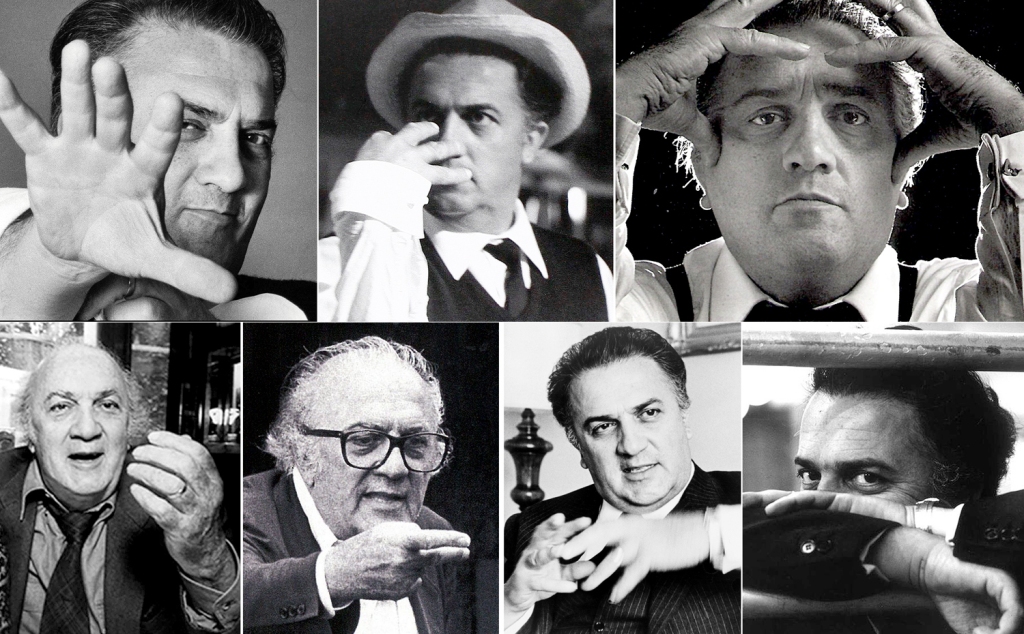

Federico Fellini is unquestionably one of the greatest of all filmmakers. He is on everyone’s list. He won five Oscars, was nominated for a total of 17 of them. Heck, he was nominated twice before he even made his first film (as screenwriter for two Rossellini films). He made two of the movies on my own 10-Best list.

His 1954 film, La Strada, changed my idea of what movies could be. When I was growing up, the movies I saw, mostly on TV, were filled with car chases and gunfights. Movies were an entertainment. But, in my college film series, I saw La Strada and realized, for the first time, that film could be about real things, and that they could leave me weeping. The final scene with the brutish Zampano (Anthony Quinn) on the beach, wailing for what he knew he had lost, left me drained.

And La Strada isn’t even one of the two Fellini films on my 10-Best.

There are only a few film directors who have words added to the dictionary defining their style, but we all know what “Fellini-esque” means: an almost surreal grotesquerie tied to a very personal sense of human psychology. There are other great filmmakers, but there is no “Scorsese-esque,” no “Renoir-esque,” although these directors, too, had a personal style. Only two directors have joined the dictionary, with “Fellini-esque” and “Bergmanesque.” The two directors couldn’t be more different, but their styles are each identifiable, even when another filmmaker uses them.

So, Fellini’s is a distinct and individual voice. Yet, the arc of his career is also distinct, and not toward ever greater or more profound films. It is a career with an upward start, a middle as high as it gets, and then a slacking as he declined. What is interesting is that it is that the cause for both up and down is the same: Fellini being Fellini.

Federico Domenico Marcello Fellini was born in 1920, two years before Mussolini’s rise to power, in the Adriatic city of Rimini. His father was a salesman and hoped his son would rise to be a lawyer. And although he enrolled in law school, Fellini’s biographers says that “there is no record of his ever having attended a class.” Instead, he dropped out to become a cartoonist and caricaturist, and he wrote for several satirical magazines.

