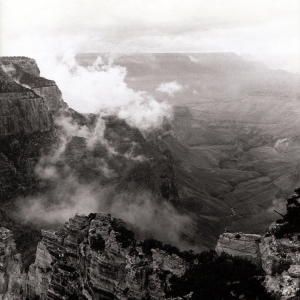

Grand Canyon — My brother once observed that unlike most hyped destinations, where you are always at least a tiny bit disappointed when you finally get there, the Grand Canyon is actually more impressive, more overwhelming, when you actually see it live: It never lets you down. It is 200 miles of vast geology, color, and depth.

We lived in Arizona for 25 years and so I cannot number the times we visited the Canyon, mostly the South Rim, where most of the tourist action happens. But the second time we came, in 1982, we went to the North Rim and when we couldn’t get a room at the hotel there (it is always full), we went out of the park after dusk into the national forest, where it is legal to camp anywhere, and pulled into a side road in the dark. In the morning, we got out of the tent and discovered that if I had backed the car up 10 feet further, we would have tumbled down into the canyon. We were right on the edge.

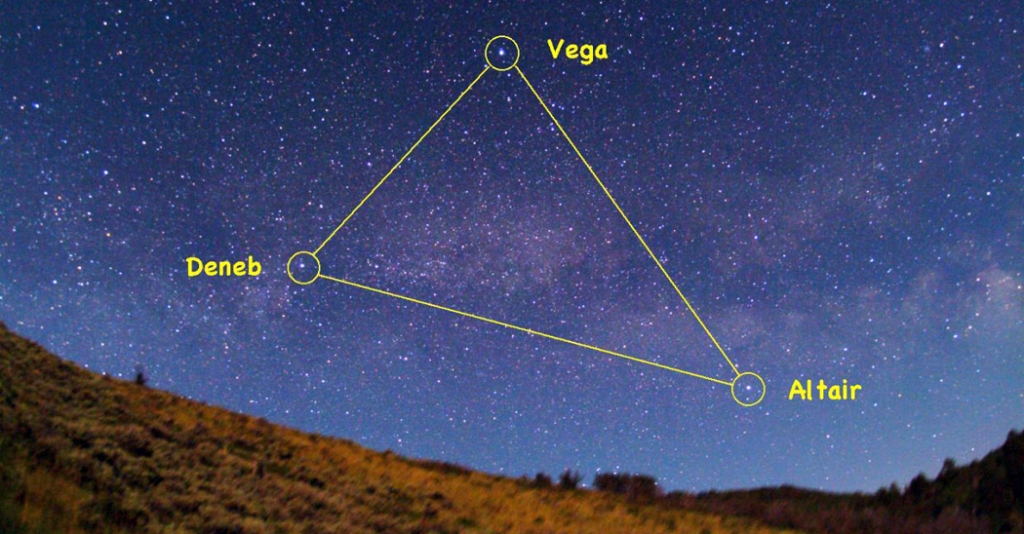

And once, on assignment from the paper, I drove 60 miles off road to the Toroweap Overlook, also on the North Rim, but in pure wilderness where only a rare person ventures, and camped away from all city lights, where the night sky was neon in intensity.

Hudson River Valley — I grew up in northern New Jersey, in the apotheosis of suburbia. But my father’s family had a rustic house — a “bungalow” — in West Park, N.Y., halfway up the Hudson River, and we spent many summer vacations, and at least one winter ski vacation, at the bungalow. It was the town where the once-famous nature writer John Burroughs lived. There was woods, a swimming hole with a waterfall.

But up and down the river, from Dunderberg through Bear Mountain and the Seven Lakes Drive, it was the escape from the ordinariness of the suburbs. We regularly went swimming in the summer at Lake Welch, or watched ski jumping at Bear Mountain.

In 1986, we drove up Perkins Drive to the top of Bear Mountain, during an outbreak of gypsy moth caterpillars. The tower at the top was covered in a sheath of hairy worms and the ground was gooey with the squashed ’pillars. It was eerie and more than a little stomach churning.

The bungalow at West Park

The Nilsen family drove up Route 9W on summer weekends to visit the bungalow, and the three-lane highway had to curl around Storm King Mountain, a section of road that made my cautious father extremely nervous with a sheer drop down the edge to the river. They are gone now. That portion of 9W has now been re-routed and the treacherous third (middle) lane now long gone. Near Haverstraw, the “Ghost Fleet” of WWII-era liberty ships were moored. They are gone now. So is the bungalow. I am sorry for that.

From the Palisades up through the Catskill Mountains, the Hudson River is holy ground, as far as I am concerned. It glows with the inner light of myth.

Schoodic Point — Maine is its own mythology, and like the city of New York, I was going to include the whole state in my list, but likewise, I have narrowed it down to the place that I have been back to over and over for the longest. I first visited Maine as an infant when my parents took a trip there. I can’t say I have any memory of then. But subsequently, I have been there many times, now to visit my friends Alexander and Mary Lou. I’ve traveled the whole state over, camped at Mt. Katahdin, driven round Mooselookmeguntic Lake, reached the summit of Cadillac Mountain on Mt. Desert Island, took the tour of the paper mill in Millinocket — and you can get there from here.

