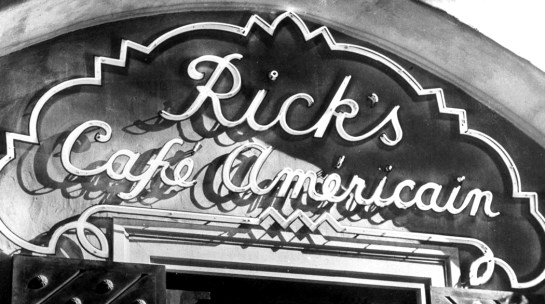

Casablanca is one of the best loved films ever to come out of the Hollywood studio machine, but it is hardly the story that makes it so. After all, the basic plot is “boy loses girl,” “boy finds girl” and “boy loses girl again.” A pretty thin thread to hang an epic on, even if the boy and girl are Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman.

And the movie’s success is especially surprising considering what a mess its making was, well-documented in several books: many rewrites; a team of script doctors; and an ending that wasn’t known or decided upon until the last moment. And that is beside the fact that most of the plot details were simply not believable, or had no basis in historical fact. In other words, pure succotash.

The love story may have been enough to make Casablanca a successful run-of-the-mill studio release in 1942 — after all, Warner Brothers churned them out by the bucketload — but the film has a secret ingredient that lifts it up to a classic. And sometimes, they barely spoke English.

The love story may be the mortar that holds the story together, but it is the hundred extras, with their vivid vignettes, that are the bricks that form the substance and power of the movie. And those bit parts, most played by actual refugees from the war and from the Nazis, breathe actual life into the film.

Each goes by so fast, you may not notice how many of them there are. Between each scene that advances the plot, there are interlarded brief glimpses into the lives of those made stateless, seeking a way to escape the horrors of war and fascism. The complete cast list on IMDb of those uncredited actors is a hundred names long, and most of those were actual refugees, making scant living in Hollywood.

In fact, of the credited actors at the top of the cast, only three were born in America, and of the three primary characters, only Bogart, who was born in New York City in 1899. Down the roster, you have Dooley Wilson, born in Texas in 1886; and Joy Page, who also happened to be the step-daughter of Warner studio head, Jack Warner (she played the Bulgarian refugee, Annina, who almost gives herself to police chief Louis in order to save her husband).

Let’s go down the list. Not all of them fled Nazis, but all were caught up in the turmoil in Europe.

Ingrid Bergman (Ilse Lund) — Born in Stockholm in 1915 to a German mother, she spent summers as a child in Germany. In 1938, she made a film for the German movie conglomerate, UFA. But she said, “I saw very quickly that if you were anybody at all in films, you had to be a member of the Nazi party.” She never worked in Germany again.

Paul Henreid (Victor Laszlo) — Born in 1908 as Georg Julius Freiherr von Hernreid, Ritter von Wasel-Waldingau in Trieste, which at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father was born a Jew, but converted to Catholicism in 1904 to avoid the anti-Semitism in Austria. Henreid was nevertheless persecuted as Jew by the Nazis after the Anschluss, and his application to work in the German film industry was rejected personally by Joseph Goebbels.

When he helped a Jewish comedian escape from Germany in 1938, he was declared an “official enemy of the Third Reich” and his assets were confiscated. He then escaped to England and then to Hollywood in 1940.

Conrad Veidt (Major Heinrich Strasser) — Veidt, born in 1893 in Berlin, had a long, successful career in German silent films (famously playing Cesare the somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in 1920), but when the Nazis came to power, like all German actors, he was required to fill out a “racial questionnaire” and declared himself a Jew, although he wasn’t, but his wife, Ilona Prager, was. He smuggled his in-laws from Austria to neutral Switzerland, and even helped his former wife, Radke, and their daughter escape. He also got out, first moving, to England in 1939 and to the US in 1941.

A staunch anti-Nazi, he wound up playing many Nazis in American movies, although his contract stipulated that he would only do so if they were villains. Veidt said it was ironic that he was praised for playing “the kind of character who had force him to leave his homeland.”

“You know, Rick, I have many a friend in Casablanca, but somehow, just because you despise me, you are the only one I trust.”

