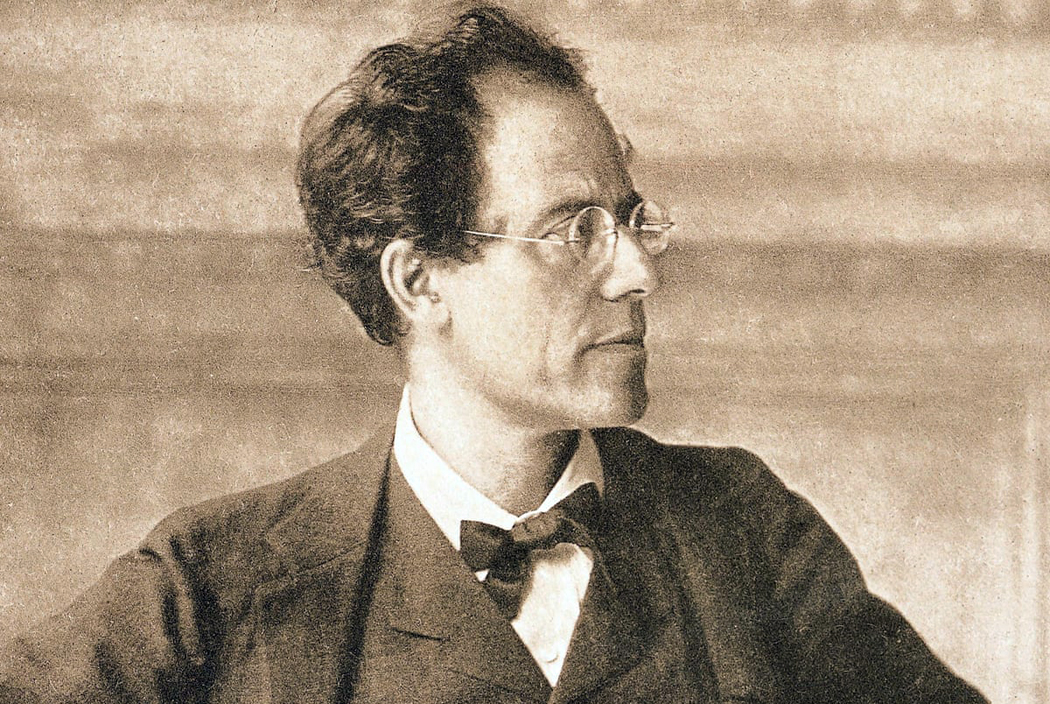

There is Mahler before Bernstein, and Mahler after him. This is not to say that Lenny is the summum bonum of these nine-plus symphonies, but that before his 1960’s advocacy, Mahler was one of those niche composers that a few people knew about and appreciated, and afterwards, no right-thinking conductor could fail to offer a complete cycle — Mahler joined Beethoven, Brahms and Tchaikovsky and one of those whose works would be recorded by the yard. A Mahler program now draws a paying audience like almost no other.

But there is Mahler and there is Mahler. When everyone gets into the act, the quality level evens out — It’s hard to find a really bad recording anymore, and it is also hard to stand out with something exceptional. Yet, both ends do still exist.

I have not heard every release; no one could, not even David Hurwitz, who is as close to nuts as anyone I know of. But I have experienced a whole raft of Mahler recordings and I have my favorites, and a few excrescences that I have to keep as “party records” to share with commiserating friends.

My bona fides include more than a half-century of listening to classical music, reading scores, and being a retired classical music critic on a major daily newspaper. I have owned at least 15 complete Mahler cycles and uncounted individual CDs and LPs — going back to the 1960s. I did disgorge about two-thirds of my collection of CDs when I retired eight years ago, but even since, I have added more Mahler (among others) and currently sit with 10 full sets and two shelves of individual recordings. Am I as nuts as Hurwitz? I leave that to the jury. (It isn’t only Mahler: I once owned 25 complete sets of Beethoven piano sonatas and 45 recordings of the Beethoven Violin Concerto).

Yes, I listen to a boatload of music. I cannot imagine my life without music.

And I have my Top 10 list of Mahler recordings. Really, a Top 11 — one for each of the nine completed symphonies, and add-ons for the incomplete 10th, for Das Lied von der Erde, and the song cycles, so it’s really like a Top 15 or so. And there are a few bombs I want to include, just for fun. Let’s take them in order.

Symphony No. 1 in D

The symphony begins with an ethereal A, barely audible and transforms into a cuckoo call, evincing nature, the woods and eternity, but then opens up into the fields and streams borrowed from Ging heut’ Morgen über’s Feld in his song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen. The first four Mahler symphonies all borrow from his songs. The third movement is a grotesquerie built from a minor-key version of Frere Jacques played first by a solo double bass; it is an ironic funeral march, interrupted by klezmer music and a bit of gypsy wedding. It is one of the most peculiar movement from anyone’s symphonies.

Then it all burst out in a tormented and blazing fourth movement with horns wailing out over all, and comes to an abrupt conclusion with an orchestral hiccup.

Then it all burst out in a tormented and blazing fourth movement with horns wailing out over all, and comes to an abrupt conclusion with an orchestral hiccup.

The symphony is qualitatively different from the ones that follow, but it is easier for most first-time listeners to comprehend. It is a great place to start a Mahler journey.