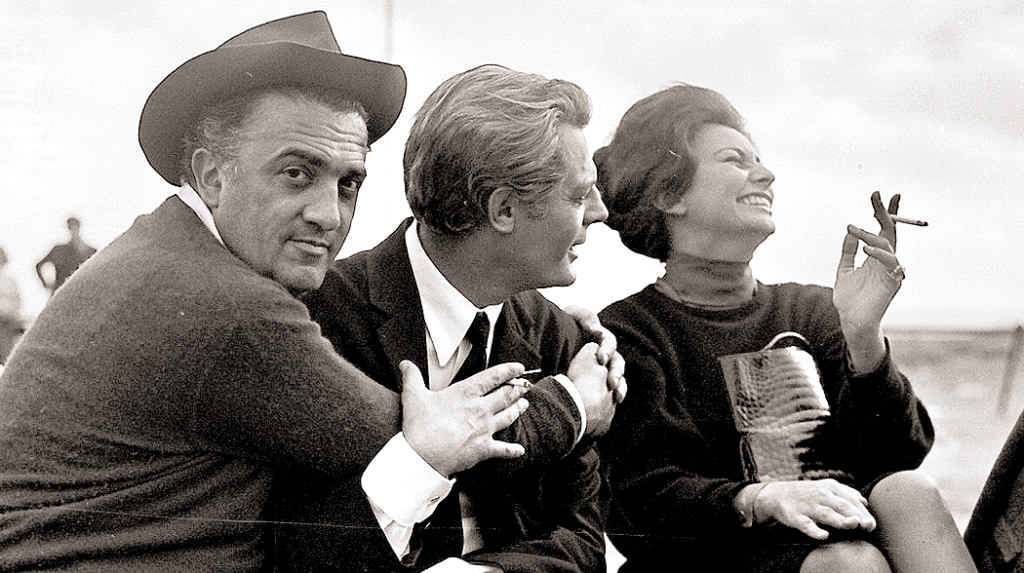

He expanded to writing gags for radio shows and managed to avoid the Italian draft during the early years of World War II. He also met his wife and muse, radio actor Giulietta Masina (they remained married from 1943 to his death in 1993).

His work in radio brought him to the attention of Neo-Realist film pioneer Roberto Rossellini, who hired him to work on the script of Rome, Open City (1945) and later, Paisan (1946). Both efforts won him Academy Award nominations.

In 1950, he got to direct his first film, Variety Lights, followed the next year with The White Sheik, two low-budget comedies of middling success and reputation. But then, in 1952, he got to make the first genuine Fellini movie, I Vitelloni (“The Young Bulls”, or, idiomatically, “The Layabouts”), an autobiographical Neo-Realist film about his own teen years in Rimini, which won him a fourth Oscar nomination for screenplay. (The film wasn’t released in America until after the success of La Strada and Nights of Cabiria, — both Oscar winners for Best Foreign Language Film — hence, the later nomination.)

These three early masterpieces — I Vitelloni, La Strada and Nights of Cabiria — all have their roots in Italian Neo-Realism, although with Fellini’s particular stamp of both humor and grotesquerie. There is no confusing them with films by Rossellini, De Sica or Visconti. While each of Fellini’s first great films concern themselves with social conditions, poverty and the Post-War problems, they are really more concerned with individuals. Fellini was never overtly political.

