Ludwig van Beethoven would have turned 244 this week.

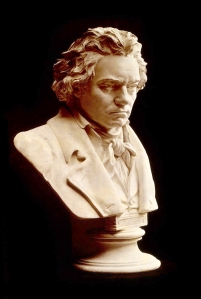

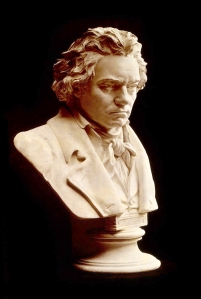

Everyone knows Beethoven. He wrote “Da-da-da-dum” and “Ode to Joy.” He’s the scowling visage parodied by John Belushi on Saturday Night Live. He’s the plaster bust on Schroeder’s toy piano.

Ask anyone to name a classical music composer and nine out of 10 will utter his name. Even those with no familiarity with classical music know he’s the one who rolls over to tell Tchaikovsky the news.

So it’s not surprising that symphonies program his music more than anyone else’s, and often devote entire festivals to the music.

It would be silly to call anyone the “greatest” composer, but Beethoven — along with only Bach — is the one most often given that honor. Such is his power as a producer of human emotion through the ear canal, that his only real rivals in European art music are Bach and perhaps Mozart. That doesn’t mean he is everyone’s favorite composer. There are many who cannot stand his relentless pounding and drive. And surely among “great” composers, Beethoven probably has the third-most detractors, after Schoenberg and Wagner.

But it would be hard to find anyone who has altered Western music history more directly and obviously than the scowling master from Bonn.

“There are many reasons one could say Beethoven’s music is the greatest. His music speaks to the listener from the first note,” says conductor Michael Christie, music director of the Minnesota Opera.

It isn’t just that the music is familiar, it’s overpowering. It’s big, loud, sublime and of an intensity unheard before him.

“Just take the opening of the ‘Eroica’ symphony,” conductor Joel Revzen says. “The first two chords. Haydn or Mozart used a slow introduction to prepare us for what is to come. Beethoven takes a hammer and hits you over the head with it.”

Two crisp E-flat chords, and we’re off to the races.

“You can listen to one chord and know it’s Beethoven,” conductor James Sedares says. “He had a voice that was completely unique for his time and always.”

Violinist Steven Moeckel has given wonderfully insightful performances of Beethoven’s violin concerto.

“This may sound cheesy, but it feels, when you play it, Beethoven got a glimpse of heaven. Audiences are taken on this journey, so epic. Beethoven is on a heroic scale — and he means to be.”

Difficult to appreciate

But why does Moeckel qualify it? “It may sound cheesy … . ”

There are several things that stand between us and Beethoven, and make both the performance and appreciation of his music difficult.

Beethoven’s music is about big ideas, such as heroism, nobility, struggle, brotherhood. He believed in them; the question is, do we? Or have such ideas been rendered into toothless bromides and platitudes?

Can we still understand Beethoven’s music after the trenches of World War I, after Auschwitz, after all the dehumanizing misery of the 20th century?

Music historian Richard Taruskin has written about the difficulty of accepting the grand vision of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with its paean to universal brotherhood.

“Why? Because it is at once incomprehensible and irresistible, and because it is at once awesome and naive,” he wrote.

“We have our problems with demagogues who preached to us about the brotherhood of man. We have been too badly burned by those who have promised Elysium and given us gulags and gas chambers.”

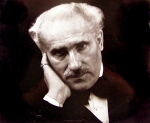

You can hear the problem in many modern performances of Beethoven. The conductor no longer believes in the grand ideas and falls back instead on the music’s obvious rhythm and drive. There’s a great divide between the conductors who performed before World War II and those who came after.

“I look for the old depth and breadth of expression that was there and can be retrieved if we listen to the right master,” the late conductor James DePreist said. “And most of the right masters are dead.”

You listen to recordings by Wilhelm Furtwangler or Willem Mengelberg and you hear a Beethoven different from that of Roger Norrington or David Zinman.

To many modern ears, the older performances seem melodramatic and overwrought. The modern performances seem cleaner and less fussy. The older conductors interpreted the music and massaged its rhythms. They conducted by phrase length, not by bar length, and they knew the rhetoric of performance and often spoke to their orchestras about the philosophy and meaning of the music. Modern conductors speak of the notes.

But Beethoven was clear about this. In the same way a great actor interprets Shakespeare when performing as Hamlet, and makes pauses and emphases, the musician was asked by Beethoven to do the same.

