Is there a more over-hyped piece of art than the Mona Lisa? I don’t intend to demean Leonardo’s painting, but to question the PR. It’s an excellent painting, but I could name a hundred others as good or maybe better. Yet, this portrait of a middle-class Florentine woman is the most widely known painting in the world. At least, since 1911.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was the prototype of the Renaissance Man. Initially a painter, he was also an inventor, scientist, sculptor and architect. But he was also a world-class procrastinator and leaver of unfinished works. His attention span could be intense, but often quite short.

He was born to an unmarried woman about 20 miles from Florence, Italy. His father was a local notary who married four times and sired at least 17 children, including our young Leo.

He studied painting as an assistant to Andrea del Verrocchio, but then made his living primarily as a military architect, working in turn for the Sforzas, the Medicis, and Borgias. In his spare time, he continued to take painting commissions (not all of which he ever finished) and working on various scientific and philosophic theories.

“Leonardo painting the Mona Lisa” by Cesare Maccari (1863) mistakenly has the left-handed artist painting right-handed

When he was 51, living back in Florence, he was commissioned to paint a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, who was married to Francesco di Bartolomeo del Giocondo. She married him in 1495, when she was 15 years old, which meant she was about 23 when Leonardo began painting her. (I say “began” because the painter never really finished the painting and never delivered it to its commissioner; he never received payment for the commission, either).

The painting has long been known, outside of the English-speaking world, as La Gioconda, or “the Cheerful Woman,” but was also just the feminine version of her married name, Lisa del Giocondo.

“Lady with an Ermine;” “Ginevra de’ Benci;” La Ferronnière”

Leonardo seemed to enjoy including puns in his portraits. La Gioconda comes from the Latin “jocundus,” which means agreeable or pleasant. Hence the mild smile. In his three other portraits of women, he does something similar. The Lady with an Ermine includes the beast because the ermine was a symbol of the Sforza family, and also because the sitter’s surname, Cecilia Gallerani — mistress of Ludovico Sforza — is a play on the ancient Greek name for an ermine, galê (γαλῆ). The portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci sets the sitter among Juniper plants. “Ginevra” is Italian for Juniper. And finally, La Belle Ferronnière, is an early portrait of Lucretia Crivelli, who was married to an ironmonger (“ferronnier”) and mistress of Francis I of France. In her portrait, she is also wearing a decorative headstrap known as a “ferronniere.”

The better known title, Mona Lisa, is her name, Lisa, and the honorific “Mona,” which is a contraction of “Ma Donna,” or “My Lady.” In Italian, it is there usually spelled “Monna,” and the painting as Monna Lisa. (Never “Mona,” because in various Italian dialects that is a slang word for a woman’s lady parts, and used as an insult for a stupid or obstructionist person, much as the C-word is used in British English, where it doesn’t bear quite the taboo status it has in the U.S.)

Leonardo seems to have worked on the portrait until 1506 and put it aside for a bigger commission, a mural commemorating the Battle of Anghieri — a mural he never finished, either. He kept the painting through several moves and took it to France with him in 1516, where he began working for King Francis I, primarily as a military engineer. The king bought the Mona Lisa, probably in 1518, and it wandered around various palaces after that, until after the Revolution when it found its way to Napoleon’s bedroom and then to the Louvre.

“Mona Lisa” and what it might look like under the darkened varnish

Or, at least, that’s the most likely story. There is an alternative version, in which the painting, of an unknown sitter, was commissioned by Giuliano de Medici in 1513 and was later confused for the Giocondo painting that was mentioned by historian Giorgio Vasari.

The problem is complicated by the fact there are two Mona Lisas, both generally accepted as by Leonardo — a second one that was in the possession of Leonardo’s assistant (and likely lover) Andrea Salai and catalogued after Leonardo’s death in 1519.

Making matters worse, there are at least three Mona Lisas that experts agree were made in Leonardo’s studio, at the same time, with the extras likely painted by either Leonardo himself or his assistant Salai.

Prado “Mona Lisa” before and after restoration

One of the supernumeraries is at the Prado in Madrid. It was discovered when a portrait of a lady, with a black background was cleaned in 2012 and the background of the famous Mona Lisa was uncovered. The previously ignored painting was then studied more closely and found to have been painted in Leonardo’s studio at the same time as the more famous painting.

