I was born in the upper right corner of New Jersey, just to the west of the Hudson River and a few miles south of the New York state line and the Rockland State Hospital, an asylum famous for once housing Allen Ginsberg and Carl Solomon.

That corner of the map is Bergen County, the most populous county in the state and where I spent the first 17 years of my life, before I managed to escape. It is unrelentingly suburban and, to my young sensibility, numbingly banal. In my senescence, six decades later, I have moderated my disdain and now recognize it as my hatchery — and a part of my psyche that I cannot ever fully extirpate. Like Quentin Compson speaking about his native Mississippi, I can say of my own native state, “I don’t hate it. I don’t. I don’t hate it.”

The Hackensack River

Bergen County is split by two rivers, the Hackensack and the Passaic. The later forms part of the western border of the county and the Hackensack ran through the town where I was raised and drained, finally, into Newark Bay to the south, between Newark and Jersey City, two old cities that show their age.

To the east of the Hackensack, the land rises abruptly until it reaches an edge high above the Hudson River, called the Palisades, a 20-mile long series of basalt cliffs that rise to 500 feet above the water. This bit of America, from Paterson to Manhattan is the landscape of my Umwelt — etched into my psyche.

Since I grew up there and knew no better, I assumed that all rivers must be as wide as the Hudson, and when I first came South to go to college, was less than impressed with what passes for a river there. The Deep River, near my Guilford College, I could have jumped across. That’s not a river, that’s a brook (or, in Southern parlance, a creek).

But the Hudson was noble, wide and impressive. Historically, it ran through the home land of the Lenape Indians and the county is filled with towns and rivers given versions of their Indian names, including my home town, Old Tappan, which was named for the Tappan tribe of Lenape people, which may mean “cold water.” All of New Jersey and parts of Pennsylvania, Delaware and New York were originally Lenape lands.

Other Bergen County Native American names, however twisted by the ears of the early colonists, include: Hackensack; Ho-Ho-Kus; Mahwah Moonachie; Paramus; Teaneck; and Wyckoff.

Names can get quite twisted. In central Jersey the name of Cheesequake was originally the Lenape name Chiskhakink, which meant “cleared land.” Other New Jersey names, some harder to pronounce than others, at least for non-native Jerseyites, include Hoboken, Hopatcong, Manahawkin, Mantoloking, Metuchen, Neshanic, Netcong, Pahaquarry, Parsippany, Pequannock, Piscataway, Ramapo, Secaucus, Squankum, Succasunna, Weehawken, Wickatunk. And that doesn’t count the lakes, rivers and creeks: Absecon; Assunpink; Assiscunk; Hakihokake; Hockhockson; Kittatinny; Luppatatong; Machesautauxen; Metedeconk; Muksukemuk; Musconetcong; Picatinny; Pohandusing; Rancocas; Shabakunk; Waackaack; Wawayanda; Wickecheoke — and that’s about 10 percent of the list. I believe I’ve heard my cat say “Waackaack” at times.

If you’re from there, these names roll easily off the tongue, if not, well — I once heard a newscaster pronounce Parsippany as “par-suh-PAN-ee.”

Then, there’s Kinderkamack Road, which sounds like it should be among the many Dutch names in the area, but is really a version of the Lenape for “Place of the Ceremonial Dance.” But you would be forgiven for mistaking it. After the Native Americans came the Dutch, with their own names for things, such as Kill van Kull, Polifly, Paulus Hook, Schraalenburgh, and Tenafly.

There’s a lot of history in New Jersey, although most Jerseyites pay little attention to it. Not only Native American and Dutch history, but New Jersey was once a slave state. My county, Bergen, was the largest holder of enslaved people in New Jersey, with 20 percent of its population in bondage in 1800. New Jersey was the last of the Northern states to outlaw slavery. At the end of the Civil War, there were about a dozen slaves still owned in the state, eventually freed by the 13th Amendment. By the way, the state voted against Abraham Lincoln both in 1860 and in 1864.

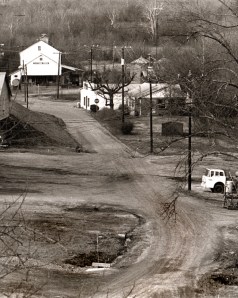

When my father was clearing land in our back yard in Old Tappan, he dug up an old brick foundation that a local historian identified as the remains of an 18th century slave quarters.

The stony ground of the state has seen a lot of history. One of the most famous and consequential battles of the Revolutionary War was fought in Jersey, as George Washington crossed the Delaware River in the winter of 1776 and surprised British forces at Trenton. He did it again a year later.

During the Gilded Age, New Jersey was a comfortable home for corporate monopolies. Before being broken up by the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in 1911, Standard Oil of New Jersey had controlled nearly 90 percent of refined oil in the United States.