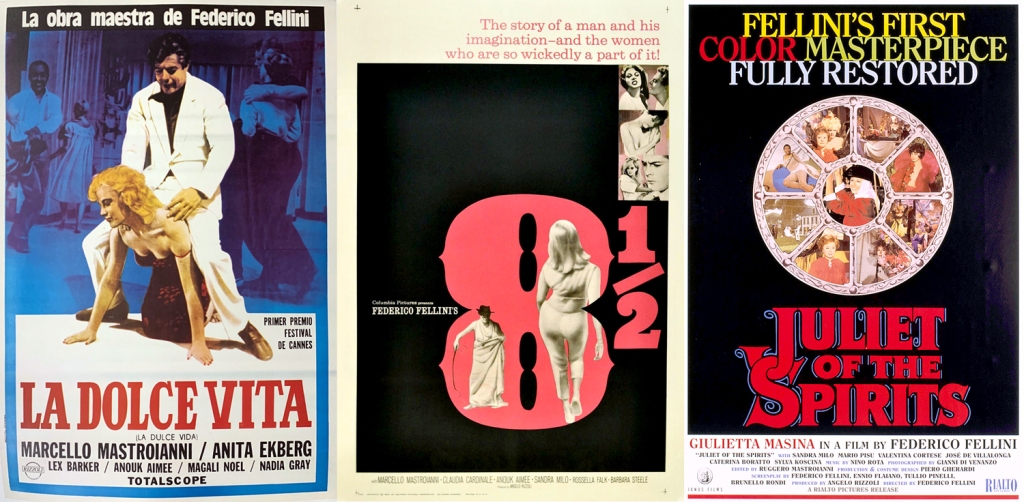

Fellini had, by 1957, been nominated for six Academy Awards and won two. But they could not have foretold what came next. Arguably his greatest film, La Dolce Vita, was also his greatest box office success.

The great 1960 Italian classic of the Roman “sweet life” in the postwar years shows us nine days and eight nights in the life of tabloid celebrity journalist Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni) as he negotiates personal relationships, professional crises and spiritual doldrums.

“Rarely, if ever, has a picture reflected decadence, immorality and sophistication with such depth,” Box Office magazine said when the film was released. Rather than a plot, the film is a collection of episodes as our hero recognizes the emptiness of his life, decides to do something about it, and ultimately, cannot. The final scene with Mastroianni on the beach, shrugging at the girl across the way as a sign of giving up, is one of the most heartbreaking ever shot on film.

Fellini structured the film in a series of climactic nights each followed by a dissolving dawn. In each of the nighttime episodes, Marcello faces one of his demons — although he doesn’t recognize them as such. Each night rises to a crux, a point that might waken Marcello to the aimlessness of his life, and at each sunrise, there comes not a culmination, but a dissipation of the situation — all its air is let out.

La Dolce Vita occupies a pivotal point in the career of Fellini, between the early Neo-Realist films, such as I Vitelloni and La Strada, and his later, sometimes visionary films. In La Dolce Vita, there is a balance between the sense of external reality — Italy’s boom economy in the decade after World War II, and its forgotten underclass — and the purely subjective sense of individual psychological crisis.

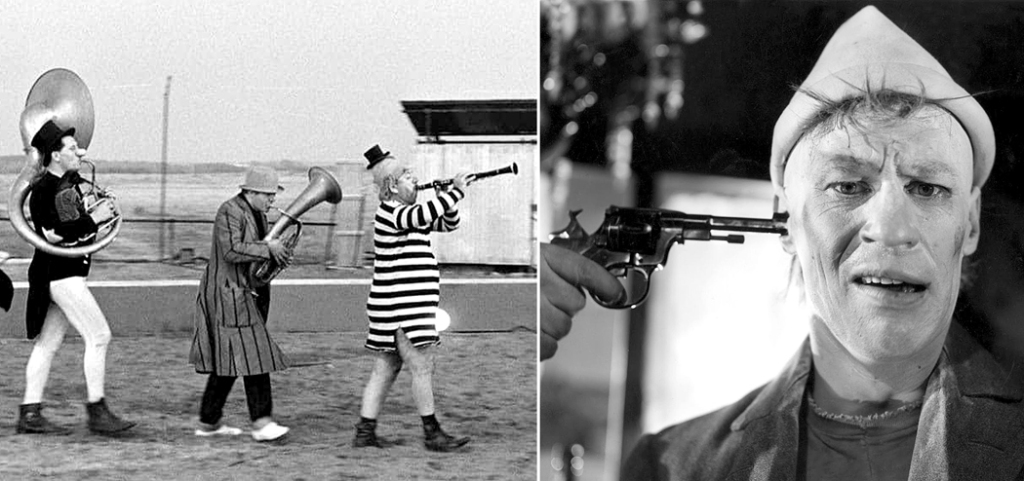

In his next film, the crisis becomes personal: Otto e Mezzo or “8½” is about a filmmaker who can’t figure out what to do next. It begins with one of Fellini’s most visionary scenes: The filmmaker (again played by Mastroianni) is stuck in his car and imagines being trapped, then floats away above the car, held only by a kite-string attached to his ankle. As an opening scene, it would be hard to match, let alone beat. Through the rest of the film, he attempts to avoid his responsibility, to his producer, to his wife, to his mistress, to his crew, to his financial backers, to his fans. He imagines committing suicide, and in the end, in one of the most enigmatic and memorable scenes ever, joins a dance to the circus music of Nino Rota. As a concluding scene, it would be hard to match, let alone beat.

