I want to acknowledge a debt. It comes as a bit of an ugly confession. And it comes wrenchingly from my throat: I write a great deal about books and poetry. I spout Roman history a little too glibly and am apt to swoon glowingly about Homer’s Iliad.

But I must acknowledge that the high tone of fine art and literature is only a patina. I have been most hewn and polished not by literary sources, but by television. It is the same for most people under the age of 65.

Television is not often enough considered when we talk about intellectual development; it actually hurts to put the words ”intellectual” and ”television” in the same sentence — and I just did it twice. I’m a masochist.

But it is true. My first introduction to classical music was on the Bugs Bunny cartoons I watched on the box. First introduction to jazz from the added soundtrack to the silent Terrytoons I saw on Junior Frolics, an afternoon kiddie show on New Jersey’s Channel 13, hosted by “Uncle” Fred Sayles. Those silent-era animations, with their added jazz scores influenced my youth in a way that Aeschylus would never be able to.

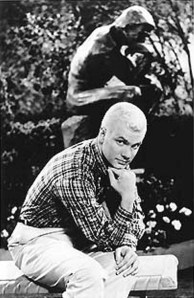

My first theater came in the form of sitcoms; first sculpture was the Rodin Thinker that Dobie Gillis sat under to question why he could never make time with Thalia Menninger.

Oh, there were a few ”highbrow” things on the tube: Sometimes we watched Omnibus with Alistair Cook or the Young People’s Concerts with Leonard Bernstein.

Nevertheless, the effect of such educational shows was as a single tiny green pea to the overwhelming harvest of corn that poured out of the box.

Bonanza, Ed Sullivan, Jackie Gleason, Ozzie and Harriet, Dave Garroway’s meaty palm held forward to the screen as he intoned the word, ”Peace.”

I learned about animals from Ivan Sanderson and, later, Marlin Perkins. I learned about Eastern Europe from Boris Badinov. It all twirled around in a great pop-culture spin cycle.

It’s frightening to think how much American history was gathered from watching Hugh O’Brian as Wyatt Earp or Guy Madison as Wild Bill Hickok.

It is all still there, like petroleum under the covering layers of rock. If I dig deep enough, the Tacitus recedes and Sky King comes back to the fore.

But it isn’t mere nostalgia that I mean to invoke, but rather a change that has come about as television has come of age.

What distinguishes the generation that came after mine — those called ”X” to my ”boomer” — is the quotes that have now been put around everything that appears on the screen.

Television was new to us. We approached it naively. What we saw on its glowing front we took to be an image of the real world. Those that came after us were enormously more sophisticated about what they saw. Television was for them clearly an ironic ”parallel universe,” which they somehow lived in, used for their cultural reference point, but never took seriously.

The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet was not exactly the world I inhabited, but it bore a close enough resemblance to it that I could read it as ”real.” Ozzie really was married to Harriet.

By the time The Brady Bunch came on, it so deviated from the reality of its viewers that the only way to enjoy it was as an in-joke.

My generation learned about World War II from Victory at Sea; the following generation learned from Hogan’s Heroes.

There are many a plus and beaucoup minuses to both sides of the generational equation. It is usually better to be sophisticated than naive. I’m mortified that I ever thought that Gene Autry really was a cowboy.

But the downside for the later generation is the disconnect they make between life and art. For them, culture is a web of references they get, the way you either get or don’t get Stephen Colbert. If you suggest to them that art might somehow mirror their daily existence and confront the questions that arise outside the TV world, they look at you like you just suggested Larry the Cable Guy should be the next James Bond.

If we have all become much more knowing about the apparatus of media, we are also in danger of drowning in that world in a kind of cultural schizophrenia, and forgetting that the world that counts is found outside prime time.