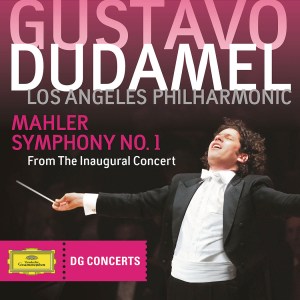

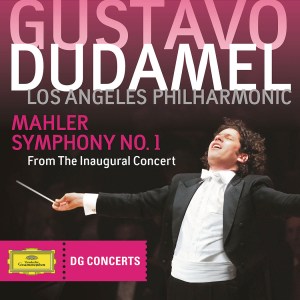

The greatest version I ever heard live was Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic; it blew me away. There is a live recording, from the young maestro’s debut concert in LA. It is hard to get the same effect from a recording, but this is my sentimental favorite. But there are some other great ones.

The consensus (but not universal) favorite is Raphael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1968. It includes the Lieder eines fahrended Gesellen and Dietrich Fischer-Deiskau.

The consensus (but not universal) favorite is Raphael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1968. It includes the Lieder eines fahrended Gesellen and Dietrich Fischer-Deiskau.

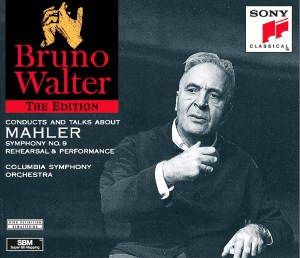

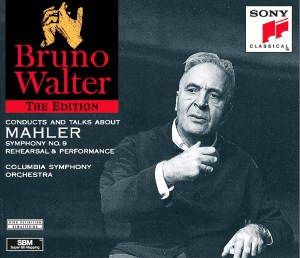

The version I first learned from, a billion years ago in another galaxy, and on vinyl, was Bruno Walter’s with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. Walter knew Mahler and premiered his Ninth Symphony. The sonics are not always great, but there is tremendous authority in Walter’s Mahler.

Symphony No. 2 in C-minor (“Resurrection”)

Many people hold the “Resurrection Symphony” as their nearest and dearest, with its uplifting finale of rebirth and optimism. But I have always found the end a touch forced and insincere, as if Mahler really, really wanted to believe in a renewed life after death, but couldn’t, and could only mouth the words. “Words without thoughts never to heaven go.”

Yet, its music is still magnificent, especially the first movement funeral march, which comes to a climax so disturbing and dissonant, he never matched it until the orphan adagio of his 10th symphony. The inner movements are some of the most beautiful he ever wrote and the alto solo, Urlicht, is transcendental.

Yet, its music is still magnificent, especially the first movement funeral march, which comes to a climax so disturbing and dissonant, he never matched it until the orphan adagio of his 10th symphony. The inner movements are some of the most beautiful he ever wrote and the alto solo, Urlicht, is transcendental.

Everyone, it seems, has taken a crack at the “Resurrection”, including businessman Gilbert Kaplan, who learned to conduct only to lead this symphony and never conducted anything else. (OK, he did make a stab at the Adagietto from the Mahler Fifth, but that hardly counts.)

My favorite is Otto Klemperer with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus. Klemperer always makes the music feel as important as it needs to be; he seems to believe in what it says, not merely to play the notes.

Symphony No. 3 in D-minor

There are some music you cannot listen to very often. Beethoven’s Ninth, for instance, or the Bach Matthew Passion. They are too big, too meaningful, too overwhelming, that to maintain the sense of occasion, you can only pull them out at special moments. You have to be ready to accept what they have to offer. It is almost a religious experience.

The Mahler Third last an hour and a half. It is almost an opera without words, except there are singers. It is a full evening by itself. But if you are not in the right frame of mind, it can just seem endless. The first movement alone lasts longer than any Haydn symphony.

Mahler explained his ideas for the symphony, though he later recanted. The words are not what the symphony says, but they give an approximation. The first movement is “Pan awakes; summer marches in,” and pits a relentless and ruthless nature, “red in tooth and claw,” against the riotous optimism of the season of growth, in an overwhelming march of joy and hedonism.

The second movement is “What the flowers of the meadow tell me.” The third is “What the animals of the forest tell me.” In the fourth, an alto sings “What man tells me,” in a doleful lament that “Die Welt ist tief,” “The world is deep.” Following that comes “What the angels tell me,” with a choir and bells telling of “himmlische Freude” — heavenly joy.

But all of this, for an hour, is really prolog to the final movement Adagio, “What love tells me.” It is built on a theme taken from Beethoven’s final quartet and its “Muss es sein? Es muss sein.” (“Must it be; it must be”). It is a 22-minute-long meditation, rising to ecstasy.

When the premiere was given in 1902, Swiss critic William Ritter wrote this finale was “Perhaps the greatest adagio written since Beethoven.” If you can come away without collapsing into a puddle of weeping, you’re a better person than I am.

