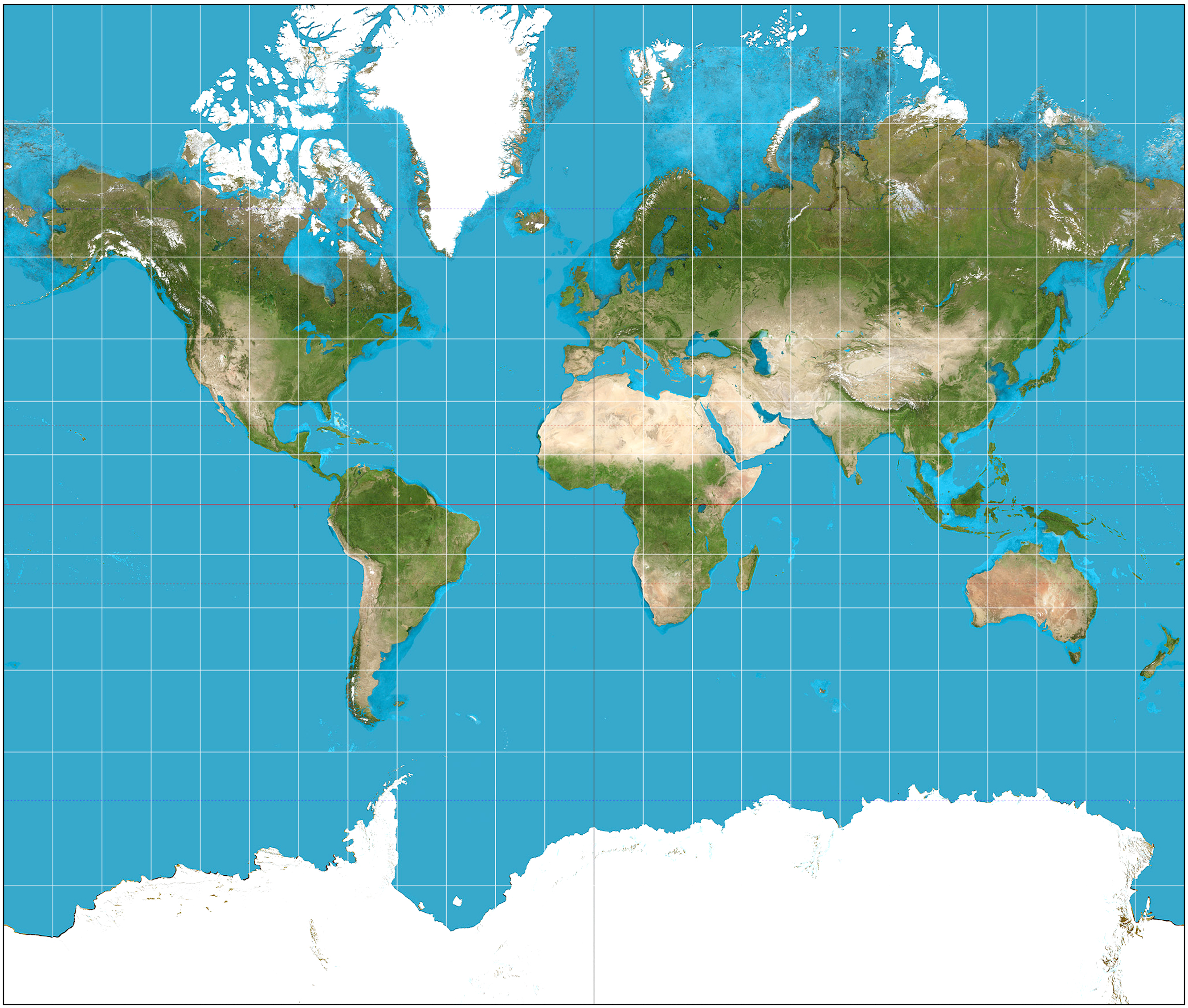

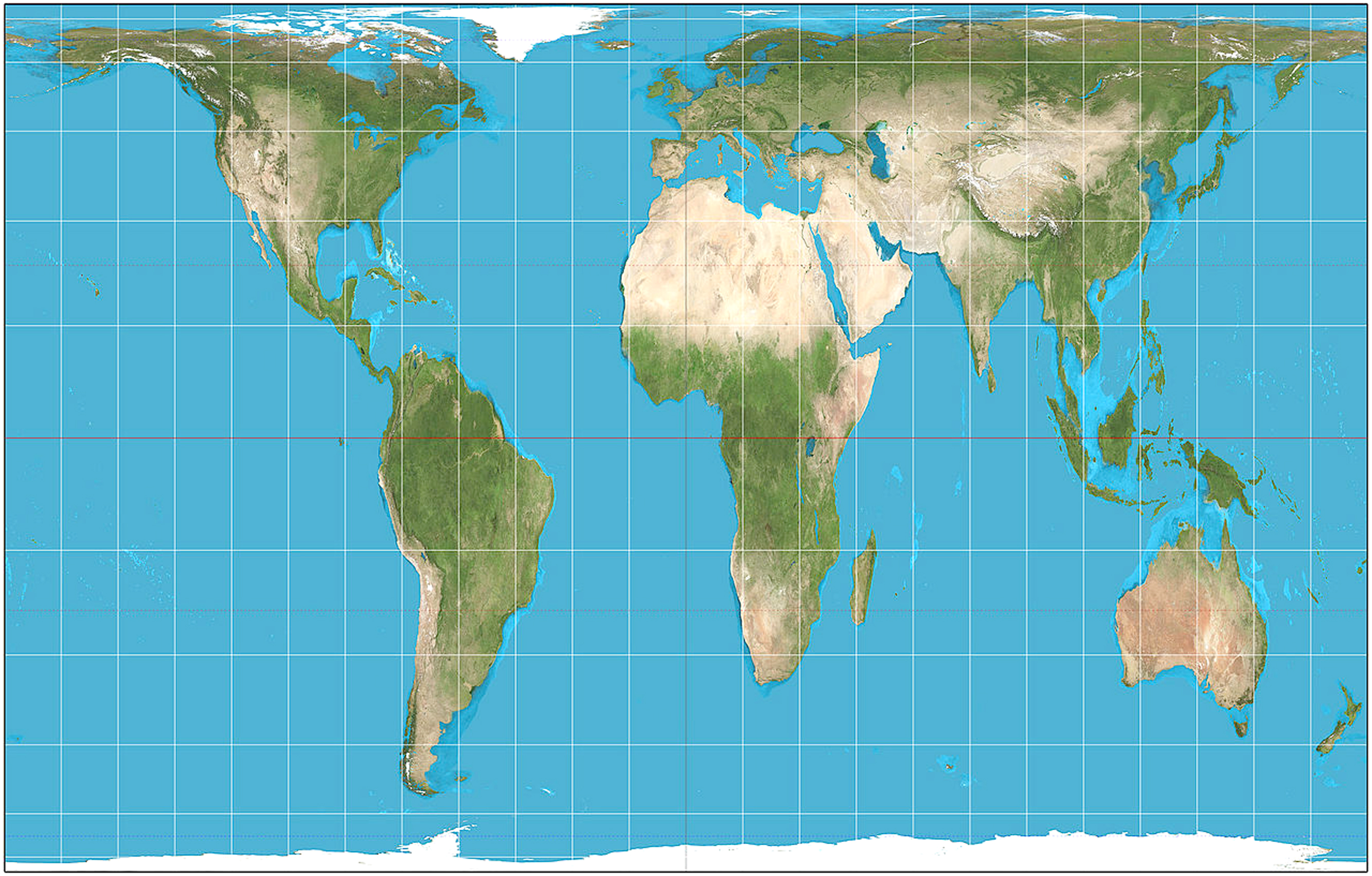

When I was growing up — in the Antediluvian Age when everyone smoked Lucky Strikes and cars all had clutches and carburetors — the maps in my grade school rooms had 48 states on them.

When I was growing up — in the Antediluvian Age when everyone smoked Lucky Strikes and cars all had clutches and carburetors — the maps in my grade school rooms had 48 states on them.

Those classroom roll-down maps were beautiful to my young eyes — all that green, yellow and ruddy brown in wood engraving density. They are maps that have never been equalled, and I knew, looking at the map, pulled down in front of the black chalkboard, that I wanted to go to every one of those states and see if Colorado were really the color of chestnuts, if Florida were really Kelly green. It seemed so lush.