“The poet writes his monologue or dialogue in a certain continuous rhythm, but the elocutionist, in order to ensure an understanding of the sense of the lines, must make pauses and interruptions at places where the poet was not permitted to indicate it by punctuation,” Beethoven told his friend Anton Schindler. “The same manner of declamation must be applied to music.”

‘Writing for history’

But ours is an unheroic age. We reserve the word for firemen and soldiers, who certainly perform courageous acts. But a hero is more than that. Mythologically speaking, a hero is the individual who translates the will of the gods into history.

This is no small claim: A hero changes the world. Beethoven certainly did.

There is good reason to be suspicious of such things now. Too many have changed the world for the worse.

But Beethoven, born in Bonn, Germany, in 1770, clearly saw himself as a hero. He knew he was changing the world. He championed freedom and democracy in a restricted and aristocratic age.

“He changed the world of music,” conductor Lawrence Golan says. “Right off the bat, with the first chord of his first symphony. It was revolutionary at the time.”

He performed for the aristocracy and slummed with the nobility, but he told Schindler, “My nobility is here,” pointing to his heart, “and here,” pointing to his head.

“We’re clearly looking at big ideas in Beethoven’s music,” conductor Timothy Russell says. “Mozart wrote for an audience, but Beethoven knows he’s writing for history.”

History, however, has moved on.

Disposable music

For the 21st century, music has mostly become entertainment. Music written to be pondered and meditated upon does not fit into the jigsaw puzzle of a niche-market audience, where music is used and discarded in months.

“Beethoven wrote Velcro music and this is a Teflon Age,” DePreist says.

“We have deconstructed the 19th century and have an initial impulse to jettison so much of it. But the idea that the 20th century — or the 21st century — would simply supplant the 19th was absurd,” he says. “But we have much to learn from every century.”

The difficulty has been to separate the desire to be free from the past — which is an honest desire — from the tendency to ignore the past and refuse to look at what the past teaches us.

“It teaches us more than the notes of the stylistic things,” DePreist says.

Art has a responsibility to challenge people, says Moeckel.

“To broaden their horizons, and, so, if you don’t like it, that’s fine, but let’s talk.”

And what he confronts us with is the struggle of being alive.

“Beethoven was a man who struggled every day of his life, a man shaking his fist at the heavens constantly,” says Revzen. “It is the human condition to struggle against adversity, whether socially, politically or one’s physical limitations. It is the struggle of the human condition through eternity.”

If you want to relate it to the contemporary world, he says, just think of what the people in in Syria or Afghanistan are going through just to survive, “or the people who struggle against oppression every day around the world, or the people who struggle in this recession.”

“How can I survive until tomorrow in hopes maybe my life will change?”

It is that engagement with the big things that drives Beethoven’s music and gives it such power to move us, even when we are suspicious of its meaning. The problem is ours, not Beethoven’s.

“There is still a message in the ‘Eroica’ or the ‘Ode to Joy,’ ” conductor Benjamin Rous says.

“Our time is broken in a way Beethoven’s music isn’t. Maybe a broken era needs an art that is whole.”

Three creative periods

Critics, biographers and historians divide Beethoven’s life and work into three periods: early, middle and late.

Since Beethoven, the tripartite division has come to fit the careers of many artists, but it began with the composer.

His Early Period features music that imitates the style of Haydn and Mozart, and although the music sometimes strains to escape the bonds of that style, it’s thoroughly Classical.

His Middle Period contains most of the music for which he’s best loved: the “Eroica” symphony, the “Emperor” concerto, the “Archduke” trio, the “Appassionata” sonata. It is big, brawny, heroic music that strains to escape not just the style but the very limits of the musical instruments of his time, the philosophical and religious conventions of his era, and sometimes the very heart in his breast. It is loud, pounding music.

“He grabs you by the collar and says, ‘I’m Beethoven, and I have something to say!’ ” says Revzen.

There are a lot of musical exclamation points in this very publicly aimed music.

It is in the Middle Period that Beethoven staked his claim to being the first Romantic composer, emphasizing emotion over formal restraint. But, as conductor Benjamin Rous puts it, “He started out as Classical and ended up as Romantic, but in reality, he was Classical and Romantic at every moment in his life.”

Finally, Beethoven’s Late Period defines the term for all others: The music becomes more inward and searching, it has left behind the formal constraints of the time and experiments with new form, new meaning and expression. His late quartets bewildered not only the audiences of his time but the musicians who played them.