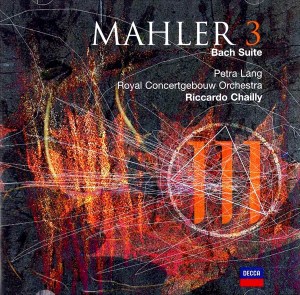

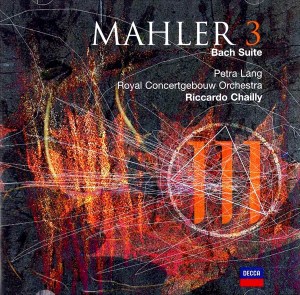

The recording that overwhelms me more than any other, not only because of the performance, but because of its engineering and immediacy of sound quality is Riccardo Chailly and the Royal Concertgebouw.

A nearly equal second, in slightly less perfect sound, is Leonard Bernstein’s 1961 recording with the New York Philharmonic. It is the gold standard for the finale.

Symphony No. 4 in G

On the opposite end of the emotional scale — and what a relief — comes the Fourth Symphony, with its sleigh bells and Kinderhimmel. It is, without doubt, Mahler’s happiest symphony. It is also his shortest. Coincidence?

On the opposite end of the emotional scale — and what a relief — comes the Fourth Symphony, with its sleigh bells and Kinderhimmel. It is, without doubt, Mahler’s happiest symphony. It is also his shortest. Coincidence?

But I’ve got a problem picking a best, because there are three performances I cannot do without, each highlighting a different aspect of the work.

First, there is Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra, recorded in November, 1939. Mengelberg knew Mahler, and we have evidence that Mahler endorsed Mengelberg’s interpretation of the symphony, although that endorsement came for earlier performances. Mahler died in 1912 and this recording is from 27 years later. Still, it is the best evidence we have for the way Mahler probably intended his work to sound. And, compared to the way it is played nowadays, it is ripe with violent tempo changes and swooping portamentos.

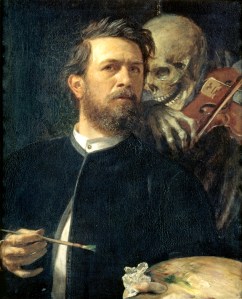

Second, there is Benjamin Zander, with the Philharmonia. In the hour-long discussion disc packaged with the performance, Zander makes the case that Mahler wanted the violin soloist in the second movement to play like a country fiddler, not a trained violinist. A “Geige,” not a “Violine.” He has the violinist retune his fiddle a full tone sharp to play the Totentanz — he is to be Freund Hein, or “Friend Hank,” a nickname for the Grim Reaper. Zander is the only conductor to really take the composer at his word; most recordings, the soloist can’t bring himself to make the ugly sounds Mahler wanted, and smooths the part’s rough edges. It should sound like the Devil’s fiddle in Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat, with that edge.

Second, there is Benjamin Zander, with the Philharmonia. In the hour-long discussion disc packaged with the performance, Zander makes the case that Mahler wanted the violin soloist in the second movement to play like a country fiddler, not a trained violinist. A “Geige,” not a “Violine.” He has the violinist retune his fiddle a full tone sharp to play the Totentanz — he is to be Freund Hein, or “Friend Hank,” a nickname for the Grim Reaper. Zander is the only conductor to really take the composer at his word; most recordings, the soloist can’t bring himself to make the ugly sounds Mahler wanted, and smooths the part’s rough edges. It should sound like the Devil’s fiddle in Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat, with that edge.

In all his Mahler recordings, Zander is scrupulous in following the anal retentive storm of written instructions Mahler included in his scores. If this means the long-haul structure of the work is sometimes disrupted for the spotlit detail, well, that’s the nature of Romanticism over Classicism. Those details were put there for a reason; we should hear them.

In all his Mahler recordings, Zander is scrupulous in following the anal retentive storm of written instructions Mahler included in his scores. If this means the long-haul structure of the work is sometimes disrupted for the spotlit detail, well, that’s the nature of Romanticism over Classicism. Those details were put there for a reason; we should hear them.

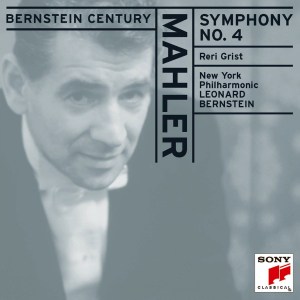

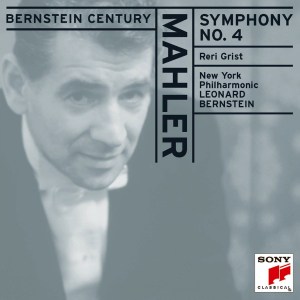

The third recording is Bernstein’s first version, with the New York Philharmonic and soprano Reri Grist. Bernstein’s Mahler is always good, but sometimes, it is the best, and this is one of those times. Grist has a fresh voice that is perfect for the innocent text of the finale, which is a child’s vision of what heaven will be like (“Good apples, good pears, good grapes … St. Martha must be the cook.”)

Symphony No. 5

Wagner has his “bleeding chunks,” and Mahler has his Adagietto. Everyone knows the Adagietto, from movies and TV commercials. But the whole symphony, the first one since the First Symphony not to have voices, is a great rumbustious tussle, from its funeral march start to its manic contrapuntal finale, where he takes five melodic fragments, stated at the outset, and combines and recombines them like a Braumeister.

Wagner has his “bleeding chunks,” and Mahler has his Adagietto. Everyone knows the Adagietto, from movies and TV commercials. But the whole symphony, the first one since the First Symphony not to have voices, is a great rumbustious tussle, from its funeral march start to its manic contrapuntal finale, where he takes five melodic fragments, stated at the outset, and combines and recombines them like a Braumeister.

