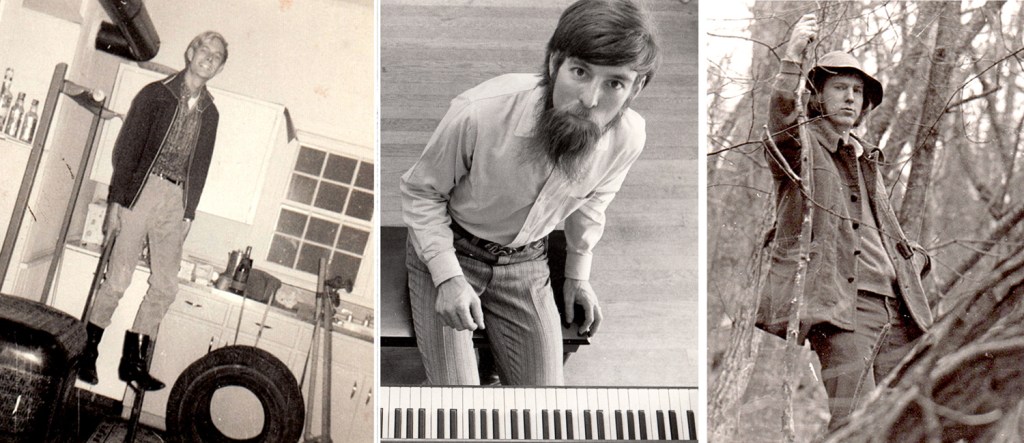

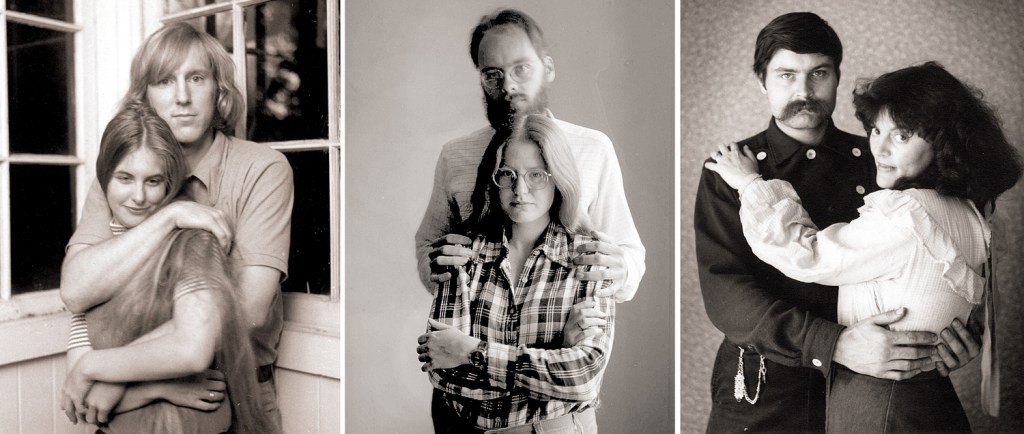

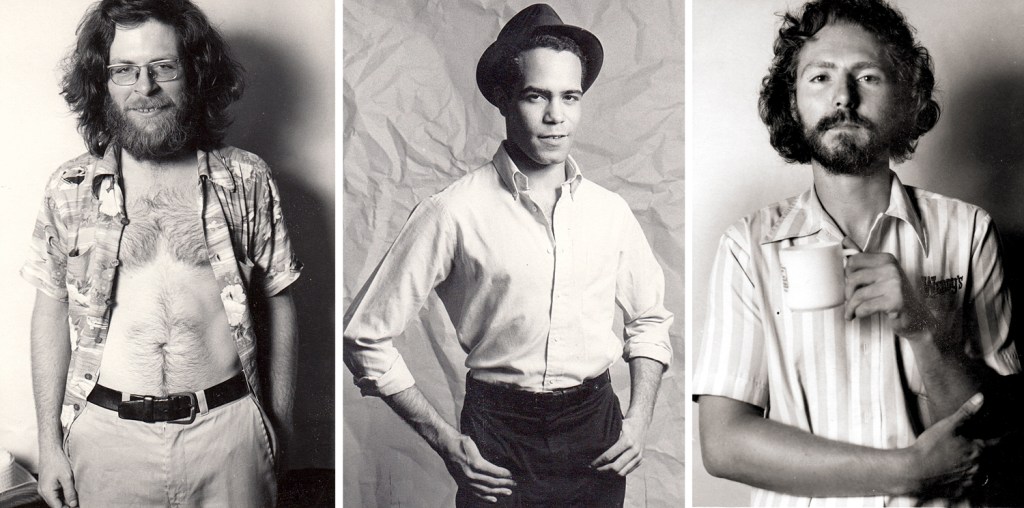

When I see photographs of myself in my 20s, I am deeply embarrassed. I seemed to be play-acting in some fictional version of the life I believed I was living, or wanted desperately to be living. I clearly thought I was ripe for la vie de Bohème.

I am probably not alone in this. From the onset of adolescence, most of us, I believe, are trying to figure out who we are, and believe — quite wrongly as it turns out — that we have some choice in this.

For me, as for quite a few in my generation, coming of age in the Eisenhower years, the banal middle-class life was something we wanted to escape. The world of art and artists — or poetry and poets — seemed so much more vital, so much more real.

It was in the air. Breathless, with Jean-Paul Belmondo, came out in 1960, when I was 12 years old. Jack Kerouac’s On the Road was released in 1957. In the same year, Alan Watts produced his Way of Zen. All of these things presented a way of life that seemed to this unformed New Jersey boy so much more real — so much more important — than buying annual new school clothes at the Paramus mall.