“Do you imagine, when the spirit speaks to me, I have your wretched fiddle in mind?” he asked violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh, whose string quartet premiered most of Beethoven’s late quartets.

Beethoven’s late music remains a challenge for many listeners. The “Grosse Fuge,” was his final movement to the string quartet op. 130, but was a movement so difficult for both listeners and performers that when Beethoven originally submitted it for publication, his publisher requested he substitute something easier. It is still work to listen to, albeit work with a tremendous payoff to those willing to dive in.

The rondo he wrote in its place as the quartet’s finale turned out to be the last piece of music Beethoven wrote before his death.

A gut reaction

Ludwig van Beethoven was probably history’s most famous sufferer of irritable-bowel syndrome. It made the composer’s life miserable and likely accounts for the scowl he wears in almost every portrait.

“The cause of this must be the condition of my belly which, as you know, has always been wretched and has been getting worse, since I am always troubled with diarrhea, which causes extraordinary weakness,” the composer wrote a friend in 1801.

It was a problem that plagued him his entire life, and its likely cause is what killed him.

This may seem an undignified way to introduce “the greatest composer in history,” but you have to do something to clear away the idolatry that accumulates around a world-changing figure, to see him as a man rather than a demigod.

Otherwise, when we spin panegyrics about the man’s greatness, our eyes will glaze over, reading it as conventional boilerplate.

So, it must be said that this colossus who changed music and directed its course for more than a century was in reality a short, stocky German with a provincial accent, boorish manners, who wrote in bad grammar and frequently uttered banal platitudes as if they were earth-shaking profundities.

He was born in Bonn in 1770, and his drunken father tried to pass the child off as a prodigy, like Mozart. But Beethoven’s virtues were not Mozart’s: He had none of the grace and felicity of Mozart; his music grew from hard work and infinite rewriting.

Beethoven went to Vienna to make his fortune as a piano virtuoso and found many aristocratic patrons. He frequently insulted the hand that fed him.

He told one of his patrons, “Prince, what you are, you are by accident of birth; what I am, I am through my own efforts. There have been thousands of princes and will be thousands more; there is only one Beethoven!”

But just as he began to achieve fame, his hearing started to fail. In later years, he was completely deaf: At the premiere of his Ninth Symphony, a soprano had to turn him around onstage so he could see the applause he could not hear.

Each new piece found both acclaim and criticism: Conservatives disliked the profusion of ideas in the music, finding them confusing and the works too long and difficult; admirers recognized in his work overwhelming emotional power.

By the time of his death, in 1827 at the mere age of 56, he was generally acclaimed as the greatest composer in the world. More than 20,000 people attended his funeral.

It is only in recent years, after scientific analysis of a few strands of his hair, that we know how the composer died: It was lead poisoning, probably by drinking wine from a lead-lined cup, that slowly killed the composer and probably caused his lifetime of colic.

The ‘Mighty Nine’

Beethoven’s nine symphonies are the cornerstone of classical music. Every conductor cuts his teeth on them; every audience expects them.

Their monumentality influenced every composer who came after him for at least a century, and even now, it’s impossible to dip into classical music without addressing “The Nine,” as they’re known.

But the symphonies are very distinct; each has its own personality. Collectively, they are probably the best entry point for discovering the music of the titan, Beethoven.

There are many sets of them on CD, spanning nearly the entire history of recorded music. The first complete set of symphonies was recorded in 1920 and since then there have been at least 100 traversals. There have been 60 full sets sold since 1960. Herbert von Karajan recorded them all four times, Bernard Haitink and Eugen Jochum each did it three times. Any conductor worth his salt wants to prove his mettle by tackling the nine.

There is no one “best” set — pretty much everyone is agreed on that point — but if you want them all in one package, you could hardly to better than the set with Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin recorded on Teldec. Both the performance and engineering are tops. Teldec makes the orchestra sound like it’s in your room with you. Barenboim has a unified and coherent view of the cycle which is intelligent and emotionally persuasive.

But for some, it will feel old-style. It is. If you want the modern huff-and-puff race to the finish, then you should look to John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique on so-called original instruments.

You could hardly find two more different views of the music, but both are played with commitment and musicality. (Avoid the Norrington sets, which are dreadful and downright unmusical).

One-by-one

There are many who insist the best way to acquire the best of them is to get them individually and not in complete sets. Different orchestras and different conductors respond to certain symphonies better than others. David Zinman and the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, for instance, cannot be beat for discovering the wit and verve in Beethoven’s first symphony, but they don’t really believe in the nobility and heroism inherent in the bigger, odd-number symphonies, like the Fifth. For that, you have to go to an old-order conductor, such as Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Berlin Philharmonic, which recorded the most harrowing and emotionally wrought versions of the Fifth Symphony.