The Adagietto fourth movement was, per Mahler, intended as a love letter to his wife, Alma, but is so elegiac that it has become the aural metaphor for loss and grief. Considering Alma’s serial infidelities, perhaps it is only fitting that the movement has morphed in its cultural meaning. (One critic calls Mahler “a composer with a dodgy heart who married a trollop.” “Alma, tell us: All modern women are jealous. You should have a statue in bronze, for bagging Gustav and Walter and Franz.”)

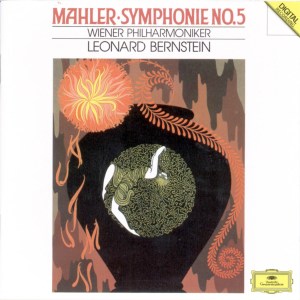

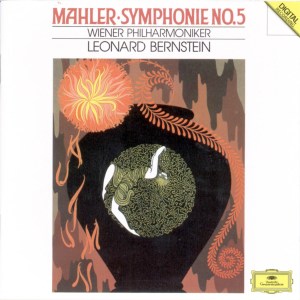

The recording to have is Bernstein’s second recording, with the Vienna Philharmonic. It has beautiful playing from one of the world’s best orchestras, and all the energy and commitment that emanates from Lenny’s spiritual leadership.

The recording to have is Bernstein’s second recording, with the Vienna Philharmonic. It has beautiful playing from one of the world’s best orchestras, and all the energy and commitment that emanates from Lenny’s spiritual leadership.

Another legendary performance is John Barbirolli’s with the New Philharmonia. If you think Bernstein’s fever is suspect, then reach for a cold bottle of Sir John.

Symphony No. 6 (“Tragic”)

Labeling any of Mahler’s symphonies as “Tragic” may seem redundant, but this is clearly his gloomiest, opening with a relentless stomp, stomp, stomp of a marche fatale and leading to the crushing hammer blows of destiny in the finale.

Nevertheless, it has what I think is an even more persuasive love letter to Alma in the slow movement, which has to be one of the most tender and lovely in all of the canon.

But Mahler never quite figured out if it should be the second or third movement, so nowadays, you find it both ways in performance, and find angry and assertive essays by critics proving once and for all it simply has to be the way they see it. Me, I like the adagio second to separate the angry first movement from the angry scherzo, which shares its rhythm with the first. Play them back to back before the adagio and it can seem like too much of the same thing. But then, that’s my opinion; you are free to have yours.

Then, in the finale, Mahler never quite resolved whether there should be three hammer blows or only two. He was a seriously superstitious man and feared that a third hammer blow might prefigure his own death, and took it out of the score. But hammer blows come in threes in life — at least in Mahler’s — and I prefer all three to be there. Nor did he ever quite specify what he meant by hammer blows; they are written into the score, but how should they be produced? Each orchestra is left to come up with its own solution. Some have used hammer and anvil, others have built large resonant wooden boxes hit with great wooden mallets. There’s a lot of room for interpretation.

Then, in the finale, Mahler never quite resolved whether there should be three hammer blows or only two. He was a seriously superstitious man and feared that a third hammer blow might prefigure his own death, and took it out of the score. But hammer blows come in threes in life — at least in Mahler’s — and I prefer all three to be there. Nor did he ever quite specify what he meant by hammer blows; they are written into the score, but how should they be produced? Each orchestra is left to come up with its own solution. Some have used hammer and anvil, others have built large resonant wooden boxes hit with great wooden mallets. There’s a lot of room for interpretation.

Ben Zander comes to the rescue: His recording includes both the duple and triple hammer blows. You get to choose which finale you want to hear. As usual, Zander is perfect for following Mahler’s precise instructions in the score: a sforzando here, a ritardando there, a subito piano or a purposeful mix-mash of rhythms there. Now make the clarinet sound like a dying cat, now let the violins swoop with a portamento. Zander obeys where most other conductors smooth it all out to make pretty. This should not be a pretty symphony.

Symphony No. 7

Guess what? Whether two or three hammer blows, Mahler didn’t die after the Sixth Symphony, which may explain why the Seventh is so giddy. All the other symphonies are programmatic in some way, with funeral marches, or heroic deaths, but the Seventh is just music. Mahlerian music, which means fantastic orchestrations and effects. But no overt meaning.

It has five movements. The inner three are a scherzo sandwiched between two nostalgic sweetnesses he called “Nachtmusik,” or “night music.” In them, he uses rustic cowbells to symbolize — cowbells — and adds a mandolin and guitar. They couldn’t be lovelier. Between them is a vicious scherzo.

But then, there’s the finale, which really makes no sense at all. It’s a complete hodge-podge, starting with a manic tympani solo and rushing off like a Turkish Pasha into what sounds like Ottoman grandiosity. But you have to remember the advice of the Talking Heads: “Stop Making Sense.” Just enjoy the effervescent joy of it all, up to the penultimate C-augmented horn chord before the final tonic C. One of the oddest endings before Sibelius’s Fifth.

The Third and the Ninth are certainly deeper and more profoundly moving, but the Seventh is my favorite for when I just want to hear Mahler without having to weep and sob and contemplate the Weltschmerz of it all.