“What are you rebelling against?” “Whatya got?” Maynard G. Krebs.

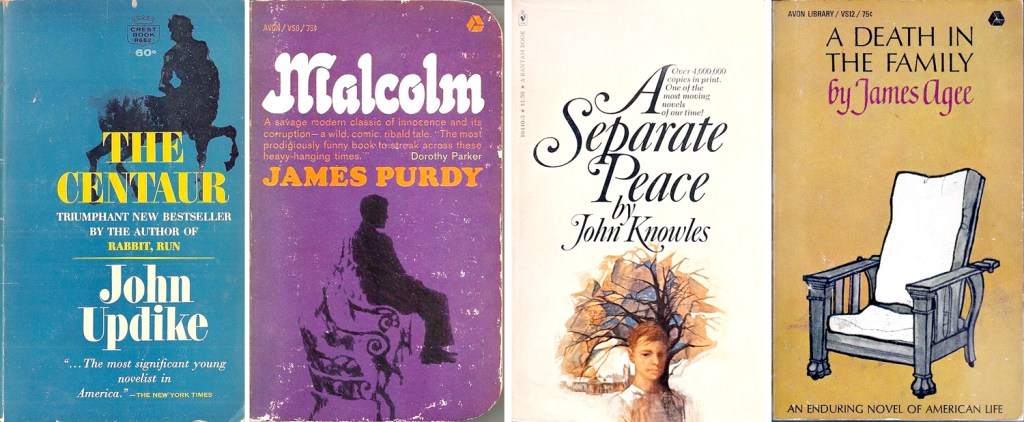

My parents were reasonably intelligent, but they were not college educated and they were not readers. I thought at the time they were intolerably boring. I read everything I could get my fingers on, including books that were way above my puny ability at that age to comprehend. I thought bourgeois respectability was the enemy, and in a fit of juvenile delinquency, I would stuff paperbacks from the book rack in the local drug store into my pocket and make off with them. I thought I was so daring, so rebellious. By real-life standards, it was pathetic; the real thugs in my town were Mafia kids and all the books I took were literary:

John Updike’s The Centaur; Malcolm by James Purdy; John Knowles’ A Separate Peace; The Sot-Weed Factor by John Barth; A Death in the Family by James Agee — you get the picture. As I look back on it now, I’m pretty sure that Everett, the pharmacist, knew what I was doing, but recognized that they were likely books that would never sell anyway in suburban New Jersey and that I would benefit from reading those books more than he would from keeping them dusty on his book rack.