Over the years, I’ve gone to — and written about — all 48 contiguous United States, seven Canadian provinces, a couple of edgings into Mexico and a few places in Europe and Africa.

In each of the places I’ve been, there is a top sight to see, like the Grand Canyon in Arizona or Yellowstone in Wyoming. And I’ve loved them all.

But there are also smaller, less well-known places that have quietly become some of my favorites. I’m sure everyone has the same: places where something special happened, or that sum up the qualities of a state or region, or that just seem so relaxed and beautiful that they draw you back over and over.

For me, such places are often remote from normal tourism attractions. I am a sucker for unspoiled grasslands in the Great Plains, for alligator-filled swampland in the South, for backcountry roads in the Appalachians. Others may look for happy crowds to join, for music and dancing or roller coasters. My favorites, however, tend to be empty of people, silent and to provide long views over a significant arc of the planet.

So, here are a few of those places, listed state by state.

Alabama

If you want to learn about the Deep South and how much it has changed, you should visit Selma. It is where the great Civil Rights march of 1965 began, crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge and heading on to the state capitol at Montgomery. If you think the battle is over, you should visit Selma and see, despite how far we have come, how distant is the horizon.

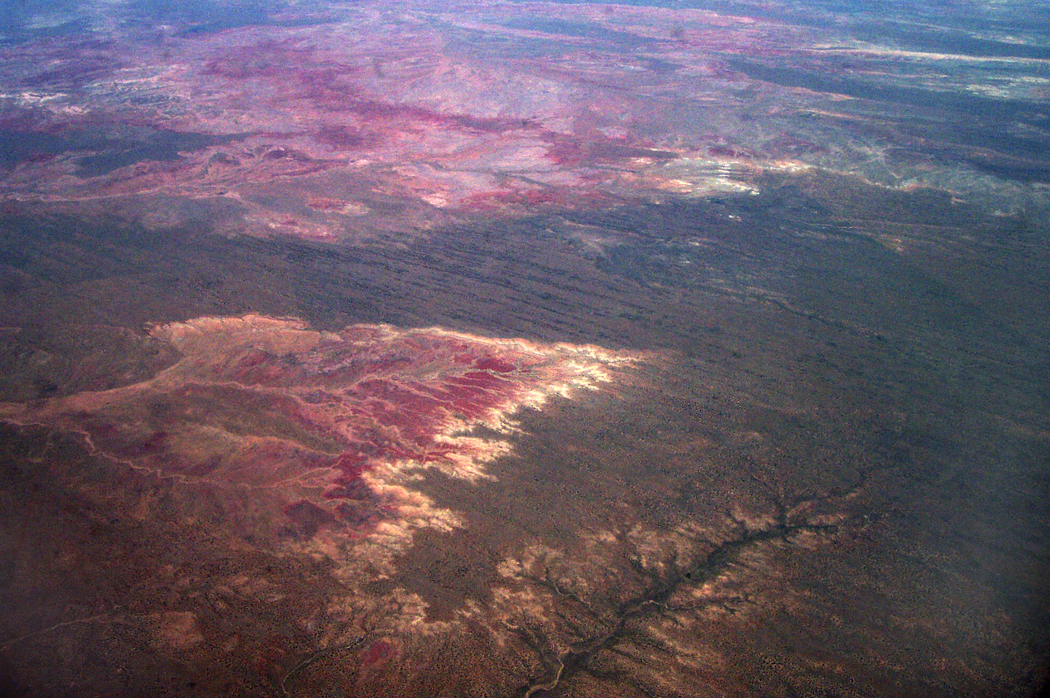

Arizona

Arizona

Of course, the Grand Canyon is on our license plates, but almost any other square foot of the state is nearly as wonderful, from Hoover Dam to Douglas, from Four Corners to Yuma. But I have a special place in my heart for an obscure exit ramp from I-17 north of Phoenix. Badger Springs Road is a bit of largely undisturbed desert, with trails and cactus, and I can always pull off the highway and find a bit of peace and quiet.