“Isleworth Mona Lisa” and Louvre version compared

Another version, hidden in a Swiss bank vault until 2012, is the so-called Isleworth Mona Lisa, which was first discovered in 1913 and held in private hands since then. Originally brought to England from Italy in the 1780s by a Somerset nobleman named James Marwood and listed in his collection as “La Jaconde.”

Examined by hordes of connoisseurs, experts, scientists and historians, it has been confirmed as a Leonardo original, as an obvious copy, as the first true Mona Lisa, as a later copy by Leonardo himself, or by one of his assistants, and maybe with a few corrective brushstrokes by the master himself. In other words, it has been argued over constantly and no true consensus has been arrived at.

It differs from the Louvre painting by having a different background landscape, being painted on canvas and not on poplar board, showing an obviously younger subject, and having columns on each side of the image.

It does date from the right era, all are agreed, and may have come from Leonardo’s atelier. Since there is further confusion over the date of the initial painting — either begun in 1503, as per Vasari, or in 1513, as per Louis d’Aragon — perhaps the Isleworth Mona Lisa was painted first and years later, the Louvre painting was made; or perhaps the other way around. Not to dive too deep into the weeds here, but X-rays of the Louvre painting show considerable work, changes of pose and features, while the Isleworth painting seems to show very little, suggesting that the Louvre painting came first, with all the hedging and shifting, and the Isleworth version was a confident copy. Perhaps. Who knows?

It was not unusual, for Leonardo, or any other painter at the time, to make more than one version of a painting, so it is possible that both were made by our hero. Perhaps. Who knows?

Top row, L-R: two 16th c. copies; 2 18th c. copies, 1 19th c. copy; bottom row: copies with columns, various eras

We do know that the painting was copied many times over the centuries. Some copies have the columns, others do not. A sketch made by Raphael in about 1505 shows the columns, but perhaps Raphael painted it from memory, or from hearing a description. It is not a very faithful copy, either way.

There are also a series of nude Mona Lisas, seeming to emanate from Leonardo’s studio, perhaps by his students. There are at least six of them. Their grasp of female bodies seems somewhat sketchy, so they may have not been painted from life, but imagined by students less familiar with actual women. (Michelangelo had a similar problem with female nudes, often making them look like male body builders with odd lumps of fat on their chests). In fact, there is some speculation that the subject was not Lisa del Giocondo, but Leonardo’s assistant and gay lover Salai, painted as a woman. Mona Lisa in drag? Perhaps. Who knows? These paintings are usually titled Mona Vanna.

It is the Louvre Mona Lisa that has become the de facto true one, and has been copied, discussed, parodied and referenced endlessly. It is a fairly standard Renaissance-era portrait pose, three-quarter length. There are four aspects of the painting that stand out.

First, the eyes, which are said to “follow you around the room,” as if that were some magical power. Any face painted or photographed with its subject looking directly out will have eyes that seem to look at you, no matter what angle you stand in front of it. There is no trick to that. But in addition, our lady has no eyebrows and no eyelashes. Many of the copies do, and Vasari describes her eyebrows particularly, and so it is assumed they used to be there, but were accidentally wiped off during some previous cleaning of the painting.

Then, there is the mouth and its ambiguous smile. The Mona Lisa smile has been subject of innumerable New Yorker cartoons, popular songs and magazine ads. A slight upturn at the corners of the lips, described only by a tiny gradation in shading. This has also been lauded as a special and unique quality of Leonardo’s genius. Of course, many other paintings of the time display nuanced expressions also.

And there are the hands, gently overlapping in a demure pose meant to signify breeding and chastity. Although one critic, making an argument for the Isleworth Mona Lisa as the original, complained that the hands of the Louvre painting are “thick and bloated.” The eyes of the beholder, I guess.

Salient features of “La Gioconda”

Finally, there is the landscape behind the sitter. It has never been satisfactorily identified as a real location, and, of course, it doesn’t have to be. Fantasy landscapes abound in art history. But one theory, which I have long agreed with, is that it isn’t meant to be a real piece of geography at all, but is a tapestry on the wall behind La Gioconda.