What does that scene mean? We all have our own solutions. I tend to see it as the same message that Krishna gave to Arjuna in the Bhagavad-Gita, that the end or the meaning isn’t the point. The doing is. Joining in life is the point of life. Or as writer Joseph Campbell once phrased it, “the joyful participation in the sorrows of the world.”

Whatever you decide about the ending, it is clear that these two films, together, are among the highest points of film art, at the same time, clever, funny, moving, heartbreaking, hugely cinematic and visual, and ultimately, wise.

There are grotesque scenes in La Dolce Vita and Otto e Mezzo, but they are just part of the mix. In some of his later films, such as Roma or Fellini Satyricon, the grotesque predominates. But at the midpoint of his career, in his two best films, he balances the real and the freakish like a saint balancing heaven and hell.

Then, Fellini discovered Carl Jung, read the psychiatrist’s autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, began visiting a psychoanalyst, experimented with LSD, and became fascinated with dreams, archetypes, spirits and the unconscious. He famously defined a movie as “a dream we dreamt with our eyes open.” Jung is a dangerous thing put in the hands of an artist with no governor on his engine.

Fellini made Juliet of the Spirits in 1963, about a repressed housewife (Masina) entering a world of debauchery, visions, memories, and mysticism to find herself. It was Fellini’s first full-length color film, and uses what one critic called “caricatural types and dream situations to represent a psychic landscape.”

As critic Roger Ebert wrote, “The movie is generally considered to mark the beginning of Fellini’s decline.”

And three of the next four of Fellini’s major films are given over to grotesquerie, hallucination and oneiric excess: Fellini Satyricon (1969), Fellini’s Roma (1972), and Fellini’s Casanova (1976). The fact that the director’s name is attached to these three titles should tell you something. There is nothing historical or documentary about them: They are exudations of the filmmaker’s fevered brain.

Satyricon is the best of the three films, and actually captures rather accurately the spirit of Petronius’ First Century tale of Nero’s Rome. Although Fellini invented most of the episodes, they capture the tone of the picaresque original pretty well.

Satyricon, Roma and Casanova all prominently feature parades of caricatural grotesques, people buried under exaggerated make up and hairdos, rather like some of the more peculiar drawings of Leonardo da Vinci.

Even if they don’t succeed as whole works of art, each is stuffed like a cannolo with brilliant imagery, unforgettable moments. It is as if he was more concerned with the moment-by-moment, than the story coherence — the way a dream moves. “Don’t tell me what I’m doing,” he said. “I don’t want to know.”

If La Dolce Vita and 8½ were satires on modern mores, the later films pass beyond satire to a rather personal misanthropy dredged up from his unconscious.

There was one very bright and beautiful exception, though, a final grace note to his career — the 1973 film, Amarcord, which is a comic, forgiving and joyful reminiscence of Fellini’s childhood in Rimini. In 1953, his I Vitelloni explained why the young Fellini desperately wanted to escape his provincial hometown; twenty years later, he felt the need to show what he had lost by leaving. Everything that he was bitterly satirical about in his earlier films becomes the very human qualities of his dramatis personae in Amarcord. It is a gentle, affectionate, humane account of human folly, and the easiest of all of Fellini’s films to love.

He made a handful of films after that, but none catches fire. There was Ginger and Fred (1986) and, more dubiously, City of Women (1980) in which Fellini, as his frequent alter ego Marcello Mastroianni, attempts to deal with his fear of, and lack of understanding of — women.

Fellini made his last film, The Voice of the Moon, in 1990, and died of a heart attack in 1993, a day after his 50th wedding anniversary, and just a few months after receiving his Oscar for lifetime achievement.

As is so often the case, Fellini’s best and worst were manifestations of the same thing — his ability and his need to put himself into his films. As he once said, “Even if I set out to make a film about a fillet of sole, it would be about me.” It gave him the secret of breaking out of the Neo-Realist mold and find his own way, but it also let him wander off into a sometimes almost solipsistic dream world of images and obsessions. When focused, as in La Dolce Vita and 8½, he was one of the three or four greatest filmmakers of all, and even when he was noodling in fevered Fellini-Land, still provided indelible visions and emotions. There was no one like Federico Fellini.

