A Tale of Two Books

I’m wearing a virtual foam collar around my brain stem, suffering from a kind of whiplash, having finished one book, so devastating and depressing, and having begun another so invigorating and life-affirming — really, brain-affirming — that my poor psyche feels like Faye Dunaway in Chinatown, slapped back and forth by Jack Nicholson.

I recommend both.

The first is a recounting of the inhumanity humanity deals to itself; it is a tale of humankind seen not as individuals, but as an aggregate of categories. The second is a memoir of humans seen as individuals, with all their flaws and foibles. It is the macro view vs. the micro view.

The most distressing thing is that we all have to live in both worlds; we have our families and friends, but we also cannot escape the things our governments, our religions and our employers do in our name.

The first book is Bloodlands, by Timothy Snyder, which recasts the central story of World War II — really from 1933 to 1948 — in a way which finally makes sense to me, and is a needed antidote for all the triumphalist D-Day feel-goodism you are weighed down by in endless TV documentaries about the war.

The first book is Bloodlands, by Timothy Snyder, which recasts the central story of World War II — really from 1933 to 1948 — in a way which finally makes sense to me, and is a needed antidote for all the triumphalist D-Day feel-goodism you are weighed down by in endless TV documentaries about the war.

We are too often deluded into thinking that World War II was a time in which America waged a “good war” against Nazism and won. I had always found this view indefensible, simple minded and ultimately jingoistic. The U.S. certainly had its part to play — and I don’t mean to denigrate the sacrifice of our soldiers, sailors and those on the homefront — but when I looked at the figures, it was hard to reconcile the idea that we were the major player when our war dead totaled half a million but the Soviet Union’s dead exceeded 12 million. Either they were terrible soldiers and ours were magnificently efficient, or the real war was not in Normandy, but in the Eastern Front.

But even my own prejudice about the war really being between Germany and Russia turns out to be a gross simplification.

The book is an accounting of all the dying that took place in the shifting-border areas between Germany and Russia — the areas that were sometimes Poland, sometimes Ukraine, Belarus and parts of the Baltic states, Romania and Hungary — death caused by the political choices and policies first of Stalin in the Soviet Union and then Hitler in Germany.

By the accounting of the author, they are culpable in the deaths of 14 million civilians. This is above and beyond the military deaths caused by the war itself. This was the deliberate starvation of Ukrainian farmers in the 1933, the “Great Terror” of 1938, in which Stalin wiped out his political enemies, rivals and phantoms of his paranoia, followed by the mass shootings in occupied Poland from 1939 to 1941, the starvation policy used by the Germans on 3.1 million Soviet prisoners of war and the intended extermination of Jews by Germans from 1941 to 1945. It is a dismal story of humanity’s inhumanity. These were not accidental deaths, but deaths of central planning and political purpose.

The overwhelming bulk of death during those years took place between the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop line that divided pre-war Poland in half, and the eastern borders of Ukraine and Belarus.

Snyder footnotes the exact counts, often village by village, with anecdotal horror stories of those shot, burned, gassed and garroted. One hardly turns the pages without choking and weeping.

From Snyder’s view, the war in Europe was not merely one between Nazi Germany and the Communist Soviet Union, but rather one in which Hitler and Stalin colluded in first wiping Poland off the map, splitting it between them in 1939 (the aforesaid Molotov-Ribbentrop line), and then, when Hitler’s plan to evict all the Poles and Jews from what was formerly western Poland got bogged down in difficulty (the plan to deport them all to the east, vaguely somewhere in the Soviet Union, perhaps Kazakhstan was nixed by Stalin), it turned into a plan to murder them all.

It should be noted that in Russia, the official dates of World War II are 1941 to 1945. They don’t acknowledge the invasion of Poland by Germany on Sept. 1, 1939 as the start of the war, because they were equally culpable in that dissolution of the state of Poland. But they start the conflict in 1941, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. Except, of course, that Hitler didn’t first invade the Soviet Union. He invaded what used to be eastern Poland, on the other side of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line, but had since been declared to be part of the Soviet Union — the formerly Polish part. For Stalin it made no difference that this was formerly Poland; now it was de facto part of his Soviet Union.

When Hitler’s army failed to take Moscow quickly, as his Blitzkrieg model had planned, the war turned into a protracted and mass slaughter of German and Soviet armies.

While we in the West call World War II “the good war,” in Russia they remember it as the Great Patriotic War, but in reality the whole thing should be called the Soviet-German war over the dismemberment of Poland.

To that bloody conflict, D-Day, Sicily, North Africa, Dunkirk, the Battle of Brittain were all basically a side-show. Our propaganda portrayed Hitler as seeking “world domination,” but that was never more than a comic-book arch-villain sort of plot. France and England were brought into the war because they had a defense treaty with Poland. Hitler would have preferred to avoid war with England and France. His beef was with Stalin over the land he wanted in Poland for German expansion — primarily to provide farming land and food for an expanding and industrialized Germany. Having to deal with England and France in the west was a pesky bother to him.

(The war in the Pacific, which happened concurrently, can be seen as primarily a separate war, beginning with Japanese invasions of Manchuria and China in the 1930s and ending after the war in Europe. The Pacific war was essentially America’s war, unlike the war in Europe.)