Peter Lorre (Signor Ugarte) — Hungarian Lorre was born Laszlo Lowenstein in what is now part of Slovakia in 1904 (many borders have changed). He had been a very successful actor in German films — playing child murderer Hans Beckert in 1931 in Fritz Lang’s M, a film the Nazis later condemned and they even used a clip of Lorre in the propaganda film The Eternal Jew, implying that Beckert was typical of Jews.

Lorre’s parents were German-speaking Jews (his mother died in 1908). The actor left for Paris in 1933, later moving first to London and in 1935, to Hollywood.

Claude Rains (Captain Renault) was born in London in 1889 and moved to the US in 1912; and Sydney Greenstreet (Signor Ferrari) was born in Kent, England in 1879, the son of a tanner, and began working for Warner Brothers in 1941.

So, the rise of Hitler and Nazism affected the majority of the above-the-line cast of Casablanca, but it is the character actors and the extras where the story really plays out. Most of these were not even part of the source material for the movie.

In 1940, writers Murray Burnett and Joan Alison wrote an anti-Nazi play called Everybody Comes to Rick’s, about the cafe owner in Morocco helping a Czech resistance fighter escape, with “Lois,” the woman Rick, the cafe owner, is in love with. That play, unproduced, was bought by Warner Brothers and handed over to studio screenwriters, who buffed it up, rewrote dialog and dithered over its ending. First Casey Robinson (writer on Captain Blood) worked over the play, beefing up the romantic plot of Rick and Ilse; then Howard Koch (writer on The Sea Hawk), worked on the politics; and twin-brother writers, Julius and Philip Epstein, script doctors punched up dialog and restructured the plot (together they had brightened up the banter in The Man Who Came to Dinner).

Koch and the Epsteins won the Oscar as Casablanca’s screenwriters; Burnett, Alison, and Robinson were nowhere to be mentioned.

The original play was compelling enough finally to be successfully produced in London in 1991, and it provided what Koch called “the spine” of the movie, but it is the dozens of brief details that make so much of the film memorable, beginning near the opening, when a middle class English couple (Gerald Oliver Smith and Norma Varden, both British) are interrupted by a thin, nervous pickpocket (Curt Bois).

“I beg of you, Monsieur, watch yourself. Be on guard. This place is full of vultures, vultures everywhere, everywhere.” A moment later, the Englishman says, “Oh, how silly of me. I’ve left my wallet at the hotel.”

The scene takes only seconds on screen, but sets the tone for irony, cynicism and dark comedy. Bois was a Jew born in Berlin, who escaped Germany in 1934, after the rise of Hitler.

(To understand what the Epsteins gave the movie, the original script has Bois saying only, “M’sieur, I beg of you, watch yourself. Take care. Be on guard.”)

Such slight moments, throughout the movie, keep every second alive and vivid. And most play out with actors who have fled Europe. Such as:

Melie Chang, Torben Meyer and Trude Berliner

Trude Berliner — born 1903 in Berlin. Jewish. Left Europe in 1933 when Nazis came to power. In the film, she portrayed a woman playing baccarat with a Dutch banker, played by Torben Meyer, Danish, born 1884, who came to the US in 1927. In one scene, she asks Carl, the waiter, “Will you ask Rick if he will have a drink with us?” “Madame, he never drinks with customers. Never. I have never seen it.” When Meyer say he runs “the second largest banking house in Amsterdam” “Second largest?” says Carl. “That wouldn’t impress Rick. The leading banker in Amsterdam is now the pastry chef in our kitchen.”

Then, there’s the sweet old couple who are learning English for their trip to America. “Liebchen, sweetheart, what watch?” “Ten watch.” “Such much?” They are:

Ilka Grünig — Jewish actress from Vienna, born 1876. Left Germany in 1938 after the Nazis came to power. and:

Ludwig Stössel — Born 1883 in Leika, Hungary (now Lockenhaus, Austria. I mentioned borders changed a lot) After the Anschluss, Stössell was imprisoned several times but was able to escape Vienna and get to Paris, and then to London.