My go-to recording is a sleeper. Daniel Barenboim is not known as a great Mahler conductor, but his recent Mahler Seventh, with Staatskapelle Berlin on Warner Classics is brilliant and one of the best engineered recordings I’ve heard, so you get not only a perfect performance, but a recording that sounds more like an orchestra playing live in your room than any other. He hits the crazed finale with the perfect get-on-the-roller-coaster attitude.

My go-to recording is a sleeper. Daniel Barenboim is not known as a great Mahler conductor, but his recent Mahler Seventh, with Staatskapelle Berlin on Warner Classics is brilliant and one of the best engineered recordings I’ve heard, so you get not only a perfect performance, but a recording that sounds more like an orchestra playing live in your room than any other. He hits the crazed finale with the perfect get-on-the-roller-coaster attitude.

I’ve been choosing great performances to recommend, but really bad ones can be fun, too. There is a Mahler Seven that is so unbelievably bad, you just have to hear it. Otto Klemperer is — let’s be honest — a really great Mahler conductor. Many of his recordings rank at the top of the list. But his Seventh is a real dog. What was he thinking? Barenboim comes in at 74 minutes. Klemp’s Seventh goes on for an hour and 40 minutes. Cheez Louise. It’s like Glenn Gould’s Appassionata, playing it like they were sight-reading it for the first time.

Symphony No. 8 (“Symphony of a Thousand”)

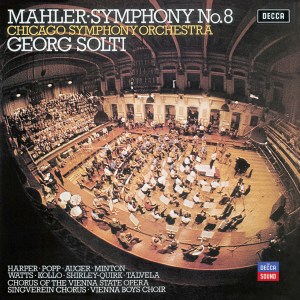

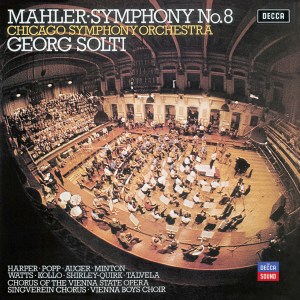

I’m afraid I have never warmed up to the Eight Symphony. Its first movement is outright hysterical — I don’t mean it’s funny, but rather the manic half of a bipolar cycle; and its second movement is an opera manque built on Goethe’s Faust that just seems to wander without getting anywhere. Maybe I just need to listen to it another 20 times or so to get it into my head. It was Mahler’s biggest popular success during his life, but it has not worn well with me.

I’m afraid I have never warmed up to the Eight Symphony. Its first movement is outright hysterical — I don’t mean it’s funny, but rather the manic half of a bipolar cycle; and its second movement is an opera manque built on Goethe’s Faust that just seems to wander without getting anywhere. Maybe I just need to listen to it another 20 times or so to get it into my head. It was Mahler’s biggest popular success during his life, but it has not worn well with me.

It is a choral symphony with an alleged 1000 performers taking part, including eight solo voices, two different choruses and an organ, which blares at the beginning when it all explodes open in a “Veni creator spiritus” — “Come, Creator Spirit” — like one of those tweets typed in all caps.

It has its fans. I am happy for them. George Solti and the Chicago Symphony is a consensus recommendation and zips through it all in under 80 minutes, which is shorter than almost all other performances, and therefore qualifies it as the greatest.

Symphony No. 9

Mahler had a congenital heart defect and he put its irregular rhythm into the beginning of his Ninth Symphony, an off-kilter beat that is the first thing we hear as the orchestra begins. Over that we hear the harp and muted trumpet. Added to that comes a little shiver in the strings followed by a two-note descending theme. These layers form the basis of the entire symphony, the way dot-dot-dot-dash forms the genesis of Beethoven’s Fifth.

Mahler had a congenital heart defect and he put its irregular rhythm into the beginning of his Ninth Symphony, an off-kilter beat that is the first thing we hear as the orchestra begins. Over that we hear the harp and muted trumpet. Added to that comes a little shiver in the strings followed by a two-note descending theme. These layers form the basis of the entire symphony, the way dot-dot-dot-dash forms the genesis of Beethoven’s Fifth.

There follows an earthy Ländler as a second movement and a scurrilous Rondo Burlesque for the third. The final adagio is a kind of culmination of Mahler’s death music. Instead of a funeral march or a heroic death, the music dwindles to a quiet and inevitable cessation of its heartbeat. It trails off in a morendo so still and hushed that in a good performance, you can never quite tell when the orchestra stops playing. It just dies away. The effect can be overwhelming. In some famous performances, the audience refrains from applauding for as long as five whole minutes before exhaling in bravos and cheers. It is music that strikes deep.