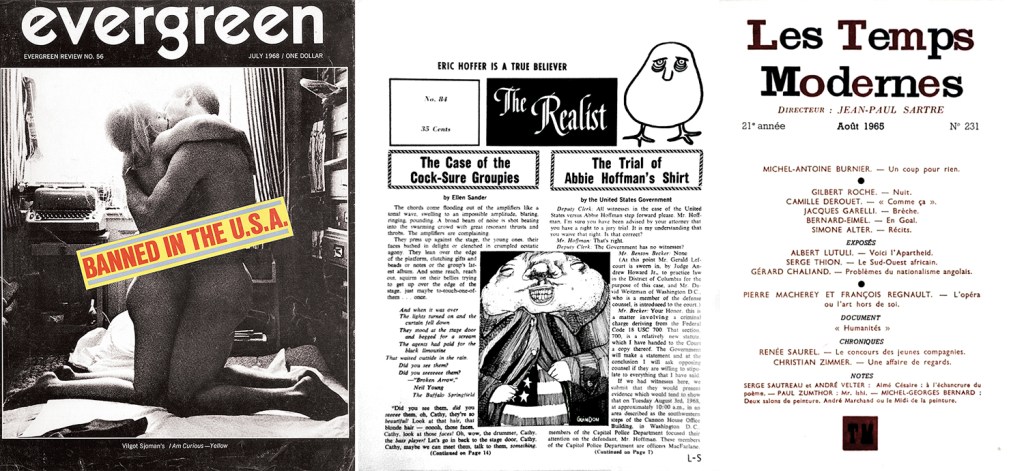

I bought a subscription to Evergreen Review and another to Paul Krassner’s The Realist. And just to go the extra length of high-school pretentiousness, I also got a subscription to Les Temps Moderne, although I knew no French. But, it was Jean-Paul Sartre’s magazine and I knew he was important. I was desperate to join the grown-up world of truly important things — not like the pep rallies and gym classes of high school.

The attraction of the bohemian life were all too apparent to me then, and all through my college years and into my 20s. It was a fantasy enriched by exposure to literature; actual bohemians were sparse on the ground in Bergen County. The tradition of poor scholars, thumbing their noses at conformity is long, and goes back at least to the Roman poet Catullus. I found a used copy of Francois Villon’s Testament and then, there was Goethe’s Faust and Puccini’s opera, La Bohème.

As I headed off to college, I imagined myself as one of those louche students, full of sex and alcohol, but also drunk on great books and music and art. Of course, there were others there who shared that vision and we became friends, like Rodolfo, Marcello, Shaunard, Colline, Mimi and Musetta.

Or so we imagined ourselves. I was filled with an exaggerated sense of art and literature, but lagged in classwork. I’m sure I read more than my curriculum required, but rather less of those texts assigned in class. After all, textbooks were dull and Dostoevsky was not.

We knew we were “special,” and that we would become, if not famous, at least important. My best friend and I self-published a slim volume of our poetry and titled the thing 1798, after the year Wordsworth and Coleridge published their Lyrical Ballads. Their poetry changed the climate for literature for the next hundred years; we expected ours would do the same. Being important was important to our yet unformed selves.

Rae, Aime and Alex

After graduation, with a first wife, I lived that sort of poverty, in a cheap rental apartment on the second floor of an old house, entered from stairs rising up the outside, and heated with a single kerosene stove in the living room and we ate from a book titled Dinner for Two on a Dollar a Day. I had a job paying minimum wage as a clerk in a camera store, and I found living on no money intoxicating. My first wife found it less so. A punctuation mark in the bio. Full stop.

Sandro and Mu; me and S; Cap’n Billy and Tiggy

Later, and with the succeeding unofficial wife, we lived in a duplex. I still worked in the camera store, and she was a cashier in a supermarket. We managed to save enough money to buy gear to hike the Appalachian Trail. We quit our jobs and took off for the woods. When we discovered that goal-oriented hiking (making the required miles per day to reach the next lean-to) was less glamorous than we thought, we gave up in northern Virginia and returned to Greensboro.