Arkansas

The state is rich in rural areas, craggy in the north, flat and muddy in the east through the Mississippi flood plain, steamy with hot springs toward the south. But the little town of Toad Suck in the center of the state seems even a little quieter, a little more remote than most, and is graced with a state park as well, along the Arkansas River. No hotels, but friendly people.

Northern California

California is too rich; I have to split it in two. Even then, I could name a dozen places in each half: In the north — Tule Lake National Wildlife Reserve, Mono Lake on the eastern side of the Sierras, Lassen National Park, the Humboldt Redwoods, the tule marshes along the Sacramento River. But I keep coming back to Owens Valley, just below Mt. Whitney. From the soda-flat Owens Lake north to the ruins of the Manzanar Relocation Center — where Japanese-Americans were interned during World War II — the valley is both picturesque — the Alabama Hills where so many Western films were shot among the wonderland of rocks — and historic — in addition to the concentration camp, there is the sorry and violent tale of how a thirsty Los Angeles stole the valley’s water earlier in the century.

Southern California

East of San Diego is one of California’s most pristine deserts. It is called Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and it is the primordial home of all those Washington palm trees that line the streets of Phoenix. Borrego Springs is a surprisingly kempt little town in the middle of it, but the rest of the park usually seems as empty as a college campus during spring break.

Colorado

For most people, the state probably brings to mind skiing or expansion baseball, or an over-hyped beer, and certainly Colorado is best remembered for post-card mountains — all those “fourteeners” — but I love the Pawnee National Grasslands, one of the best places to get a sense of what the West was really about, what the Great American Desert was — not desert, but the Great Plains, vast, sweeping and grassy.

Connecticut

There is no more peaceful a river valley in the nation than the Housatonic north of New Milford. The Appalachian Trail winds along a portion of its banks. There are covered bridges, meadows and not too far away, near Cornwall, there is a large stand of virgin white pine, called the Cathedral Pines. U.S. 7 parallels the river most of the way.

Delaware

Delaware is a tiny state, and most people notice it, if at all, for the chemical plants and refineries that stick their bellowing smokestacks into the air, and the highways that pass through it on their way elsewhere, up over the twin Delaware Memorial Bridge. But there are the “Hooks” — Prime Hook and Bombay Hook national wildlife refuges, swampy and woodsy on the broad mouth of Delaware Bay.

Florida

If you cannot get enough of the Everglades, or if the national park is too crowded, head north off U.S. 41 on any of a dozen gravel roads into Big Cypress National Preserve. Or take the loop road to the south, through incredible cypress wetlands, with sagging Spanish moss and blackwater swamps.

Georgia

The Okefenokee is my favorite swamp. That’s saying a lot. I’ve seen more wildlife in it than in any other. Drive up Georgia 177 from Edith into the Stephen C. Foster State Park and rent a canoe. Paddle within inches of swimming alligators. Look into the trees for the snake birds — anhingas — with their darting necks and their wings spread out in the sun to dry.

Idaho

With its camas prairies, steep mountains and gaping canyons, the Nez Perce Indian Reservation is one of the most beautiful parts of this beautiful state. You can see the valley where Chief Joseph began his tragic 1,500-mile unsuccessful flight to freedom for his people in 1877.

Illinois

Chicago has big shoulders in the north, but down at the very bottom are the forlorn toes of Cairo, one of the most memorable of Mississippi River towns. It is aging, with peeling paint and boarded up storefronts, but you can feel in the humid air the history behind it. And you can see the conjoining of the muddy Mississippi water with the clearer, faster moving Ohio River. Boats and barges move past in the misty mornings like iron dreams.

Indiana

If you want to find the prototype of Disney’s “Main Street U.S.A.,” you couldn’t do better than to see Paoli, in the southern part of the state. No more perfect quiet little Middle-American village can be found. There are no tourists and nothing to do, but imagine what it must be like to live there, under the spreading chestnut trees just off the town square.

Iowa

Iowa is sometimes surreal: At the bottom of the bluffs of the Mississippi are cities filled with Victorian architecture. There are trees and vines. On top of the bluffs, there are endless rolling farms, with silos instead of trees, like some Grant Wood painting. The best of the cities is Dubuque, one of the greatest surprises of my travels. It is one of America’s most beautiful cities.