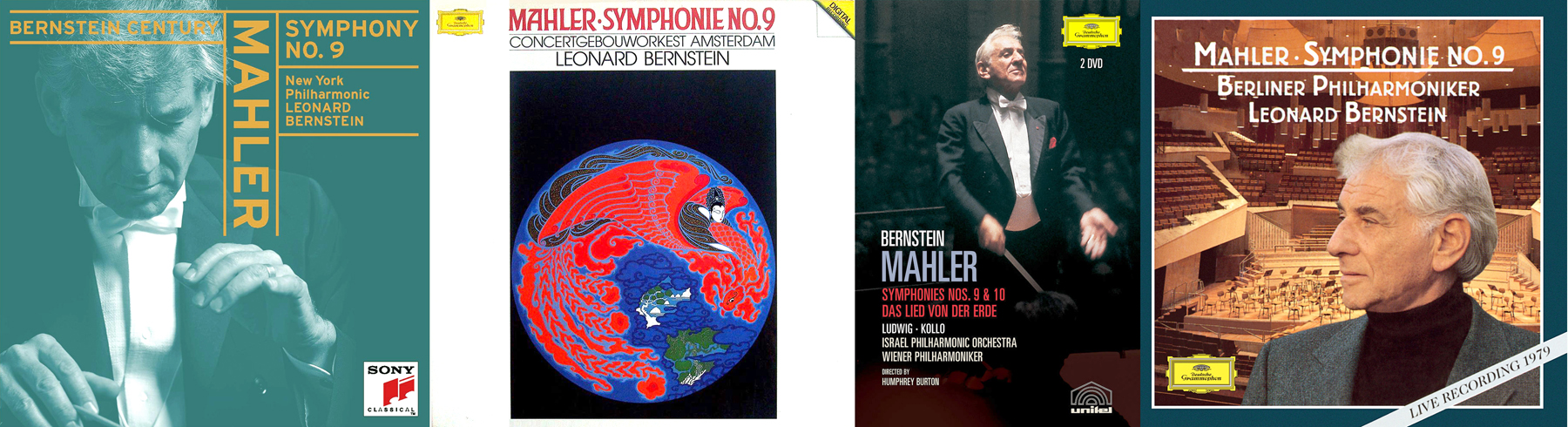

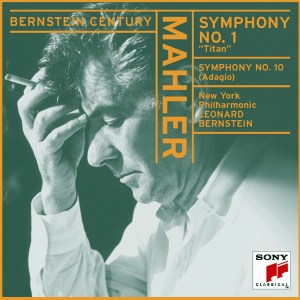

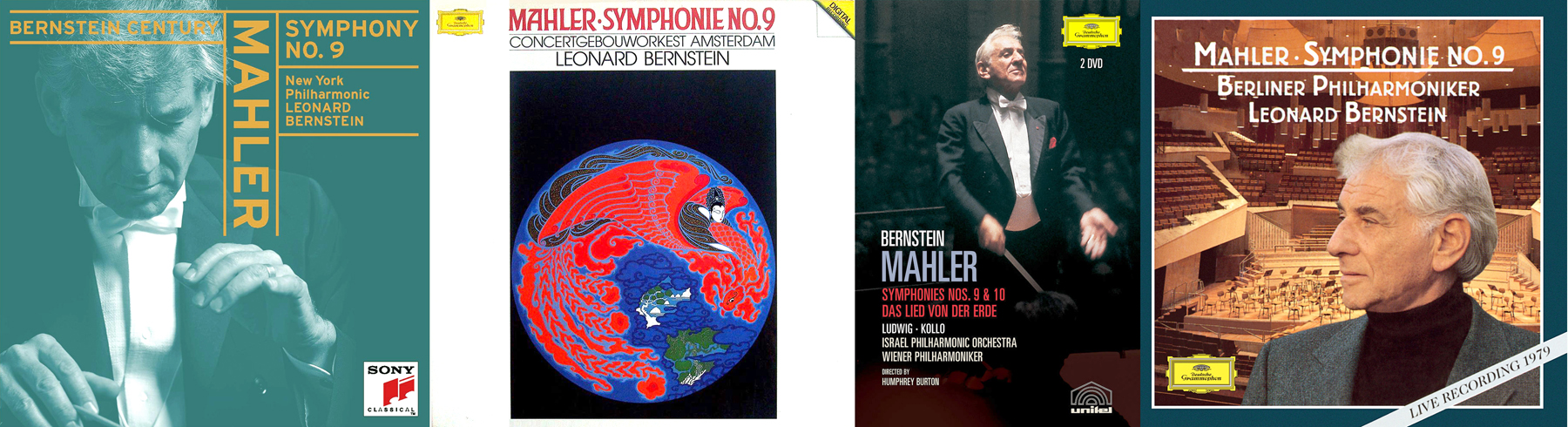

Bernstein made a meal of this symphony and recorded it four times, not counting a few live performances caught on tape outside the Bernstein canon. In the only time he ever performed with the Berlin Philharmonic, he recorded the Mahler Ninth. It is held in reverence by many, despite a glaring lapse by the trombone section in the finale (reputedly, an audience member sitting behind the section had a heart attack and died and the trombonists were understandably distracted). Even so, it is a powerfully emotional recording. But then, all of Lenny’s Ninths carry that wallop.

If you wish to escape the Bernstein reality distortion field, there are other tremendous Ninths. Barbirolli’s with the Berlin Philharmonic, from 1964, is a clear and unsentimental, but still emotional performance. Bruno Walter premiered the work in 1912, a year after Mahler’s death, with the Vienna Philharmonic. He made a stereo recording with the Columbia Symphony exactly 50 years later; that recording is a benchmark for many.

If you wish to escape the Bernstein reality distortion field, there are other tremendous Ninths. Barbirolli’s with the Berlin Philharmonic, from 1964, is a clear and unsentimental, but still emotional performance. Bruno Walter premiered the work in 1912, a year after Mahler’s death, with the Vienna Philharmonic. He made a stereo recording with the Columbia Symphony exactly 50 years later; that recording is a benchmark for many.

