In 2003, idiosyncratic filmmaker Guy Maddin released his most popular film (these things are relative), starring Isabella Rossellini and titled The Saddest Music in the World, about a contest held in Winnipeg, Canada, to find the most depressing music in the world. Each country sent its representative to win the $25,000 prize put up by beer baroness Helen Port-Huntley (played by Rossellini with artificial glass legs filled with beer). The middle portion of the film features performances by many of the contestants. But the film misses the serious winner in its hijinx of weirdness.

Because the truly saddest music in the world is, hands down, Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto, music that can only rip your heart out and leave you prostrate with Weltschmerz. For it is not simple personal grief that Elgar wrote into the music, but the sense of the core sadness of life and the failure, of the world he knew, to survive the First World War.

Elgar was born in 1857, a decade before the deaths of Rossini and Berlioz, and became widely regarded as the first great English composer since Henry Purcell (1659-1695). He lived to see the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany — a long life full of incident and occasion.

But until the age of about 40, he was primarily a choral composer and a maker of musical trifles — salon music such as the ever-popular Salut d’Amour that is still an occasional encore piece. Still, that music gave him the reputation as the most important composer in England, second only to Sir Arthur Sullivan. He became an itinerant musician, sometimes teacher, and, at 29, married his student, Caroline Alice Roberts, whom he remained married to for 31 years. Because Elgar was Roman Catholic and from a working-class background, Alice’s upper-class parents disapproved and disinherited her. But their marriage was successful and productive. After her death in 1920, Elgar wrote no more music of significance. He died in 1934. (Despite his Catholicism, he told his doctor at the end that he had no belief in an afterlife. “I believe there is nothing but complete oblivion.”)

Elgar always wanted to write more significant music and then, in 1899, at the age of 42, he made his bid for musical importance with a set of variations for orchestra. The “Enigma” Variations remain his most popular and most performed composition, a brilliant set of 14 variations, each of which was meant as a portrait of one of his friends.

The following year, he premiered his masterpiece oratorio, The Dream of Gerontius, setting the poetry of Alfred Cardinal Newman, in a rich, late-Romantic orchestration rivaling the style of Richard Strauss. Its Catholic doctrine (a soul’s journey to Purgatory) may have prevented it becoming as popular as it might, but it is lush and gorgeous.

In the years up to the First World War, Elgar wrote the bulk of what he is now famous for. His Introduction and Allegro for String Quartet and Orchestra (1904); First Symphony (1908); Violin Concerto (1910); Second Symphony (1911); Falstaff (1913). He was knighted in 1904 and a shower of awards and honors fell upon him after that.

He is usually thought of as an Edwardian composer, and identified with those years of English jingoism and colonialism. And it is hard to shake that notion when you hear, once again, his Pomp and Circumstance marches. But he really was no Colonel Blimp. And the Great War defeated him, knocked him down and left him deflated. The world order he grew up in was ripped apart and left in tatters. As British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey remarked in 1914, “The lamps are going out all over Europe and I do not think we will see them lit again in our lifetime.”

All the optimism and faith in progress that marked late Victorianism and the early years of the century were gone. It can be hard for us to imagine now, after the even-worse cataclysm of WWII and gulags and the Cultural Revolution, just how monumental and devastating the Great War was. It was to those who lived through it, as if the world were ending. Twenty million deaths, the overturning of governments, the shift of world power from the Old World to the New.

All this, Elgar felt. The concerto was composed during the summer of 1919 at Elgar’s cottage in Sussex, where during previous years he had heard the sound of the artillery at night rumbling across the Channel from France. And at the end of the war, he summed up his despair in the Cello Concerto in E-minor, his last great orchestral work. After it, he could never work up the enthusiasm to write more.

The work is intensely beautiful, but also profoundly sad. All the sense of loss is bound up in it. And while Elgar’s music had been regularly applauded wildly on premiere, sometimes encored twice. The Cello Concerto was a failure when it was first played at Queen’s Hall, London, in 1919, partly to being under-rehearsed and badly played, but, mostly because of its somber tone.