Any choices among the symphonies will be idiosyncratic: As listeners we are just a variable in our sympathies as the conductors themselves. You may want the bounce and beat of a modern performance, or you may be more moved by the old tradition.

These are a few of my suggestions, along with some information about each of the Nine.

Please note that modern critics aren’t the only ones who are idiots.

Symphony No. 1 in C

First performed: 1801.

Beethoven’s first is his lightest, brightest and funniest, an obvious imitation of the spirit of his teacher, Joseph Haydn. Its jokes begin with the very first notes: a dissonance in the wrong key!

Beethoven’s first is his lightest, brightest and funniest, an obvious imitation of the spirit of his teacher, Joseph Haydn. Its jokes begin with the very first notes: a dissonance in the wrong key!

Initial critical response: One critic called it “a caricature of Haydn pushed to absurdity.”

Suggested recording: No one has captured the wit of this symphony better than David Zinman and the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich.

Symphony No. 2 in D

First performed: 1803.

Now considered one of Beethoven’s “shorter, lighter” symphonies, it was a large symphony by the standards of the time and a challenge for its first audience.

Now considered one of Beethoven’s “shorter, lighter” symphonies, it was a large symphony by the standards of the time and a challenge for its first audience.

Initial critical response: The Leipzig critic called it “a gross enormity, an immense wounded snake, unwilling to die, but writhing in its last agonies, and (in the finale) bleeding to death.”

Suggested recording: Bernard Haitink and the London Symphony.

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat, “Eroica”

First performed: 1805.

This immense symphony single-handedly changed the course of music history; twice as long as the standard Haydn symphony and built on ideas of heroism, with a great funeral march as a slow movement.

This immense symphony single-handedly changed the course of music history; twice as long as the standard Haydn symphony and built on ideas of heroism, with a great funeral march as a slow movement.

Initial critical response: The leading music journal of the day described it as “a daring wild fantasia of inordinate length and extreme difficulty of execution. … There is no lack of striking and beautiful passages in which the force and talent of the author are obvious; but, on the other hand, the work seems often to lose itself in utter confusion.”

Suggested recording: Many modern performances are too tame. For the needed heroism and grandeur, and the sheer visceral excitement, try Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic.

Symphony No. 4 in B-flat

First performed: 1807.

Robert Schumann called it a “graceful Grecian maiden between two Norse giants.” It seems like a retreat after the furious charge of the “Eroica,” but if it is less noisy, it is subtly subversive, with an introduction in the “wrong” key.

Robert Schumann called it a “graceful Grecian maiden between two Norse giants.” It seems like a retreat after the furious charge of the “Eroica,” but if it is less noisy, it is subtly subversive, with an introduction in the “wrong” key.

Initial critical response: Carl Maria von Weber wrote a review in which the orchestra instruments all bitterly complain about having to play this symphony and then are threatened with being forced to play the “Eroica” if they don’t shut up.

Suggested recording: Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic are as elegant as it gets.

Symphony No. 5 in C-minor

First performed: 1808.

For two centuries, this has been Beethoven’s calling card, the primal symphony, restless, turbulent, an epic struggle to wrest a triumphant C-major out of an obsessive C-minor, and with more than 700 relentless iterations of the iconic rhythm: “Da-da-da-dum.”

For two centuries, this has been Beethoven’s calling card, the primal symphony, restless, turbulent, an epic struggle to wrest a triumphant C-major out of an obsessive C-minor, and with more than 700 relentless iterations of the iconic rhythm: “Da-da-da-dum.”

Initial critical response: French critic Jean Lesueur said it was such exciting music that it shouldn’t even exist.

Suggested recording: The music is so familiar, and so emotional, it’s hard to play now without irony, but when attacked with conviction, it still packs a wallop. Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Vienna Philharmonic are still the champs in a pre-stereo recording, but in modern sound, Carlos Kleiber and the same orchestra come very close.

Symphony No. 6 in F, “Pastoral”

First performed: 1808.

This is Beethoven’s musical picture of nature, complete with birdcalls and thunderstorm. But it’s also one of the composer’s most tightly argued pieces musically, with much of the symphony drawn from the first two bars: It’s a miracle of concision, even when most discursive.