It has been recorded by almost every conductor out there, up to Bernard Haitink and the Royal Concertgebouw just last year.

The version I learned on was a surprisingly good version by Leopold Ludwig and the London Symphony, from 1960, on the old Everest label. I still enjoy his Ländler above most.

Symphony No. 10

Mahler never finished his Tenth Symphony, but left it in tantalizing form as piano short score. He did orchestrate the opening adagio, and until recently, the adagio was performed as a stand-alone. That piano sketch has been orchestrated since, essentially by committee, and there are now many full recordings out there.

Mahler never finished his Tenth Symphony, but left it in tantalizing form as piano short score. He did orchestrate the opening adagio, and until recently, the adagio was performed as a stand-alone. That piano sketch has been orchestrated since, essentially by committee, and there are now many full recordings out there.

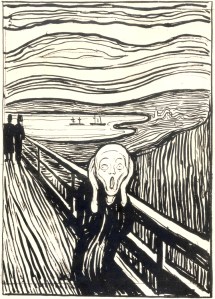

I have never been convinced by the attempted realizations of the whole, but the adagio is absolutely scarifying. It slowly builds up to a climax that is so frightening that in a good performance, your fight-or-flight hormones should get nightmares, the hair on the back of your neck should prickle and you should feel as if the gates of hell have opened and disgorged its contents. It is a scream of pain, an Edvard Munch level scream: “Ich fühlte das grosse Geschrei durch die Natur” (“I felt the great scream in nature.”)

Mahler had found out about Alma’s infidelity and he scribbled in his score several pained comments about it. He was devastated and the music shows it. At one point, nearly all twelve chromatic notes are played in a single harrowing dissonance, distributed across the orchestra in a way to make a musical chord rather than simply noise, and then a screaming trumpet breaks through the din to make things even more unbearable. After that moment, things go quiet and the movement continues to its distressed end.

Mahler had found out about Alma’s infidelity and he scribbled in his score several pained comments about it. He was devastated and the music shows it. At one point, nearly all twelve chromatic notes are played in a single harrowing dissonance, distributed across the orchestra in a way to make a musical chord rather than simply noise, and then a screaming trumpet breaks through the din to make things even more unbearable. After that moment, things go quiet and the movement continues to its distressed end.

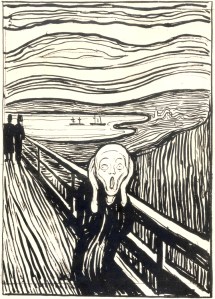

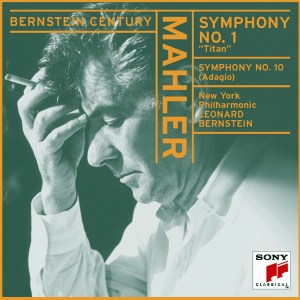

If you want to hear all five movements, there are many good performances, including Simon Rattle with the Berlin Philharmonic. But I will cling to the adagio alone and the first version I knew — Bernstein’s first with the New York Philharmonic. Any time the emotion is more to the point than the music, Bernstein conducts the emotion. This is Mahler at his most Mahlerian, and Lenny at his most Bernsteinian.

If you want to hear all five movements, there are many good performances, including Simon Rattle with the Berlin Philharmonic. But I will cling to the adagio alone and the first version I knew — Bernstein’s first with the New York Philharmonic. Any time the emotion is more to the point than the music, Bernstein conducts the emotion. This is Mahler at his most Mahlerian, and Lenny at his most Bernsteinian.

Das Lied von der Erde

After all that, if I were forced to accept having only a single work of Gustav Mahler, it would be Das Lied von der Erde (“The Song of the Earth”), a six-song cycle-symphony. Mahler had planned to publish it as his ninth symphony, but, superstitious about ninth symphonies (the final symphonies of so many composers), he refused to give it the title. When he then came to publish his next, he could name it the Ninth, knowing that fate would understand it was really his tenth.

But aside from that biographical titbit, Das Lied is an overwhelming and emotional work, even among an oeuvre that practically set the parameters for overwhelming and emotional.

But aside from that biographical titbit, Das Lied is an overwhelming and emotional work, even among an oeuvre that practically set the parameters for overwhelming and emotional.

Mahler’s output falls into three large groups. The first four symphonies are called his “Wunderhorn” symphonies, because they make use of his settings of songs from a book of poetry called Des knaben Wunderhorn (“A Boy’s Magic Horn”). The second group are his purely orchestral symphonies, numbers 4 through 7. The Eighth is sui generis and doesn’t count (see above). But the final three works, the Ninth Symphony, the trunk of the Tenth and Das Lied von der Erde are profoundly inward. You get the feeling that Mahler didn’t write them so much for audiences, but as a way to question his own existence.

The songs of this symphony are taken from a book of Chinese poetry, translated into German (or invented) called “The Chinese Flute.” The texts investigate beauty, isolation, nature and death, and where all these intersect. “Dunkel ist das Leben, ist der Tod.”

The sixth and final song — Der Abschied (“The Farewell”) — lasts as long as the first five and features some of the most ethereal orchestral writing Mahler ever penned, and a text that Mahler supplemented with several lines of his own.