And the woman who “has to sell her diamonds,” Lotte Palfi Andor, born 1903 in Bochum, Germany, a Jewish stage actress who had to flee in 1934 with her husband, Victor Palfi, after the Nazis came to power. Offered a small amount for her jewels, she asks, “But can’t you make it just a little, more? Please?” The buyer says, “Sorry, but diamonds are a drug on the market. Everybody sells diamonds. There are diamonds everywhere.”

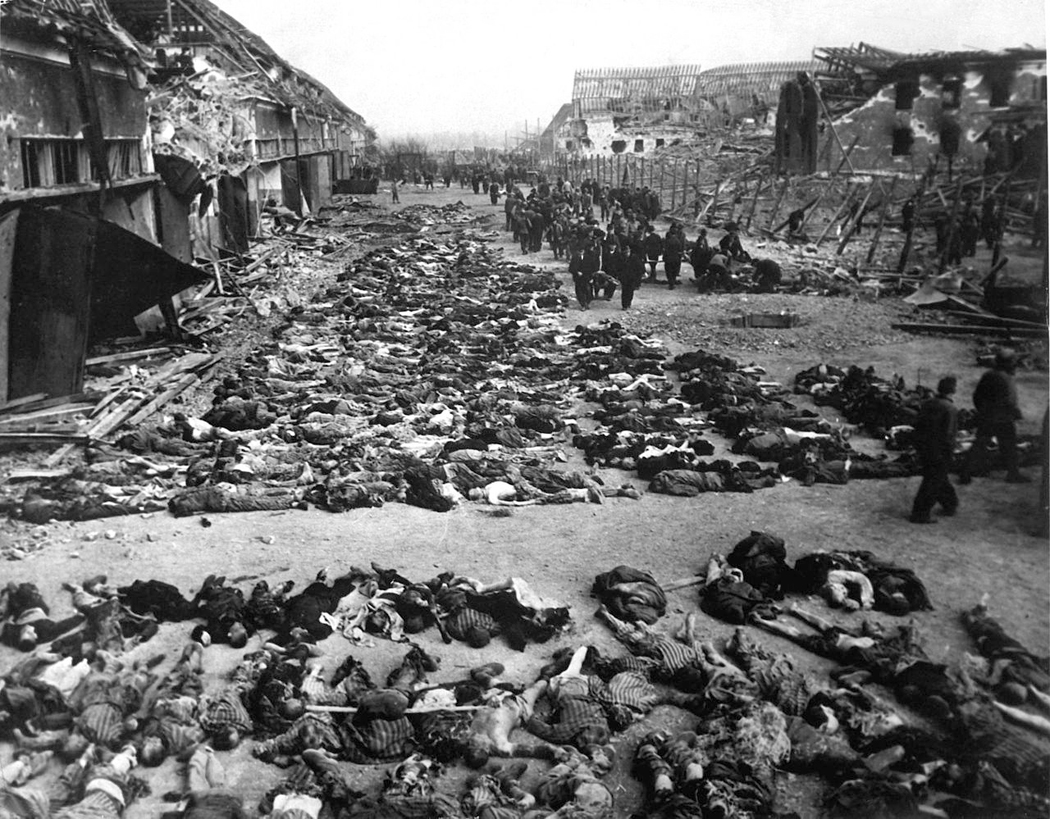

Marcel Dalio, born in Paris in 1899 as Marcel Benoir Blauschild, had featured in two of the greatest films ever made, Rules of the Game and The Grand Illusion, for Jean Renoir. He was born to Romanian-Jewish immigrants and left Paris in 1940, ahead of the invading German army, reached Lisbon, went to Chile, to Mexico, to Canada and finally to Hollywood, where he found small roles, such as Emil the Croupier in Casablanca. In occupied France, his face was used on posters as a representative of “a typical Jew.” All other members of Dalio’s family died in Nazi concentration camps.

After the Bulgarian youth wins twice at the roulette, betting on the same number, Rick asks Emil, “How we doing tonight.” The surprised croupier answers, “Well, a couple of thousand less than I thought there would be.”

The youth was played by Helmut Dantine, born 1918 in Vienna. When he was 19, after the Anschluss, he was rounded up with hundreds of opponents of the Third Reich and sent to a Nazi concentration camp. He parents bought his release and sent him to California, where he made a living playing Nazis in various movies.