Kansas

If you want to get away from civilization, you can hardly do better than the middle of Kansas. Just north of Lebanon is the “Geographical Center of the Conterminous U.S.,” which is a highly qualified title to be proud of. But you stand there, looking out over the grass and wonder, if they dropped the Big One here, would anyone hear it?

Kentucky

The state is mud in the west, limestone in the center and coal in the east. Among the stumpy, round-bumped mountains of coal-mining Harlan County and neighboring Letcher County, are some of the poorest homes and interesting people of the country.

Louisiana

It surprises even me, but one of my favorite places is along the Interstate. For 20 miles, I-10 rises on piers over the Atchafalaya Swamp. Take an exit into the dark woods and drive along the river into old, mossy river towns, built where the terra is not so firma. Even the pavement seems squishy beneath your feet.

Maine

Everybody heads to Bar Harbor, where the T-shirt shops and frozen yogurt stores are chock-a-block. Pass on that and head to Schoodic Point further north. Also part of Acadia National Park, it is one of the ruggedest, rockiest parts of the rocky Maine coast.

Maryland

Antietam National Battlefield, near Sharpsburg, is the most emotional Civil War site I have visited. Every aspect of the fight, and all the blood and bullet-holes, seem spread out graphically, and the spirits of the dead and suffering seem almost palpable at the sunken road called Bloody Lane.

Massachusetts

Arrowhead is the one-time home of Herman Melville in Pittsfield. The house is actually a character in many of his stories, and you can look out the second-floor window of his study, where he wrote Moby Dick, and see the saddle-back peak of Mt. Greylock to the north, “Charlemagne among his peers.”

Michigan

The Upper Peninsula is a big place, but everywhere you turn, there are forests, lakes and rivers, including Papa Hemingway’s Big Two-Hearted River. It’s hard to pick a single place, but there is always the drive on U.S. 2 along the southern shore of the peninsula along Lake Michigan.

Minnesota

A river doesn’t really start from a single source, but the agreed fiction is that the Mississippi begins at Lake Itasca, southwest of Bemidji. The lake is not that large, by Minnesota standards, and seems quite placid. The “father of waters” begins at a reedy little outlet that you can step across and brag you crossed the Mississippi on foot.

Mississippi

The blues began in the Mississippi Delta, and they are still played in the shabby juke joints of Clarksdale, one of those old, cracked-concrete, grass-in-the-railroad-ties, dying-downtown Deep South county seats. Everybody you see, sitting on their porch fronts, seems more human, more profound. Maybe it’s the blues.

Missouri

The Ozark Mountains can be beautiful, with lichen-covered limestone and rivers that disappear underground. Like at Big Spring State Park on the Current River, where the river comes gushing back out of the rock like a fountain.

Montana

Chief Joseph began his three-and-a-half month trek in 1877 in Idaho, he ended it on the flat, grassy, empty plains of northern Montana, at a place called the Chief Joseph Battlefield near the Bears Paw Mountains, only 40 miles from the safety his Nez Perce Indians sought in Canada. He was captured by the U.S. Army, and promised “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

Nebraska

People look at me funny when I tell them that Nebraska is probably my favorite state to visit. The sand hills, the puny “national forest,” the Platte River and Scotts Bluff — they all seem unbearably windblown and lonesome. I love them all, but in North Platte, you cannot feel alone at the biggest railroad freight yard in the country. You can watch trains all day.

Nevada

If Nebraska is my favorite state, Nevada is probably my least favorite. It is empty, true, but its emptiness seems hard and thoughtless, like a biker at a roadside bar and casino. But I cannot deny the beauty of such places as Big Smoke Valley, between the Toiyabe and Toquima mountains, and the wide sagebrush plains where you don’t see a car for hours, but maybe a dozen dusty pickups.

New Hampshire

The Kancamagus Highway is one of the most beautiful drives in the country, winding through the White Mountains along the Swift River. It goes from Lincoln to Passaconaway and passes some stunning stony waterfalls.

New Jersey

This is the state where I grew up. I came to despise the suburban banality of most of the state, but I loved two things: the northwest corner, with its minuscule mountains and bucolic forests; and most of all, the industrial corridor of the Jersey Turnpike, with its refineries, chemical plants and the always-beautiful Pulaski Skyway.