After that came some time on unemployment benefits and meeting up with fellow bohos in local bars, betting quarters on air hockey. Being poor was never a problem: It was exotic. We were still sleeping on a mattress on the floor, and having friends over for feasts, and at least once a year, with friends, renting a venue and holding a masked ball where we waltzed into the wee hours of the next day.

Ursus, Colin, and Spider in Seattle

But then, she left to get married and I was pole-axed. I hadn’t known. I gave up everything (well, except my books), and moved from North Carolina to Seattle, where I lived with my old chum, Ursus, who was then a bicycle messenger in the city. I was offered a spot in the coal bin in the basement, and lived more vie bohème on a mattress on the concrete floor. Being jobless gave me time for a lot of reading.

I eventually got a job at the zoo, and became crazy about a zookeeper I fell for, but depression wore me down.

And so, I moved back to the South and lived with my 1798 co-author and his wife. They gave me a room in their old farmhouse, with its only heat being a wood stove in the kitchen. I did the cooking and maintenance work while they went to work. A few daylong pick-up jobs and I earned a total of $900 for the entire year. It seemed sufficient. This was truly la vie de bohème.

My second official wife invited me to visit in the Blue Ridge and eventually, I moved in with her and her teenage daughter. Still no job, still poor as a midge and happy as a clam. But I was now over 30 years old and never had a real job. It was beginning to wear thin.

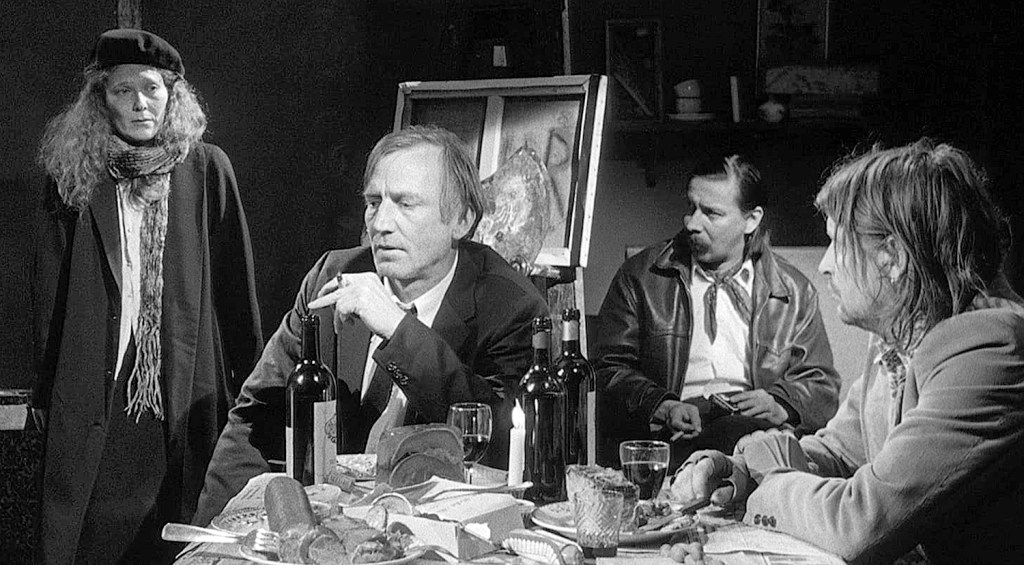

I mention all of this because I recently watched a 1992 film by Finnish moviemaker Aki Kaurismäki called La Vie de Bohème and based on the 1851 novel Scènes de la vie de bohème by French author Henri Murger, which, in turn, was the source for Puccini’s opera.

Henri Murger by Nadar, 1857

It is in many ways a brutal and heartbreaking film, mainly because, unlike the opera with its young heroes, flush with romantic enthusiasms, the movie shows us a more realistic vision of bohemians, now in their 40s, and looking pretty sad. It’s fine for 20-somethings to live their fantasies; but given greying hair, paunches and ratty clothes, at 40 living such a life seems like utter failure. Not only in career, but more important, as persons. They have not found who they really are, but have worn holes in the soles of who they try to be.

