Every once in a while as if by a miracle, something good is transformed by art into something godawful. Case in point: the most recent remake of the detective stories of Georges Simenon that go under the heading “Maigret.”

The Belgian writer pumped out (and that is about the only way you can describe his method) some 75 novels and piles of short stories featuring his creation Jules Maigret, commissaire of the police judiciaire at le Quai des Orfèvre in Paris.

I just tried watching the new Maigret series on PBS Mysteries and, honestly, someone needs to be shot before a firing squad. They seem to have turned Maigret and his team into “Le Mod Squad.” Simenon’s Maigret is famously middle aged and looks like a tired bureaucrat. That’s how Simenon wrote him. To turn him into a — and I quote — “young, streetwise leader of an elite crime unit known as ’The Maigrets’” — is worse than a travesty, it is pandering of the worst sort.

“Le Mod Squad” hardly ridicules it enough. “Montmartre 90210” perhaps — No pipe, no hat, no overcoat. Probably doesn’t even drive a Citroen. And that curated day-old chin scruff — what a tired cliche! And from the images I’ve seen online, the series seems to be lit in the contemporary flat digital style, with faces darker than the background. Oy veyzmir.

In other words, I don’t think I’ll be watching this series. I could barely make it through the first episode. In fact, I couldn’t. The episode was a two-parter and I quit after the first part.

Its sins are legion. Perhaps if it had been made under some other title, like “Les Flics a la Mode,” it might have served a purpose on network TV, alongside long running series. Maybe even “CSI: Paris.” But its questionable status as a remake of the famous French detective is not its only or worst sin. Its dialog is straight out of a soap opera, with great lumps of exposition floating like unincorporated lumps of flour in a gravy. The script seemed assembled rather than written.

It’s not that I object to modernizing or updating a classic. Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat did a great job with the BBC’s Sherlock, with Benedict Cumberbatch, keeping all the quirkiness but adding a digital world. But the new Maigret is simply ham-handed.

Simenon wrote his Maigret books from 1931 until 1972, which were only a fraction of his immense literary output. Right from his apprenticeship, writing under 17 pen names, he produced 358 pulp novels and short stories from 1921 to 1934. He was writing at a pace of 70 typed pages a day. Even after he began writing under his own name, his production was prodigious. There can be no count, only approximations. Estimates have run from 170 books to about 500. What is more amazing is the quality level. No less than Andre Gide wrote, “I consider Simenon a great novelist, perhaps the greatest, and the most genuine novelist that we have had in contemporary French literature.”

Simenon’s mysteries are functionally different from the standard model, where, as in Agatha Christie books, suspects and clues pile up and at the end, Miss Marple sorts it all out and solves the crime. With Maigret, we often know who the perpetrator is in the first few chapters and the bulk of the book is Maigret figuring out how to catch the bad guy, or what motivates him and could lead to his capture. The heart of a Maigret book is not the mystery, but the characters and their psychologies. It seems almost as if Simenon begins with a vivid character or two and builds a story around that. We read them not to find out “whodunnit,” but to spend time with fascinating personages.

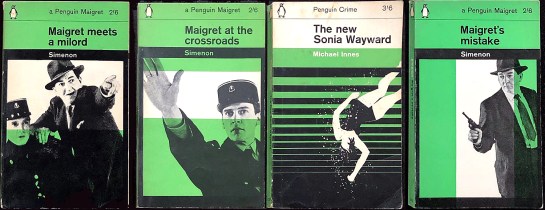

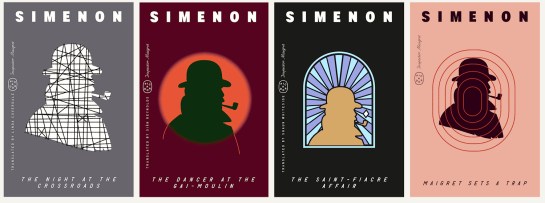

All of his Maigret novels remain in print — the whole series in English translation is published by Penguin Books. Numerous other translations are available, and multiple compilations.