New Mexico

At the top of the Sacramento Mountains, in the Lincoln National Forest is a place called Cloudcroft. There is great camping, wild animals and — usually — clean air that is so clear, it could cut diamonds.

New York

New York offers more than any other single state except California. There are dozens of favorite sites, from Montauk Point to Niagara Falls. But I will always have a special affection for Harriman State Park, along the Hudson River, and Bear Mountain, that looks down at the gorge, just south of West Point and its military academy. Seven Lakes Drive, through the park, is what nature in the East is all about.

North Carolina

No question here: Ashe County, tucked up in the northwest part of the state, above the Blue Ridge, is away from the normal tourist loop, but more beautiful than any other place north of the Smoky Mountains. Any gravelly back road will take you to something surprising and there is the New River to canoe down.

North Dakota

It hardly counts for anything, and there is no real reason to visit, but I cannot get enough of Zap, a tiny crossroads, where the roads don’t go anywhere. Between Beulah and Golden Valley, Zap sits among the rising and dropping swell of the grasslands, with the occasional pond for cattle to drink from.

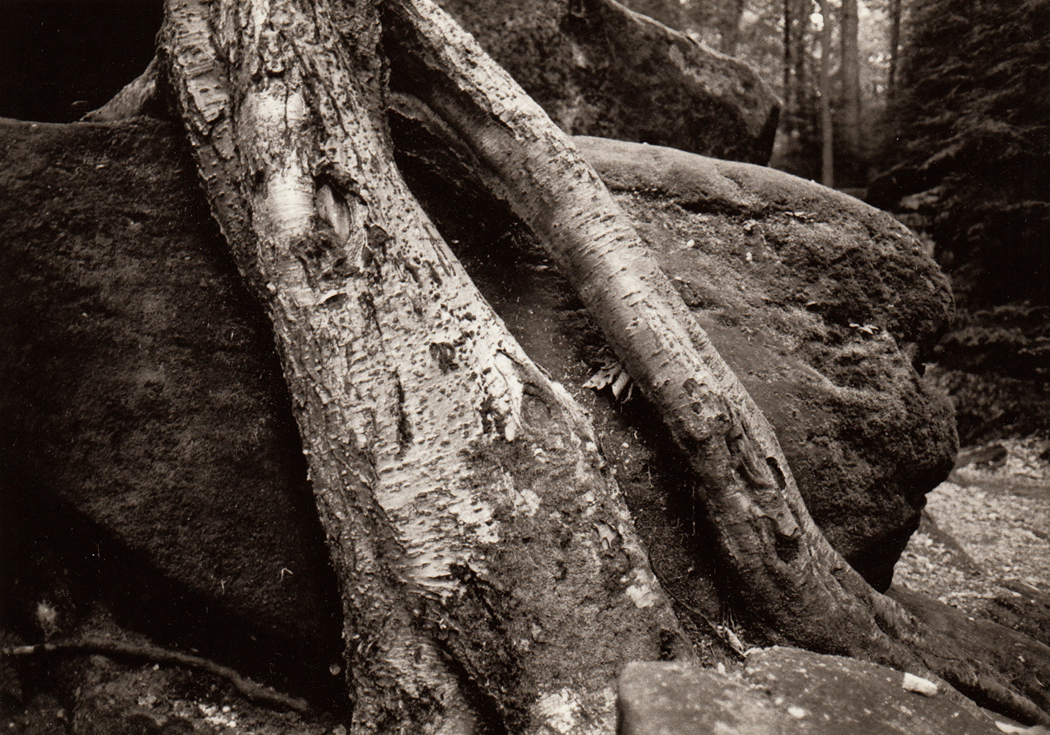

Ohio

Just south of Cleveland, there is a small bit of woods and rock called Virginia Kendall Park. It is right next to the larger Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, and benefits from more people going there than here. There is a rocky bluff in the middle of the park and echoing voices in the forest among the leaf litter.

Oklahoma

One of the worst massacres of the so-called Indian Wars took place just outside of Cheyenne, along the Washita River. The site is now nothing but grass, a line of trees along the water, and some outcroppings of rock. But the surrounding Black Kettle National Grasslands can give you a real sense of what the land looked like 121 years ago.