Oh, New Jersey. Wikipedia lists more than 50 New Jersey politicians convicted of crimes and corruption, most famously in recent years, Sen. Bob Menendez, who was found guilty of taking bribes after investigators found Menendez had illegally received a Mercedes-Benz car, 13 gold bars, and $486,461 in cash.

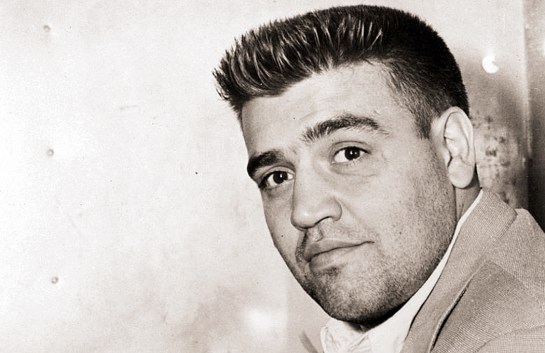

The Chin

In my own home town of Old Tappan, Mafia boss Vincent “The Chin” Gigante had a house a little more than a hundred yards from where I grew up. I didn’t know that at the time, but imagine my surprise when, at college in 1970, I turned on the radio one morning and heard the NPR announcer say that the entire police force of Old Tappan had been arrested for taking cash from Gigante’s wife, Olympia.

Other high points in New Jersey history:

It was the home, in Menlo Park, to Thomas Edison’s research laboratory, later moved to West Orange.

New Jersey was the first state to ratify Prohibition.

In 1927, the Holland Tunnel connected NJ to Manhattan, followed by the George Washington Bridge in 1931 and the Lincoln Tunnel in 1937.

In 1932, the baby of Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow was kidnapped from their home in Hopewell, NJ., and later found dead. A nation-wide manhunt eventually led to the arrest two years later of Bruno Hauptmann, who was convicted of and executed for the crime.

The dirigible airship Hindenburg, a German Zeppelin, exploded in flames upon landing at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in 1937, killing 13 passengers and 22 crewmen. “Oh, the humanity!”

In the infamous Mercury Theatre War of the Worlds radio broadcast of 1938, Orson Welles claimed that Martians had landed in Grovers Mill, NJ.

And on Sept. 23, 1949, Bruce Springsteen was born, in Long Branch, on the Jersey shore.

The state tends to get divided into three parts, Northern Jersey, Central and South Jerseys. The north is all suburbs of New York City; the south is oriented to Philadelphia and Central Jersey is orphaned between.

But really, there is another way of splitting up the map that is more reflective of the cultural realities. There is suburban and industrial New Jersey, which is a ribbon running from the northeastern part of the state and cuts diagonally across to the southwest, near Philly. This includes not only my Bergen County, but also Newark, Trenton, Camden, and the Oranges — pronounced locally as Onch, East Onch, South Onch, and West Onch. There is no Nawt Onch.

The second part might be considered Appalachian New Jersey and is in the northwest, largely rural and wooded, with the Kittatinny Mountains and the Delaware Water Gap. My summer Boy Scout camp was there, where I was first camper and later camp counselor.

The third part of the state might be called Confederate New Jersey, technically below the Mason-Dixon Line and composed of farm land, swamps and the infamous Pine Barrens, supposed home to the Jersey Devil, a legendary flying demon, said to have been born in 1735 as the 13th child of local woman Deborah Leeds. The child, though born normally. immediately grew wings, tail, and claws and flew out to the Pine Barrens, where, like Big Foot, it is occasionally claimed to have been spotted.

South Jerseyites can even speak with a drawl, separating them culturally from those farther north. The familiar Joisey accent has a pronounced rising “dawg” while in the south, they are closer to a descending “doag.” (The North Jersey accent is quite distinct. We once had a plumber come to fix our “terlet.”)

There is a fourth important component to the state. Some consider it part of South Jersey, but it is distinct enough — and famous enough — to warrant its own regional name. It runs down the eastern margin of the state, from Sandy Hook to Cape May and it is the Jersey Shore. It is not like any other section of the state and has gained notoriety for the empty-brained drunkenness and pointlessness of the MTV “reality” television program. The less said, the better.

The broad stripe that runs diagonally down the center of the state is the heart of what people think of as being New Jersey. Bergen, Hudson, Essex, Union, Middlesex, Mercer, Burlington, Camden and Gloucester counties and parts of others, are both the suburban and industrial centers of the state, and the source of most of the enduring cliches.

But it is the center filet that has all the housing developments, mcmansions, oil refineries and chemical plants — to say nothing of the Pulaski Skyway and the single most trenchant metaphor for the state: The NJ Turnpike. (“Where do you live?” “Exit Four.”)