_____________________________

We are not in control of our memories.

One doesn’t own one’s memories.

One is owned by them.

—Federico Fellini

______________________________

I used to have long discussions with friend and colleague Sal Caputo, who was pop music critic for the newspaper I worked for. Sal — or Salvatore — was as Italian in ancestry as I was Norwegian. And it played out in our conversations. Sal was always intense and expressive, and sometimes prone to anger and moods. He took things personally when I didn’t — I always remembered the line from Renoir’s film, Rules of the Game: “The terrible thing about life is that everyone has their reasons.” I.e., it isn’t personal.

Searching the Internet for Sal, I could only find a couple of mug shots

Anyway, we once had a talk about movies and our varying takes on Federico Fellini and Ingmar Bergman. It wasn’t about which was the better filmmaker, but about how we internalized the films. We both appreciated both directors. But there was a difference.

The difference was almost comic. Consider the ways each director portrayed clowns. In 8½, they play Nino Rota’s music and point the way to salvation for our lost Marcello; in Bergman’s Sawdust and Tinsel, well, you get the picture.

I loved Fellini’s films and could appreciate both the filmmaking craft that went into them, and also the humanistic concerns of the director. Fellini rates very high on my list of movie directors. Top three or four. But somehow, I always feel as if I’m watching him from the outside. In contrast, when I see a Bergman film, it is in the blood — I know this world from the bones out. It is a world I didn’t just see, but lived.

And for Sal, it was quite the opposite: Fellini felt to him like home, like everything he knew and felt in the fibers of his nervous system.

In Bergman, all the action is internal; his characters are all suffering midnights of the soul. Their torture is self-imposed.

While Fellini’s people have trouble with other people, with society, with Catholicism, with Fascism, with their wives.