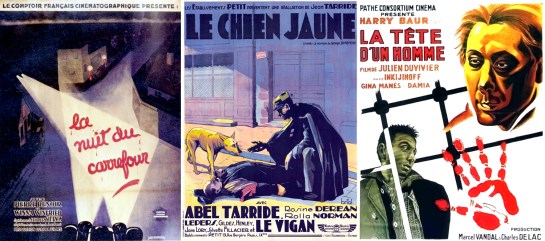

At least 70 films and TV series have been made from his works, beginning with Jean Renoir’s La Nuit du Carrefour, from 1932, starring the director’s brother Pierre Renoir as Maigret. The same year saw Le Chien Jaune (“The Yellow Dog”), with Abel Tarride as the commissaire, directed by his son, Jean Tarride. The following year, Julien Duvivier directed Harry Baur as Maigret in La tête d’un homme (“A Man’s Neck.”)

Over the years, at least 35 actors have smoked the pipe as Inspector Maigret, give or take some forgotten versions. They were made in several languages, including Italian, German, Russian, and Japanese.

Albert Prejean, Michel Simon, Jean Gabin

But most notable, in English or French, including three films made with Albert Prejean as Maigret in the mid-1940s, by a wartime German film company in occupied France; and another three, from 1958 to 1963 with Jean Gabin. The great Michel Simon took his turn in 1952 in one-third of the anthology film Brelan d’as. Maurice Manson played him in Maigret dirige l’enquête (1955).

And Gerard Depardieu was an especially bulky commissaire in Maigret (2022). The prolific (and prodigious) French actor had previously played a Maigret clone in 2009’s Inspector Bellamy.

Charles Laughton, Richard Harris

English language one-offs begin with Charles Laughton in The Man on the Eiffel Tower (1950), and Richard Harris, in a tweed hat, in Maigret (1988), of which, the less said, the better.

Rupert Davies

But, when you have 75 novels and 28 short stories to draw from, the ideal version of Inspector Maigret is a television series. The first — 53 episodes from 1960 to 1963 — featured Rupert Davies, who would have been the ideal Maigret except for the fact that the episodes were only 50 minutes long, and the production was rather studio-bound (other than some excellent exteriors actually shot in Paris). Standard TV lighting and sets.

Jean Richard, Michael Gambon, Bruno Cremer

Jean Richard starred in 88 90-minute episodes from 1967 to 1990, and was the version Simenon said he liked best. Bruno Crèmer filmed 53 episodes from 1991 until his death in 2005, each 90 minutes long. These are probably my favorites.

Michael Gambon gave what might be the definitive English language version in only 12 episodes from 1992 and 1993. Although each episode was only 50 minutes, he embodied Maigret so perfectly, at least for an English-language audience, that his successors all pale in comparison.

And those include Rowan Atkinson in four 90-minute versions from 2016 and 2017. Atkinson (aka Mr. Bean) does a very good job, but the filmmakers attempted to turn the books into noir films, mostly shot at night or in moody rain, and dumped so much dialog, they were almost silent films. The Maigret books are almost pure dialog, very like the earliest Dragnet episodes.

I have not seen the Dutch versions, first with Kees Brusse in 6 episodes from 1964; or 17 episodes with Jan Teulings from 1966-1969. Nor the Italian version with Gino Cervi from 1967-1972. And not the 25 episodes in Japanese with Kinya Aikawa from 1978, where the inspector’s name is transliterated as “Megure.” “Meg-goo-ray.” I’m not sure where any of these might be found.

And that leaves us with the latest misery, a poor substitute for the real Maigret.

Simenon

L’Envoi

Georges Simenon was as much a character as those he stuffed into his novels. His writing was prodigious — those hundreds of novels — but so was his sex life. He was one astonishing horn dog.

When he married, the pair took on a young housemaid, and by the evening of her hiring, Simenon had already had sex with her. This went on for some time. His wife seems to have become inured to his proclivities, which included frequent visits to brothels.

When his wife went away for a spell, he hired a second maid. Same result. When his wife finally left him, everyone moved up a notch. Later a third maid took over from the second, in a kind of musical beds. Although beds are not really the issue. One report has him coming home one day and seeing his maid washing dishes, and then coming up behind her, lifting her skirts, having his way while she continued the scrubbing.

He once claimed to have had sex with 10,000 women, although his second wife, Denyse, said, “Georges always exaggerates. We worked it out ourselves once and it came to no more than 1,200 women.”

How strange, then, that Jules Maigret was so faithful and attentive to his wife, Louise — aka Madame Maigret.