When Leonardo painted the Mona Lisa, oil painting was still relatively new to Italy. It had been common in northern Europe for at least a century, but most Italian painters stuck with egg tempera. Leonardo was one of several who picked up the new technique, which allowed a more graceful shading of tones and colors.

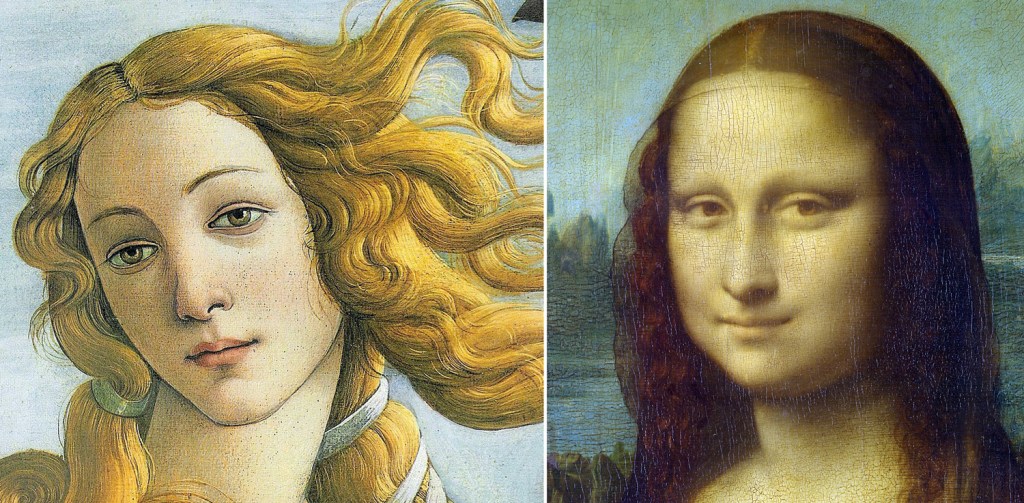

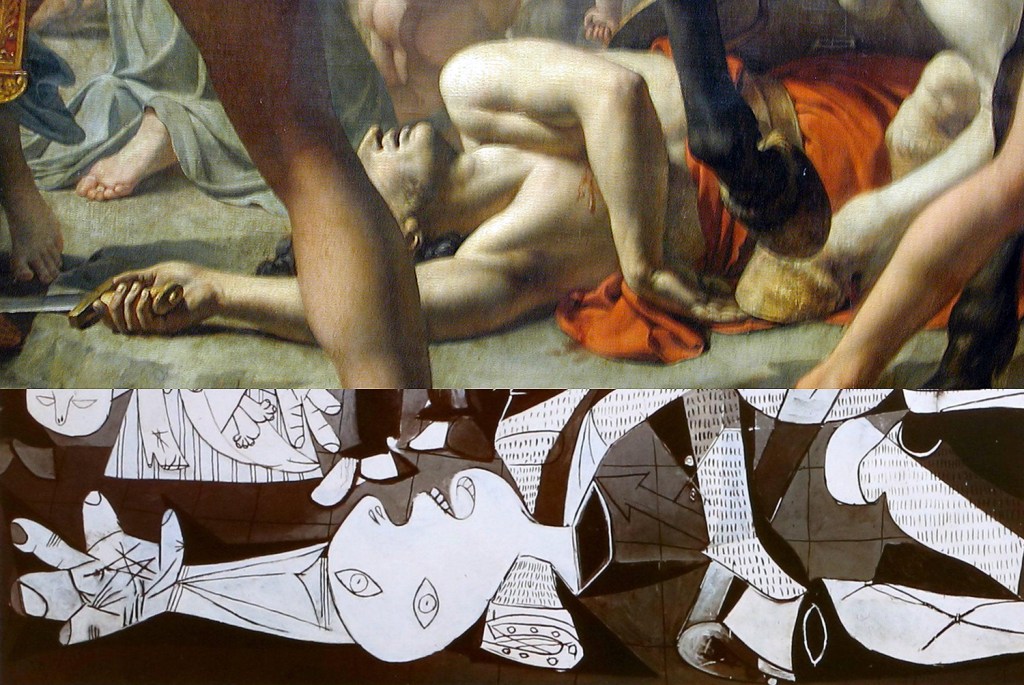

You can see the difference if you compare Botticelli’s Venus with Leonardo’s Gioconda. Edges are clean and distinct with tempera, but less so with oil, and the particular technique Leonardo used, called “sfumato,” or as he described it: “without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke.”