Madeleine Lebeau played Bogart’s discarded girlfriend, Yvonne. “Where were you last night?” she asks Rick. “That’s so long ago, I don’t remember.” “Will I see you tonight?” “I never make plans that far ahead.”

Lebeau married Marcel Dalio in 1939 and the both had to flee Paris ahead of the German advance. Her best moment in the movie is when the French sing La Marseillaise against the Germans singing Die Wacht am Rhein. Many of the actors in the scene were real-life refugees from Europe, and Lebeau ends with “Vive la France! Vive la democratie!” with tears in her eyes. “They’re not tears of glycerin shed by an actress,” recalled Leslie Epstein, son of the screenwriter. “The tears in her eyes are real.” Another actor noticed everyone was crying: “I suddenly realized they were all real refugees.”

Richard Ryen was born Richard Anton Robert Felix Revy in Hungary (now Croatia) in 1885 and worked as an actor in Germany and became a well-respected stage director at the Munich Kammerspiele (Munich Chamber Theater). He was expelled by the Nazis and emigrated to Hollywood, where he made a living playing Nazis. In Casablanca, he follows behind Major Strasser like a puppydog.

Louis V. Arco was born in 1899 in Baden bei Wien, in Austria Hungary as Lutz Altschul. He escaped to America after the Anschluss. Near the beginning of Casablanca, he is looking very depressed and has one line: “Waiting, waiting, waiting. …I’ll never get out of here. …I’ll die in Casablanca.”

Wolfgang Zilzer was a special case. He was born in 1901 in Cincinnati, Ohio to touring German film actor, Max Zilzer and moved with his family back to Germany in 1905. The young Zilzer worked for UFA before the war, but after Hitler’s rise to power, he fled to France. He returned briefly to Germany in 1935, but then applied for a visa to emigrate to the US, only then realizing he was already a US citizen. In Hollywood, he made several anti-Nazi pictures with Ernst Lubitsch, but used a pseudonym to protect his father, still in Germany. Zilzer married German Jewish actress Lotte Palfi. In Casablanca, Zilzer played a man without a passport who is shot by the police at the beginning of the film.

Probably the best known of the emigres was S.Z. Sakall, born in 1883 in Budapest to a Jewish family, and known by everyone as Cuddles. He played the head waiter Carl. “Carl, see that Major Strasser gets a good table, one close to the ladies.” “I have already given him the best, knowing he is German and would take it anyway.”

Sakall was a familiar character actor in Hollywood in the ’40s and ’50s appearing in scores of films as kindly European uncles and befuddled shopkeepers. He escaped the Nazis in 1940 and moved to Hollywood. Sakall’s three sisters and his wife’s brother and sister all died in Nazi concentration camps.

Hans Heinrich von Twarkowski was born in 1898 in Stettin, Pomerania, in Germany (now Szczecin, Poland). He escaped Germany as a homosexual, threatened by the Nazis, and like so many refugees, ended ironically playing Nazis in the movies.

Not all the actors escaped the Nazis. Some fled Stalin’s Soviet Union, such as Leonid Kinskey, born 1903 in St. Petersburg. He fled first to Germany in 1921 and then came to the U.S. in 1924. He played the bartender Sascha in Casablanca. “Sascha, she’s had enough.” “I love you, but he pays me.”

Gregory Gaye was also born in St. Petersburg, in 1900, and had been a cadet in the Imperial Russian navy. He fled the USSR in 1923, and worked as an actor in Europe and Asia before moving America. In Casablanca, he played an official in Hitler’s Reichsbank and tries to enter the back-room casino in Rick’s cafe, but is stopped by Abdul (Dan Seymour). He tells Rick, “I have been in every gambling room between Honolulu and Berlin, and if you think I’m going to be kept out of a saloon like this, you’re very much mistaken.” Rick tells him, “Your cash is good at the bar.” He responds, “What? Do you know who I am?” To which Rick replies, “I do, you’re lucky the bar is open to you.” Gaye angrily responds, “This is outrageous! I shall report it to the Angriff” and storms away. (The Angriff was the official Nazi propaganda newspaper.)