These are people who had grand ambitions when young. They were going to be writers, thinkers, painters. And they each now do piecework on commission for a few dollars and do their best to avoid creditors and landlords. When our writer falls in love with a worn-looking 43-year-old Mimi, he finds himself deported to his native Albania. When he sneaks back much later, he finds Mimi is dying. It’s all much as in the opera, only everyone is at least 20 years older.

But the love between Mimi and her man is so much more real and touching, because it is adults who need each other rather than youths living out some romantic fantasy, and Mimi’s death, in the hospital, is an actual death rather than a dramatic set-piece. Life has stomped on the youthful delusion.

For me, it was my second marriage, which lasted 35 years, until my wife’s death, that turned me into who I was rather than who I played at being. It can be a long process to something approaching reality.

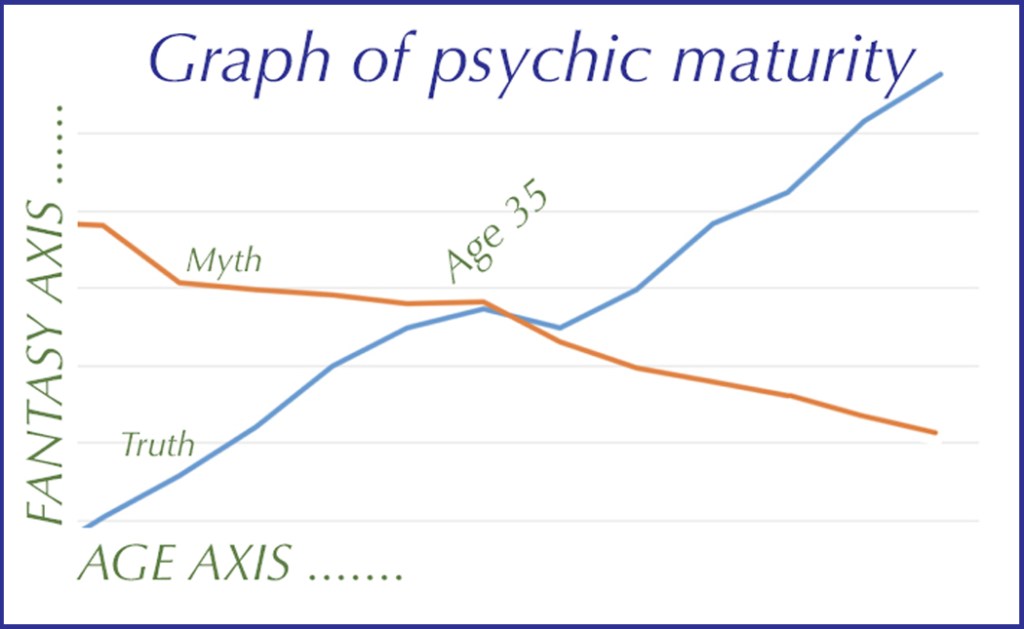

I don’t know if any of us can ever know who we really are, but we all know who we think we are. Most of us, as we get older, grow closer and closer to who we truly are; when we are young and full of ourselves, we live a mythologized sense of ourselves. A much more important sense of ourselves. We are going to change the world. In truth we are ordinary.

As one grows older, the graph plotting the importance of one’s internal sense of self, the mythology of autobiography begins to tail off, dropping down the chart, while the realization of who we truly are begins to climb, and there comes a point — for me, it was in my mid-30s — when the two lines cross. For some it marks the “mid-like crisis” and one can choose to attempt to grasp after the myth and buy a sportscar, or one recognizes that the actuality is more solid, more real, and more meaningful than the fantasy.

The young sense of self is a choice — a mask you wear or a role you play — and maybe you try to live up to it, but it is always a pose. The longer you hold on to it, the more you feel like an imposter. Who you are is not a choice: It is a given, and it can slowly reveal itself over time as you give up the pose. Maybe you give up the pose out of exhaustion, maybe out of a seeking of self-knowledge. Either way, it is why older people often feel so much more comfortable with themselves, so much less worried over what “others think.”

And for me, I have given up rebelling against the bourgeoisie. I have never joined in. I have too many books. But let them be who they are and let me be me.