It was shadows, he said, that build up volume and bring grace to faces. “The gracefulness of shadows, smoothly deprived of every sharp contour.”

In his studies of human perception, the scientist Leonardo had come to the conclusion that human vision is not the clear-edged thing that shows up in tempera, but something more soft-edged, and he sought to capture that in his work. There are few lines or edges in the Mona Lisa; it is mostly soft, in diffused light.

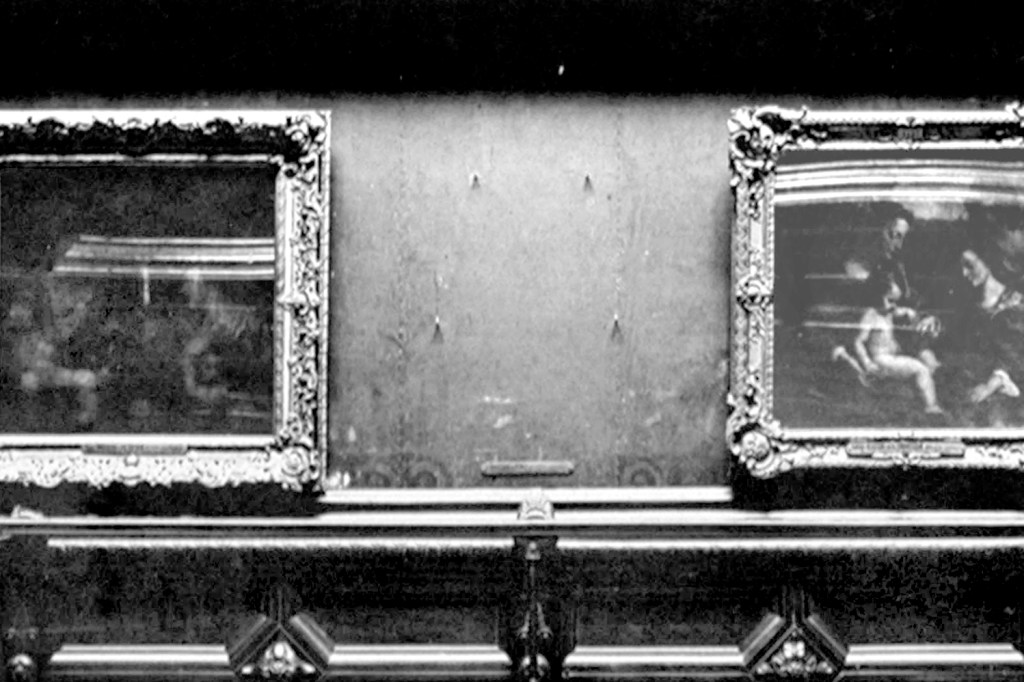

This is how important the Mona Lisa was at the Louvre in 1911

But back to 1911. I mentioned 1911 earlier. Before that year, the Mona Lisa was just one of a bunch of respected portraits of women in the Louvre. Most of them were Madonna and child paintings. Visitors to the museum were much more likely to line up to view the Venus de Milo or the barn-size expanse of Veronese’s Wedding at Cana (32 feet wide). Our Mona Lisa was just another frame among all others hanging on a gallery wall.

Then, on August 21, it wasn’t. Instead, there were four hooks where the painting had once been attached. The theft of the Mona Lisa became international news. Daring art theft!

The painter Louis Béroud had come to the museum that morning to paint a scene of the gallery, with its paintings, and reported to the guards that where the Mona Lisa should have been, there were only those hooks.

The guard assumed the painting had been removed by conservators to clean or photograph. But soon, when they went to check, it became apparent that the painting was gone. The museum was closed for a week while they searched high and low. No luck.

Vincenzo Peruggia mug shot

The painting was gone for more than two years. Turns out, it spent that time in the rented room of an Italian immigrant, hiding in a cupboard only two miles from the Louvre. Vincenzo Peruggia had been working as a glazier at the museum on and off, and felt, as an Italian patriot, he should return the patrimony of his native land. He grabbed the Mona Lisa primarily because his other targets were too large to smuggle out of the museum.

The police searched for the painting furiously, and many rumors abounded, leading to false leads.