Oregon

The Columbia River Gorge is one of the scenic wonders of America, and one of the most scenic drives is along the old, outmoded Columbia River Gorge Scenic Highway, which rises up the mountainside above the interstate highway, and takes you through more waterfalls than any comparable stretch of road outside Hawaii.

Pennsylvania

The second most famous house in America — after the White House — is probably Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, a vacation home he designed for Pittsburgh’s wealthy Kaufman family beginning in 1934. It is also one of the most beautiful buildings in the country, sitting literally atop a waterfall and jutting out over the small forest glen.

Rhode Island

If you’re on the A-list, you’ll naturally gravitate to Newport and its extravagant mansions. I’m not on that list; I prefer the more humble Conanicut Island, where real people live. It sits in the middle of Narragansett Bay and gives you a good sense of what life on the bay is like.

South Carolina

Myrtle Beach gets all the traffic and spring-breakers, but Huntington Beach, 10 miles further south along Murrell’s Inlet, is the better place to be. With Huntington Gardens just across the street, with all those animal sculptures of Anna Hyatt Huntington, and a fresh-water alligator pond next to the salt marsh, Huntington Beach is a great — a great — place for seeing birds.

South Dakota

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation may be poor, but it is beautiful. And as with many places noted for its poverty, it is very real. The people take the time to talk to you and there is history at every turn in the road — not all of it very comfortable for an Anglo to remember.

Tennessee

Most of the crowds at Great Smoky Mountains National Park gather along U.S. 441 across the crest of the range, or in Cades Cove in the southwest of the park. But one of the great drives, and less crowded, is up the Little River Road through the back side of the park. It follows the cascading Little River most of the way, and finds its way back to the visitors center at Sugarlands.

Texas

Even Texans will tell you the center of their state is the best part: The Texas Hill Country is an oasis in the middle of a state that sometimes seems like nothing more than the world’s largest vacant lot. And the best part of the Hill Country is found at the LBJ Ranch near Johnson City. It is no wonder that our 36th president loved his ranch so much. It is a jewel in a perfect setting.

Utah

Is there a square inch of the state that doesn’t deserve to be a national park? I haven’t found it. But one of the most overlooked gems is the ride along Utah 128 from Moab to Cisco. Through most of its route, the road seems to be the one you would imagine at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Well, perhaps that exaggerates it a wee bit. But it is special.

Vermont

Near Plymouth is the birthplace and homestead of Calvin Coolidge, who has recently lost his title as the president we made the most jokes about. In fact, Silent Cal was a smart cookie and not at all the buffoon stand-up comics make him out to be. He was raised in a tiny Yankee village that is preserved as a state park.

Virginia

Virginia is another state that seems to have more than its fair share of special places. Perhaps it’s history, perhaps geography, but almost anywhere you turn, there is something that will draw you back over and over. Still, there is something special about Thomas Jefferson’s mountaintop home, Monticello, a monument to just how profoundly beautiful a little nuttiness can be. The Age of Reason meets Henry Thoreau.

Washington

Eastern Washington is largely a blank spot in America’s consciousness. Seattle, the Olympics, the Cascades, Mt. Rainier — they are all in the west. But there is hardly an odder or more peculiar and spooky landscape on Earth than what is called the Channeled Scablands east of the Cascades. The Grand Coulee Dam blocks the Columbia River there, where a prehistoric flood scraped the earth clean for hundreds of miles.

West Virginia

The Hawks Nest, on U.S. 60 between Gauley Bridge and Ansted, looks out over the deep declivity of the New River Gorge and is one of the great scenic views of the eastern U.S.

Wisconsin

Southern Wisconsin has many treasures, including the Mustard Museum in Mt. Horeb, and the world’s largest six-pack of beer at La Crosse, but nothing can beat the genuine zaniness of the Dickeyville Grotto, a religious site in Dickeyville created out of broken bottles, seashells, stones and broken crockery. It is one of the great “outsider art” sites, and don’t miss the tribute to Columbus.

Wyoming

What’s the highest, most alpine road in America that actually goes somewhere? Undoubtedly, it is the Bear Tooth Highway, U.S. 212 from Red Lodge, Mont., to Yellowstone National Park. It climbs up over Bear Tooth Pass at 10,940 feet and provides more long Rocky Mountain views than any other road. Look out for the marmots.