When I left New Jersey as a teenager headed off to college in North Carolina, I shook the dust off my sandals and said good riddance. I despised the bourgeois banality of it all and couldn’t wait to get to the “real” stuff that higher education would show me: art and poetry and music, and — well, beer and sex. But over the years I came to realize both that New Jersey was not exceptional in its inanity — that was everywhere — and also more importantly, I had to accept that New Jersey had built my insides.

The pace, the smells, the population density, the architectural styles, the speech, the ethnic and religious diversity I had known had all become the universal norms by which I judged the world.

It came as a shock, for instance, that there were so many churches and so few synagogues in the South. In Old Tappan, there was one Protestant church and one Catholic church and the nearest synagogue was in Closter. Here in my neighborhood in Asheville, there are three churches all in walking distance. Oy.

The Trinity Reformed Church in Old Tappan was presided over by the soft-spoken Louis Springsteen whose basic message to the congregation was that good is better than evil because it’s nicer. No brimstone, no hellfire. My Catholic friends went to St. Pius X at the other end of Cripplebush Road. Some of them went to parochial school and were taught by nuns. It was all just normal, and built that normal into me. Religion made no more difference to me or my friends than hair color or freckles.

I remember my father, raised in Cliffside Park, NJ, telling us that when he was drafted at the beginning of World War II and shipped off to Camp Wheeler in Georgia, he was shocked to find out the camp was segregated. The idea had never occurred to him.

And when I was at college a group of us decided to crash a Ku Klux Klan meeting in Liberty, NC, where the main speaker was the sheriff of Forsyth County, and I was surprised to find out that among the enemies they despised were not just Black folk, but Catholics and Methodists as well. Huh? Humanity never seemed such a narrow concept where I came from.

My Boy Scout troop was presided over by Paul Weinstein and his two assistants, Vern Riportella and Arch Curry. Basically, one of each.

It all, good and bad, became the unexamined bedrock of my personality. I remain somehow in New Jersey, even though I haven’t lived there in 60 years.

The highways I knew in Paramus seemed the normal highways; the shopping malls the size of Delaware were the norms; the traffic was normal; the oil refineries burning off their excess in the night sky was normal; the bus service, the delicatessens, the pizza, were all the baselines I took elsewhere with me.

I mean, come on — you call that a pastrami sandwich?

And New Jersey set the inner tick-tock of my sense of time, a quicker pace. As I’ve aged, the clock has slowed a bit, and living in the South for the majority of my life has moderated the tempo, but it still moves too fast for some. My Anne complains that I talk too fast, according to her North Carolina metronome.

Perhaps it is because my New Jersey innards prompts me more to favor efficiency than courtliness.

And while I grew up thinking of my home state as intellectually stultified, I have to grant that there are random points of light. I hesitate to include James Fenimore Cooper among them, after reading Mark Twain’s “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses” — “Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.” — but New Jersey was also the adopted home of Walt Whitman and the very subject and marrow of the poems of William Carlos Williams. There were also Stephen Crane, John Ciardi, Joyce Kilmer, Philip Roth, Amira Baraka (aka LeRoi Jones), George R.R. Martin, to say nothing of the Ginsbergs, père et fils. The Jersey Shore town of Long Branch alone has given us Springsteen, Norman Mailer, Robert Pinsky, and Dorothy Parker.

Springsteen, Pinsky, Mailer, Parker

New Jersey gave birth to, or was home to George Antheil, Gerard Schwarz, Astrid Varnay, Eileen Farrell, Dorothy Kirsten, Jerome Hines, Sherrill Milnes, Michael Tree, Stephen Paulus, Judith LeClair, and one-third of the Beaux Arts Trio. And that’s not even counting Count Basie or Frank Sinatra.

And visual artists: Charles Addams, John Held Jr., George Platt Lynes, Robert Smithson, Reginald Marsh, George Segal, Tony Smith, Irving Penn, Marion Post Walcott, Cindy Sherman, George Tice, and, most famously, Alfred Stieglitz.

So, there is a serious element in the state, past the saltwater taffy, Miss America contests and Giants football in the Meadowlands. I’ve read work by all the authors, listened to music by all the singers and instrumentalists, either live or on recordings, and seen and often written about the visual artists. I hope that has also seeped in to the brainbox.

After all, maybe I don’t despise New Jersey like I used to, and perhaps I am not alone in having ambivalent feelings about the places that gave us birth and nurtured us. After all, Henry Thoreau complained about the torpor of Concord farmers and townspeople at a time when that village was also home to Emerson, Hawthorne and the Alcotts. Hmm. Might make for a good sonata.