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported how early interest was centered on Bordeaux, and indeed, Canadian newspaper the Ottawa Free Press on 26 August 1911 reported from Paris how “there appears to be no doubt here that Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous painting Mona Lisa, was taken to Bordeaux, whence it is feared it will be carried either to Spain or South America.” According to its account, a witness had seen a “stout man, carrying a large panel covered with a horse blanket, take the 7:47 express for Bordeaux on Monday morning,” soon after the Mona Lisa was taken.

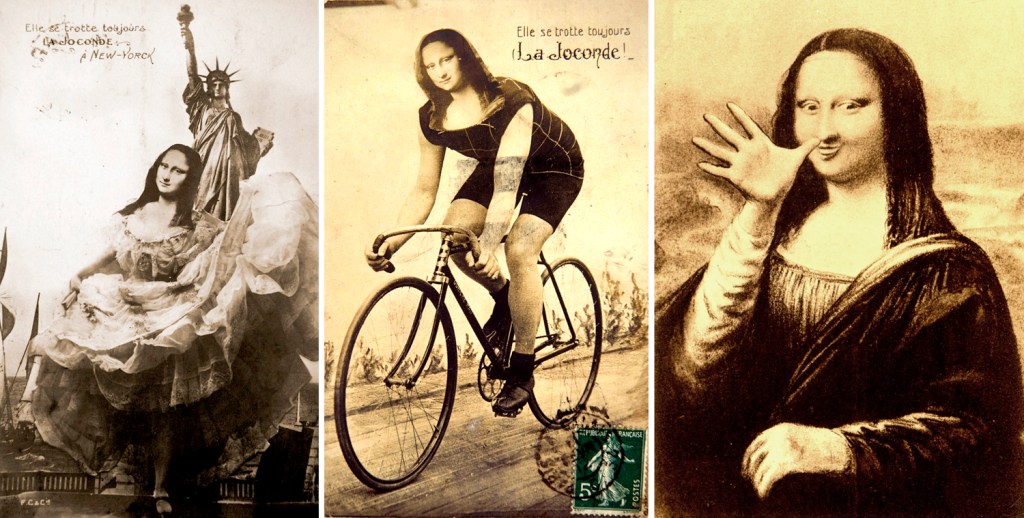

Of course, that was fake news. But stories sold newspapers. One newspaper printed an “interview” with Mona Lisa. Another that fictional criminal Arsène Lupin must have done it. There were movies and popular songs about it. Over two years, hundreds of phony leads were sent to police.

Various people were arrested and released, including Pablo Picasso. Picasso, and his friend Guillaume Apollinaire had been dabbling in some minor fencing of stolen artwork. But they were soon cleared in the Mona Lisa heist.

French postcards: Where is she?

Actually, the painting didn’t leave Peruggia’s cupboard until he tried to sell it to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, where he was arrested and served seven months in prison — a short term, since, in Italy, he was considered a patriot.

But the Mona Lisa was not one of the many “appropriated” artworks that have found their way into various museums around the world. It was sold quite legally to the French king 400 years previous. By 1914, it was returned to the Louvre.

Today, the painting is safely protected behind bullet-proof glass and a barrier, so that the closest anyone can get to it is some 10 feet away, and that only if they are lucky, seeing as how the painting attracts an average of 30,000 visitors a day — about the size of the crowd at an average major league baseball game. People are not there to see the painting, so much, as to be able to say they have seen it. There is little chance to study the vaunted brush work or sfumato.

The protection is certainly warranted. In 1956, it was attacked with acid and also with a rock thrown at it. In 1974, it was red paint. In 2009, a coffee cup. In 2022, a man in drag in a wheelchair threw a cake at it. And on January 28 this year, two members of the Riposte Alimentaire (foot retaliation) sprayed pumpkin soup at it, demanding sustainable farming. What the Mona Lisa has to do with farming is anyone’s guess.

This year it was decided to create a special gallery just for the Mona Lisa, in the museum basement, and to charge a special admission fee, and run controlled groups past the painting, in an attempt to systematize the current chaos. Whether this happens or not, we’ll have to wait to see.

The Mona Lisa is no longer just one painting in the Louvre. It has morphed from a painting into a meme.

More on that in Part 2

Click on any image to enlarge