But the mythic center of Maine for me has been the rocky bit of coastline that juts out into Frenchman’s Bay north of Acadia National Park, called Schoodic (with the double “O” pronounced as the “oo” in “good.”) It is one of those windswept romantic landscapes where the spume blows into your face, the waves crash against rock with an explosive boom, and the sky, water, and land still seem of one substance.

Giverny — I’ve been to Monet’s house and gardens three times, once in the spring and twice in the fall. He and his family lived in the small town 50 miles north of Paris, from 1883 until his death in 1926, and many of his greatest works were made there, primarily his extensive series of water lily paintings.

I had become familiar with some of those wide canvases in museums in New York and at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. And I had been inspired to make scores of photographs of waterlilies in imitation of Monet’s paintings.

But the chance to get to see the genuine article in situ, in the grand gardens in Giverny was a pilgrimage from the get-go. One enters, of course, with curiosity, but also with reverence.

Austin house

Rock Castle Creek, Woolwine, Va. — Some of the happiest and unfettered moments of my life have been spent on the porch of the Austin house along Rock Castle Creek in Virginia. I have been back many times, beginning during my college years, when a group of Guilford students hiked the five or so miles up the creek, fording over logs, and reaching the 1916 farmhouse, with its spring house and barn.

With my companion, or with a group, we would break into the house (not recommended, for legal reasons) and roll out our sleeping bags on the floor. At night in the summer, the field in front of the house was a galaxy of blinking lightning bugs.

At the end of Bergman’s film, Wild Strawberries, the old professor Isak Borg, lies in bed after a tumultuous day, full of cares and regrets, and in voice over, says, “If I have been worried or sad during the day, it often calms me to recall childhood memories,” and he thinks of a time he saw his parents together, with his father fishing. It soothes him and he sleeps peacefully. For me, that moment of pure calm happiness that I recall is of sharing a hammock with my beautiful red-headed mate on the second floor porch of the Austin house and watching the sun go down over the creek and meadows beyond. Such moments consecrate a place.

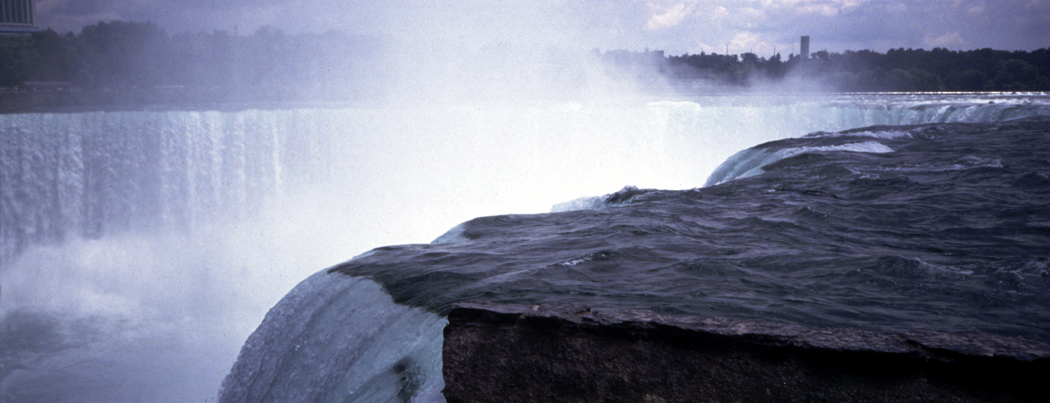

These are all places I have gone back to multiple times. But there are places where I have only ventured once that still have that emotional buzz that signifies a sacralized locale. These may be places set aside by history or by personal experience, or simply by their extraordinary natural setting.

We all have such places, and they while they may be widely shared, such as the World Trade Center, they are just as often special only to one or a few people. Places where we stand in awe, and may not even be able to speak.

From top right: Cape of Good Hope; Gaspe; Montauk; Finisterre

For me, many have been where the land runs out and the seas begin. There is something about the extremity, the sense of the limitations of land and the seeming infinity of the watery horizon. I seek them out, such as the Gaspé Peninsula, Long Island’s Montauk Point, Brittany’s Finisterre, or South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. At my age, I know my existence shall soon run out and the dark infinite void is the horizon, and that I will not likely ever get to visit such places again.

And I have been to Civil War sites where I felt the ghosts in the soil: places such as Shiloh, Vicksburg, Appomattox, Gettysburg, Petersburg, Bull Run, Chancellorsville, Fredericksburg, and Five Forks. And important places in the Western expansion: Sand Creek, Little Bighorn, Wounded Knee, Washita. Japanese internment camps at Manzanar and Poston. And to the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where Dr. King was shot; and the slave quarters at the Oakley Plantation in Louisiana. All places where death and suffering are felt in the air breathed there — at least to anyone with an awareness of history.

Mt. Saint Michel

And I could list many less fraught places with their own resonance that I have only visited once, but that have created space in my psyche: Mt. Saint Michel; Big Bend National Park; the catacombs in Paris; the caves at Lascaux; the town of Moosonee on James Bay in Ontario; the Okefenokee swamp in Georgia; Mt. Angeles in Washington’s Olympic Mountains; Hallingskarvet mountains in the spoon of Norway; Chaco Canyon; Taliesin in Wisconsin; Ice Water Springs in the Smokies; the Salton Sea; Glacier Bay in Alaska.

Each of these places has become a part of me. They are my sacred spaces.

Click any image to enlarge