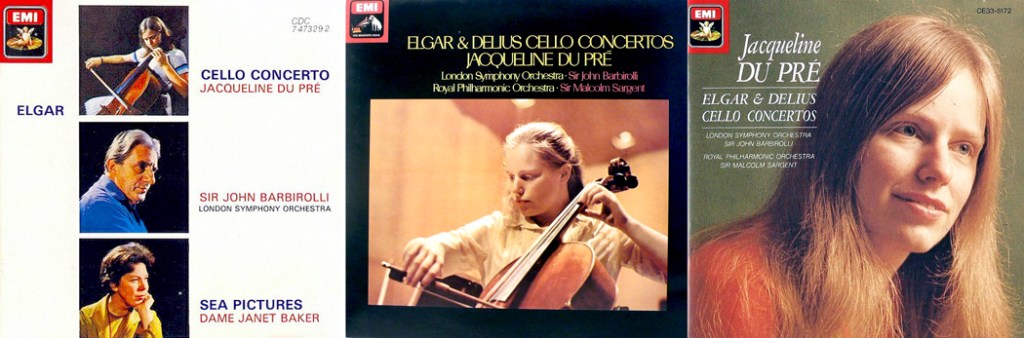

In fact, it languished, rarely programed until a 1965 recording by 20-year-old Jacqueline du Pré with John Barbirolli and the London Symphony — a recording that has never been out of print since its first release. Du Pré’s performance was so emotionally present and direct, so attuned to the music, that it has been the benchmark performance ever since. And it reawakened interest in the concerto, so that now almost any cellist worth his or her salt, has it in their repertoire.

After the concerto, Elgar wrote three great pieces of chamber music: his Violin Sonata, a string quartet and a piano quintet, all written by 1920. After that, only trifles — reworkings of old music and orchestrations of the music of other composers. He found an interest in the new technology of recording and made a groundbreaking series of discs of his own music, recordings still available, now on CD.

But the war and Alice’s death seem to have taken the drive out of him. Elgar died Feb. 23, 1934 at the age of 76 and was buried next to his wife at St Wulstan’s Roman Catholic Church in Little Malvern, in the English Midlands.

Elgar was without doubt a great composer, but, as critic David Hurwitz has said, “a great composer but not a necessary one.” Elgar himself knew he was a bit of an anachronism, a late-Romantic composer in a century headed toward Modernism. By the time of his Cello Concerto, Stravinsky had already written his Sacre du Printemps and Schoenberg his Pierrot Lunaire. Some of the loss and longing of Elgar’s concerto is surely his sense of being adrift in the Luft von anderem Planeten — the air from another planet, that Schoenberg announced.

The history of music would not have been any different if Elgar had never written — something that cannot be said of Stravinsky or Schoenberg. Yet, you cannot listen to Elgar’s best music — the two concertos, Gerontius or the “Enigma” Variations — and not sense in him a power and emotional sweep that lifts him to the first rank. In that sense, his music is indeed necessary.

__________________________________

“There is music in the air, music all around us, the world is full of it and you simply take as much as you require.”

—Edward Elgar, 1896

__________________________________

There are certain pieces of music that everyone knows, whether they know it or not. They are simply in the air. They are heard not just in concert halls, but in film, TV commercials, pop songs — and at every high school graduation ceremony in the English-speaking world. Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 is the graduation music — or at least the “trio” portion of it.

It is the portion of the march that was re-written, by Elgar himself, as the popular British patriotic song, Land of Hope and Glory, now sung by the home crowd with soccer victories, and as the audience stands and sings along at the final Proms concert of the season in London. And as the new high school graduates line up to receive their diplomas in school auditoriums everywhere.

The practice began at Yale University in 1905 when Elgar was awarded an honorary degree for which the composer traveled to the U.S. It was decided to surprise him by playing his own music for the event, and they played Pomp and Circumstance. The practice caught on elsewhere, and is now ubiquitous as “The Graduation March.”

And so, generations of Americans know the music well, without knowing, necessarily, what the music is they are hearing. It’s just “the Graduation March” of unknown provenance, as if it had just always existed.

There are other such tunes, well known but genericized. There is Wagner’s Wedding March from Lohengrin — “Here comes the bride, all dressed in white…” — probably not recognized as from an opera. Or Mendelssohn’s Wedding March from his incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Mendelssohn has ceased to own it: It is truly public domain.

For many Americans, our first exposure to classical music came from Warner Brothers cartoons, and Bugs Bunny conducting Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in a parody of Leopold Stokowski. Or Elmer Fudd singing “Kill the Wabbit. Kill the Wabbit” to the tune of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries.

That Hungarian Rhapsody got heavy use from animated films. Not only Bugs conducting, but Bugs playing the piano, and others, from Tom and Jerry to Woody the Woodpecker also took their turns with Liszt.