They weren’t all Germans or Jews, but some 34 different nationalities were found in the cast and crew of Casablanca, including Hungarian-born director Michael Curtiz, who worked as a film director for UFA in Germany before moving to America in 1926; and English-born film editor Owen Marks who came to the US in 1928 (and won an Oscar for Casablanca); and Carl Jules Weyl, born in Stuttgart, German and was the art director; and composer Max Steiner, born in Vienna and naturalized as an American citizen in 1920.

John Qualen, who played Berger the jewelry-selling Norwegian resistance member was born in Vancouver; Frank Puglia, the Moroccan rug merchant was born in Sicily; Nino Bellini, who played a gendarme, was from Venice, Italy.

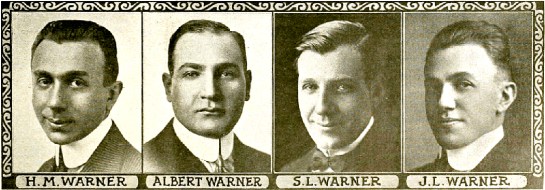

And, of course, the studio heads, the Warner brothers, Harry, Albert, Sam and Jack, born in Poland and victims of vicious anti-Semitism there, who came basically penniless to the US and built up one of the largest movie studios, and notably the first to make films about the dangers of Nazism, which, in the 1930s was not a popular position.

Charles Lindbergh at America First Rally in Fort Wayne, Indiana

An overwhelming majority of Americans opposed the resettling of Jewish refugees; hundreds of thousands of people were turned away in the 1930s. As late as 1939, 20,000 American Nazis held a rally in Madison Square Garden in New York. And America aviation hero Charles Lindbergh headed the isolationist America First movement. Father Charles Coughlin and industrialist Henry Ford preached rabid anti-Semitism and praised Adolf Hitler.

In 1932, Joseph Breen, soon to become head of the Production Code Administration (PCA), the censorship arm of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, called Jews “the scum of the scum of the earth” and “dirty lice.” Breen would soon be charged with enforcing a ban on anti-Nazi films in Hollywood between 1934 and 1941, at the behest of Joseph Goebbels, by way of the Nazi consul in Los Angeles, Georg Gyssling.

“Confessions of a Nazi Spy,” 1939 Warner Bros.

While most of the studio heads complied with the ban, which also strongly discouraged the production of films about Jewish subjects or featuring Jewish actors, the Warner brothers did their best to fight back. The studio ended all business relations with Germany in 1934, and even a year earlier had made fun of Hitler as an incompetent ruler in an animated film. The Warners were the only studio heads to support the 1936-created Anti-Nazi League, and most notably, made the 1939 film, Confessions of a Nazi Spy, based on a real-life espionage case and starring Edward G. Robinson (born Emanuel Goldenberg in 1893 to a Yiddish-speaking Jewish family in Bucharest, Romania).

The film defied the PCA ban on films attacking foreign leaders, but Jack Warner said, “It is time America woke up to the fact that Nazi spies are operating within our borders. Our picture will tell the truth — all of it.” Confessions predated the later Chaplin film, The Great Dictator and the Three Stooges short, You Nazty Spy!, both released in 1940.

So, Casablanca has a studio history behind it.

Later, in the 1950s, when McCarthyism threatened America with its own brand of fascism, many Hollywood notables were called to inform on their colleagues. The Epstein twins were reported to the House Un-American Activities Committee and were quizzed if they had ever been members of a “subversive organization,” and they answered, “Yes. Warner Brothers.”

Envoi

Thanks to its many screenwriters, and especially the Epstein brothers, Casablanca is famously quotable from first to last. We all have our favorites. The American Film Institute, which publishes lists of greatest films and greatest performances, put out a list of the “Top 100 Quotes from American Cinema” and Casablanca takes six of the spots, twice as many as second place — a tie between Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz.

No. 5 “Here’s looking at you, kid.”

No. 20 “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

No. 28 “Play it, Sam. Play As Time Goes By.”

No. 32 “Round up the usual suspects.”

No. 43 “We’ll always have Paris.”

No. 67 “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”