“I seek peace for my lonely heart,” the contralto sings. And ends, “The dear Earth everywhere/ blooms in spring and grows green anew./ Everywhere and forever blue is the horizon./ Forever … Forever.”

That last word — “ewig” in German — repeats and repeats ever more silent, until it completely evaporates. It is impossible to hear it without sobbing.

The symphony was premiered by Bruno Walter in 1911, six months after Mahler’s death, and Walter recorded it at least three times, in 1936, 1952 and 1960, the last in stereo. Either of the last two can be considered the one to have: Each has its champions and both are magnificent and echt Mahler.

The symphony was premiered by Bruno Walter in 1911, six months after Mahler’s death, and Walter recorded it at least three times, in 1936, 1952 and 1960, the last in stereo. Either of the last two can be considered the one to have: Each has its champions and both are magnificent and echt Mahler.

But the one you cannot do without is by Otto Klemperer, released in 1967, with Fritz Wunderlich and Christa Ludwig. It has better sound than any of the Walters and magnificent singing. This is music right in Klemp’s wheelhouse.

Complete sets

Warning at the outset: No single set of complete recordings is great in all of the symphonies. But having a complete set gives you a consistent vision of what the work is all about.

Bernstein recorded them all three times. The first for Columbia (now Sony), mostly with the New York Philharmonic. The second for Deutsche Grammophon, mostly with the Vienna Philharmonic. And finally, a video set, on DVD, for Unitel, mostly with the Vienna Phil. The first two are canonic, and while each cycle has its proponents, you really should have both.

Bernstein recorded them all three times. The first for Columbia (now Sony), mostly with the New York Philharmonic. The second for Deutsche Grammophon, mostly with the Vienna Philharmonic. And finally, a video set, on DVD, for Unitel, mostly with the Vienna Phil. The first two are canonic, and while each cycle has its proponents, you really should have both.

Pierre Boulez is kind of the anti-Bernstein, cool and analytical, precise and controlled. For Boulez, Mahler is a 20th century composer — or at least a prefiguring, and the source of the Second Viennese School. You can hear every instrument with clarity

But is Mahler Mahler without going over the top emotionally? Klaus Tennstedt has many devotees, and falls more into the Bernsteinian camp. He recorded them with the London Philharmonic. It is a great set. I gave mine away, not because I didn’t like them, but because I gave them to my best friend; he deserved them.

But is Mahler Mahler without going over the top emotionally? Klaus Tennstedt has many devotees, and falls more into the Bernsteinian camp. He recorded them with the London Philharmonic. It is a great set. I gave mine away, not because I didn’t like them, but because I gave them to my best friend; he deserved them.

A sleeper among sets is David Zinman with the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich. It is the best engineered set I have heard and with beautiful playing by the orchestra.

There have been sets that mixed and matched conductors and orchestras. Both DG and Warners have great sets. Another, called the “People’s Edition” had a promotional vote to choose which recordings to include. The fact that each set chooses from their proprietary recordings means that there is no agreement on what are the best recordings. Everyone, after all, has their opinion. In Mahler-World, opinions are strong.

Other conductors have less-than-complete boxes out there. Klemperer only recorded Symphonies 2, 4, 7, 9 and Das Lied von der Erde. His No. 2 and Das Lied are consensus choices for best ever. The Seventh is just awful, but you should hear it anyway.

Hermann Scherchen has a box with all but the Fourth and no Das Lied. He recorded with second-rate orchestras, for the most part, and is often so wayward his interpretations have been called “Variations on Themes by Mahler.” The sound engineering is highly variable. This one is for specialists only.

In the BB list (“Before Bernstein”), you get to hear all nine symphonies with Ernest Ansermet and the Utah Symphony and hear what they sound like before the current Mahler Tradition was assembled (largely by Lenny). They are surprisingly good, and you get a different slant on the music (less peculiar than Scherchen’s).

Benjamin Zander and the Philharmonia has not yet recorded the Seventh or Eighth, but the rest are among my favorites and I listen to them often. More than any other conductor, Zander follows Mahler printed directions accurately, and brings out expressive details glossed over in other recordings. There are those who disparage Zander for this detail orientation, but for me, it is the heart of a Romantic interpretation. This is the way they were played under Mahler, I am convinced. I love them all. And each comes with an hour-long lecture, explaining many of the details. He is a great speaker as well as conductor.

Benjamin Zander and the Philharmonia has not yet recorded the Seventh or Eighth, but the rest are among my favorites and I listen to them often. More than any other conductor, Zander follows Mahler printed directions accurately, and brings out expressive details glossed over in other recordings. There are those who disparage Zander for this detail orientation, but for me, it is the heart of a Romantic interpretation. This is the way they were played under Mahler, I am convinced. I love them all. And each comes with an hour-long lecture, explaining many of the details. He is a great speaker as well as conductor.

There are others: Chailly, Bertini, Gielen, Sinopoli, Rattle. And all have their merits.

The sets just keep coming. Everyone gets into the act. I have not been anywhere near complete.

But these are the ones I have come to love. And, of course, there are many individual recordings, not part of sets. And many of these are among the greatest.

And I have not even mentioned the other song cycles. Maybe another time.