Or maybe watching the Lone Ranger on TV and hearing the William Tell Overture. Or television reruns of the old Buster Crabbe serials of Flash Gordon, with Liszt’s Les Preludes as its persistent soundtrack.

Some scores have been used scores of times in movies. Samuel Barber’s heartbreaking Adagio for Strings has shown up in at least 32 films and TV shows, including: The Elephant Man (1980); El Norte (1983); Platoon (1986); Lorenzo’s Oil (1991); The Scarlet Letter (1995); Amelie (2001); S1mOne (2002); and three episodes of The Simpsons.

Popular songs have stolen classical tunes. The Minuet in G from Bach’s “Anna Magdelena Bach Notebook” became The Lover’s Concerto, recorded in 1965 by the Detroit girl group, The Toys. The Big Tune from Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto became Full Moon and Empty Arms, sung by Frank Sinatra in 1945. Tony Martin turned Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto into Tonight We Love. I’m Always Chasing Rainbows was originally Chopin. The Negro Spiritual Goin’ Home was actually taken from Antonin Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony. Stranger in Paradise is one of Borodin’s Polovetsian Dances, and so is Baubles, Bangles and Beads.

The list goes on: Tin Pan Alley was full of burglars. Hot Diggity, Dog Ziggity was based on Chabrier’s España; Catch a Falling Star (and Put it in Your Pocket) was the Academic Festival Overture by Brahms; Love of My Life, by Dave Matthews and Carlos Santana is from Brahms’ Third Symphony. You can find hundreds of these “steals” on Wikipedia.

I asked my brother, Craig, for any examples he might think of, and he sent back this barrage:

“So, what’s Classical? It’s probably a close cousin to porn — I know it when I hear it.

“There are Classical music quotes all over TV and movies, and my Classical education was jump-started by Bugs Bunny and his friends, and a little later by Fantasia and Silly Symphonies. A really surprising amount of music got introduced to me in cartoons.

“But that is a different thing from pieces of music being a part of our lives, like ‘Here comes the bride,’ and ‘Pomp and circumcision’ at every graduation ever. WW2’s theme song was Beethoven’s 5th. The military loves them some Sousa marches. Everybody knows the more popular Ave Maria. Everyone knows some snippet of Figaro. In fact there are a ton of little pieces of operas than we are all a little familiar with, even if we can’t name the opera or composer. If we played “Name that Carmen” most people would say, oh, yeah, I know that, but couldn’t name the source. There are a whole poop load of snippets we’ve all heard without knowing where the came from. (Thanks, Bugs.)

“Toccata and Fugue, a passel of Puccini, Bolero, (Thanks, Bo Derek), The Blue Danube, the Saber Dance (Thanks Bugs?), the Ritual Fire Dance (Thanks Ed Sullivan and the plate spinners), Für Elise, Chopsticks (Thanks, Tom Hanks), the Ode to Joy, the thoroughly quotable Swan Lake, Ride of the Valkyries (Thanks Robert Duvall), Voices of Spring, O Fortuna from Carmina Burana (Thanks Madison Avenue), Funeral March of the Marionettes, (Thanks, Hitch), Adagio for Strings, The Skater’s Waltz, Minuet in G, the Olympics theme, “Moonlight” Sonata, anything from the Nutcracker, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (Thanks, Uncle Walt).

“This is a pretty pointless list, because it is kind of endless. And I might well be making a baseless assumption about American’s familiarity with these things, just like I am thinking that American’s familiarity with these pieces of music is inversely proportional with the number of guns they own.

“Pachelbel’s Canon in D (which is much more memorable than his Canons A through C), Flight of the Bumblebee (the theme music for The Green Hornet, which is I’m sure too obscure a reference to be very useful), the 1812 Overture (Thanks, Boston Pops and Quaker Puffed Rice), A Clockwork Orange made the point pretty directly about Classical music being embedded in the culture, with street thug Alex loving Beethoven deeply. Strauss’ Zarathustra in 2001 (Thanks, Stanley), Flash Gordon used Liszt’s Les Preludes (which I have had playing nonstop in my head since I thought of it). Lugosi’s Dracula used Swan Lake (which always strikes me as a real cheapskate move to do).

“The Lone Ranger music isn’t even a decent trivia question anymore because everyone knows the musical source.

“So I’m just throwing up blunderbuss answers to ‘what’s embedded in our culture.’ So I’m gonna stop here. I hope there’s something you can use.”

And I’m sure, you, dear reader, can think of many more.