This is Beethoven’s musical picture of nature, complete with birdcalls and thunderstorm. But it’s also one of the composer’s most tightly argued pieces musically, with much of the symphony drawn from the first two bars: It’s a miracle of concision, even when most discursive.

Initial critical response: Berlioz agreed with critics, “as far as the nightingale is concerned: the imitation of its song is no more successful here than in M. Lebrun’s well-known flute solo, for the very simple reason that since the nightingale only emits indistinct sounds of indeterminate pitch it cannot be imitated by instruments with a fixed and precise pitch.”

Suggested recording: Every critic’s choice in this seems to be Bruno Walter and the pickup Columbia Symphony Orchestra.

Symphony No. 7 in A

First performed: 1813.

Richard Wagner called this the “apotheosis of the dance,” and it is the most rhythmically driven of all symphonies; the second movement hardly contains anything but its rhythm. It all comes together in a Dionysian paean to the spirit of life.

Richard Wagner called this the “apotheosis of the dance,” and it is the most rhythmically driven of all symphonies; the second movement hardly contains anything but its rhythm. It all comes together in a Dionysian paean to the spirit of life.

Initial critical response: Weber expressed the opinion that Beethoven “was now ripe for the madhouse.”

Suggested recording: Even though it’s a pre-stereo recording, you have to hear Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony in a driven performance that wrests every ounce of power out of the score.

Symphony No. 8 in F

First performed: 1814.

The composer looks backward with a smaller, almost Haydnish symphony, full of Haydnesque “jokes,” such as the metronome tick-tick of the second movement.

The composer looks backward with a smaller, almost Haydnish symphony, full of Haydnesque “jokes,” such as the metronome tick-tick of the second movement.

Initial critical response: One critic wrote that “the applause it received was not accompanied by that enthusiasm which distinguishes a work which gives universal delight; in short — as the Italians say — it did not create a furor.”

Suggested recording: Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony give a brawny performance of this work and include a really fine Symphony No. 7 as well.

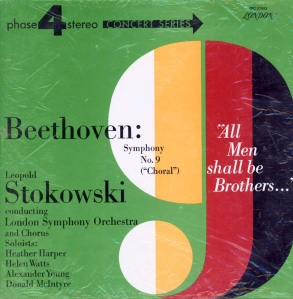

Symphony No. 9 in D-minor, “Choral”

First performed: 1824.

Beethoven’s magnum opus, which adds singers and chorus to the symphony and expresses the composer’s view of universal brotherhood and the joy of the cosmos. At more than an hour long, it is immense and usually performed for ceremonial occasions.

Beethoven’s magnum opus, which adds singers and chorus to the symphony and expresses the composer’s view of universal brotherhood and the joy of the cosmos. At more than an hour long, it is immense and usually performed for ceremonial occasions.

Initial critical response: “Beethoven is still a magician, and it has pleased him on this occasion to raise something supernatural, to which this critic does not consent.”

Suggested recording: Despite mangling the finale by changing Beethoven’s “Freude” (“joy”) to “Freiheit” (“freedom”), there is no more committed performance than the one given by Leonard Bernstein at the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 with an orchestra composed of musicians from many orchestras in both East and West Germany.

hear. It is buried under a welter of excited sound. When the chorus sings its final “Götterfunken” at the end of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the coda that follows builds up steam quickly and drives home to a final D major chord. It is in the final chords that Beethoven hides an extra fillip: He has his fiddles, which are already racing as fast as they can go, double the number of notes they have to play — dig-ga-dig-ga to diggadada–diggadada — and the tympani doubles its speed, too. This detail is usually buried in the overwhelming drive of the rest of the orchestra, but one recording makes the change clear: a 1967 recording by Leopold Stokowski and the London Symphony, originally released on a London Phase 4 LP, with singers Heather Harper, Helen Watts, Alexander Young and Donald McIntyre. Its drive is overwhelming.

hear. It is buried under a welter of excited sound. When the chorus sings its final “Götterfunken” at the end of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the coda that follows builds up steam quickly and drives home to a final D major chord. It is in the final chords that Beethoven hides an extra fillip: He has his fiddles, which are already racing as fast as they can go, double the number of notes they have to play — dig-ga-dig-ga to diggadada–diggadada — and the tympani doubles its speed, too. This detail is usually buried in the overwhelming drive of the rest of the orchestra, but one recording makes the change clear: a 1967 recording by Leopold Stokowski and the London Symphony, originally released on a London Phase 4 LP, with singers Heather Harper, Helen Watts, Alexander Young and Donald McIntyre. Its drive is overwhelming.