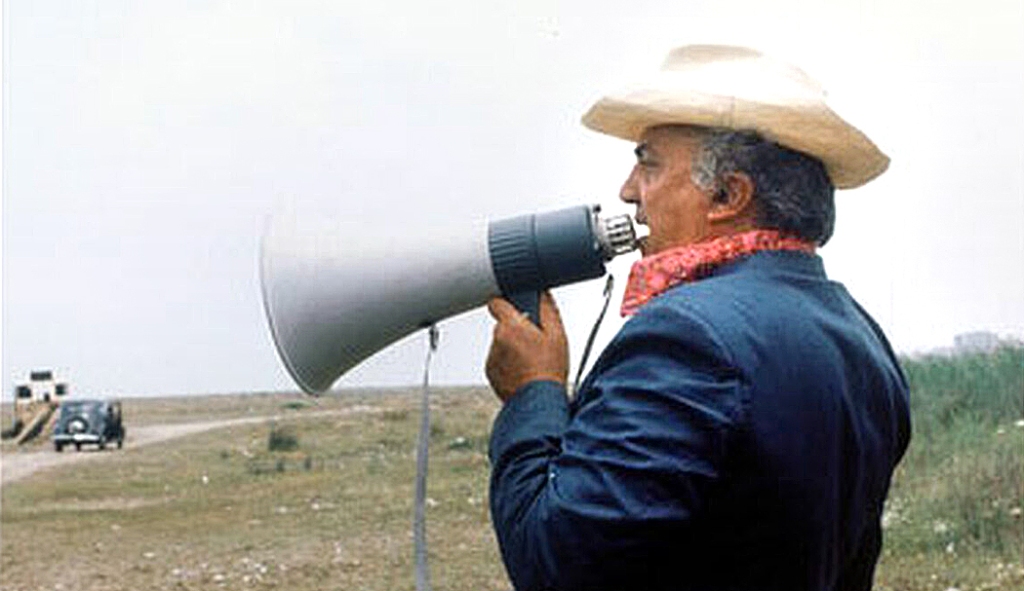

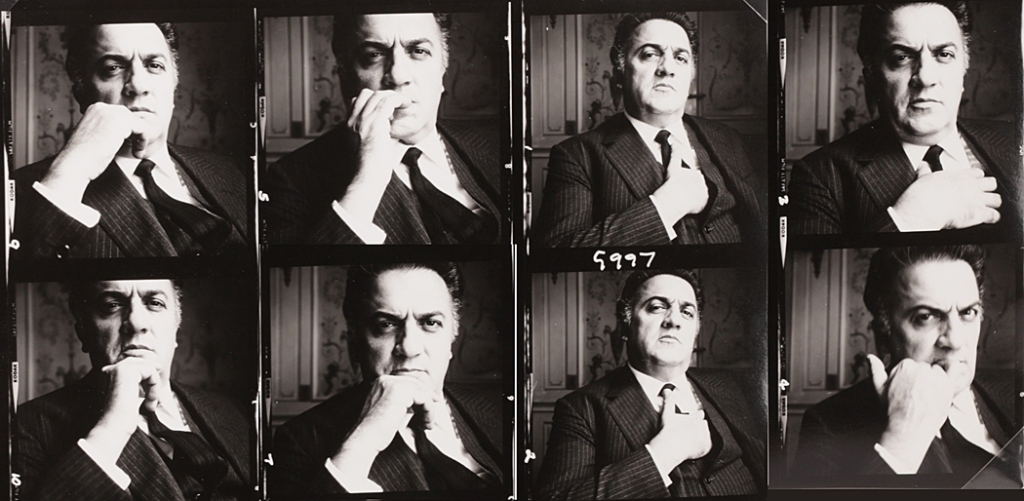

Bergman’s people sit silently, brooding. Fellini has hardly a photo of himself without his hands waving in the air, expostulating.

This sense of recognition in the films, different for Sal and for me, has always made me wonder if there is something genetic about national difference. All the Squareheads I know feel Bergmanesque and all the Italians seem to feel Fellini-esque. This may just as easily have grown out of cultural familiarity as from DNA, and I’m not sure its origin makes a difference.

I’m cheating a little with these images — not all German painting is so dour, or Italian so extravagant — but only to make a point. But there are national and regional styles, psychologies, approaches and techniques that show up across the arts. German painting is instantly told apart from Italian painting. French music from Viennese. Russians have their novels; Italians their opera; Iberians their fado and zarzuealas.

You can hear six bars of Elgar, Holst or Vaughn Williams and you know they are English.

This has been recognized for centuries. In Baroque music, national styles were standard descriptions, as Bach’s French Suites or his Italian Concerto, or his Overture in the French Style. And you could never confuse Telemann’s music for Vivaldi’s or either for Couperin’s.

(In deliberately oversimplified terms, German music emphasizes harmony and counterpoint; Italian music emphasizes melody and singing; French music emphasizes timbre and ornament.)

And there does seem to be a generalized North-South axis. If you compare the Gothic cathedrals of northern France with those of Italy, you see a spare austere style, even with all the statuary, and in Italy or Spain, a kind of Plateresque extravagance.

In the European south, expression seems to be extrovert and unrepressed; in the north, introvert and brooded over. It would be wrong to say that Italians are more emotional than Scandinavians. But in the north, the emotions are directed at themselves, whereas in the south, they are almost theatrical.

So far, I’m using European examples, but this national or folk identity is global. Chinese art is instantly identifiable. And except for those examples of conscious imitation, Japanese art is very different. Hindu sculpture on the Indian subcontinent is easily told from Buddhist sculpture in Southeast Asia.

Nor, in Africa, could you confuse a Benin bronze with a Fang mask or a Kota reliquary figure.

These differences are not merely stylistic, but grow from very different world views and historical experience. There is a world of difference between the Tlingit of the rainy Northwest Coast of North America and the Navajo of the desert Southwest.

Many years ago, I was first made aware of this kind of difference when I moved from New Jersey to North Carolina and discovered a culture radically alien to the one I was brought up in. It was agrarian rather than suburban; it held a tremendous grudge from the previous century that had not made a twinkle of a dent in my Northern psyche. It had a sense of history tied to the land, whereas I grew up in a world of second- and third-generation immigrants. These kinds of cultural differences make their way into the art, whether it is the difference between Hemingway and Faulkner, or between Fellini and Bergman.

It may be only a metaphorical expression, but it is profound: It is in the blood.