Back to the book: What makes it so dismal is not just the magnitude of the statistics — how many million shot in the back of the head here, so many million run through the death camps there — but the documented stories of individual deaths, or whole villages prisoned in churches that were then burned down, or men required to dig pits the length of two football fields, and then told to lie down in the graves, where they were shot, and layered like lasagne with another pile of bodies, shot, and another, and another, then covered up with dirt.

One fears turning the page in Bloodlands to find more starvation, more cold-blooded planning of mass murder, more mothers torn from their babies, more husbands worked to death in labor camps, while their parents were shipped off to Treblinka or Chelmno.

We too often think of the concentration camps as the place of the Holocaust, but Snyder makes clear that as many Jews were killed by bullets as by gas, and that the version of camp death we most often think of — say Auschwitz or Buchenwald — were not actually death camps, but rather holding camps in which death was a too-common byproduct. The real death camps were small facilities with no barracks, just changing rooms. The victims arrived by train, stripped of clothing and possessions and were herded directly into gas chambers where internal combustion engines piped carbon monoxide in, killing all in about 20 minutes of terror, and then the corpses were carried out an burned in huge pyres, kept fired up like so many charcoal grills. Treblinka was built exclusively to empty out the Warsaw ghetto. When that was accomplished, Treblinka was closed down. The extermination camp at Chelmno did the same thing for the Jews of the Lodz ghetto. The industrialized purposefulness of such factories is all the more chilling.

We tend to think of Hitler’s atrocities as being 6 million Jews killed in the Holocaust. And in terms of ethnic cleansing, it is one of the most ghastly in human history, but the suffering was also spread out in the period Snyder covers, from so-called kulaks in Ukraine to Polish officers massacred after the division of Poland in 1939, to dissidents and potential dissidents in the Soviet Union. Some 60 million people died in those years from political violence, less than half of them were military. That was 3 percent of the world’s population at the time.

One of the arguments one hears from the so-called Holocaust deniers, is that the Shoah was simply too vast to be believed. No humans could possibly have exterminated that many people in that short a time. Yes, they say, Hitler had anti-Semitic policies and maybe a few were killed, but the vast numbers were not believable. One has to laugh at this argument, not only in the face of Snyder’s careful accounting, but in the long view of history, and the slaughter of conquered peoples from the dawn of time. The Holocaust was not a singular event, but something like the standard order of things. This is what people do to each other, over and over and over. One must remember the wholesale extermination of city populations by Genghis Khan, the pyramids of skulls of Tamerlane. The slaughter of Cathars in the 13th century, or earlier, of the Wu Hu in China in the Fourth Century. One voice echoes through history: Carthago delenda est. So, ethnic cleansing continues in our own time, whether in Rwanda or Sudan or Cambodia.

I have gone on is rather more length than I had intended. The book is overwhelming, the pessimism it engenders is oppressive. I do not hope for a brighter future; I cannot knowing the lessons of history.

But I can put the book down when finished, and pick up another, one that gives me as much pleasure as Bloodlands gives me pain.

And here’s where the whiplash may hit you, too.

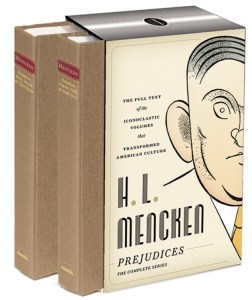

Because the next tome I picked up was H.L. Mencken’s three autobiographical books, published as a single volume by the Library of America. I cannot convey to you quite the pleasure to be had by reading Mencken. His writing is full of the vigor and intellectual energy of a man in love with life and in love with the way language can convey that love.

Because the next tome I picked up was H.L. Mencken’s three autobiographical books, published as a single volume by the Library of America. I cannot convey to you quite the pleasure to be had by reading Mencken. His writing is full of the vigor and intellectual energy of a man in love with life and in love with the way language can convey that love.

It is not that everything is wonderful in Mencken’s life, but rather that the failings of human existence — seen as the acts of individuals, rather than classes of people — are at bottom so entertaining.

It is particularly his volume on his early newspaper work that fills me with joy. Newspaper Days covers the years from about 1899 to 1906, and lets me know that journalism hadn’t changed much from his day to mine (that it is now nearly extinct is another sorrow I feel).

Just as I dreaded each new chapter in Bloodlands, I check to see how many more pages I have left of Mencken and dread instead the final page, when my pleasure will come to its end.

The Library of America had previously published his six series of Prejudices, which were collected essays, always a joy to read, even when what he says might be outrageous and, well, prejudiced. At bottom, Mencken is clear-eyed and unbowed, and we value his fellowship, even in print, as we might value it sitting on a barstool next to him, sharing banter over a foamy beer. You might not agree with Mencken’s opinions, but they were always magnificently expressed, in a kind of journalistic language raised to the level of poetry.

I have his three volume The American Language, which is about as entertaining a scholarly book as you could find. Thorough, amused and amusing, it is indispensable.

The best way I can convey to you the qualities of Mencken’s writing, and of his mind, is to quote him. Here is a section from Newspaper Days, in which he talks about the artists employed back at the turn of the century to illustrate newspaper stories, before the days when photographs could be easily reproduced. As editor, he had to deal with their eccentricities.

After a few anecdotes about artists getting themselves into trouble and drink, he reminds us that:

“The cops of those days, in so far as they were aware of artists at all, accepted them at their own valuation, and thus regarded them with suspicion. If they were not actually on the level of water-front crimps, dope-pedlars and piano-players in houses of shame, they at least belonged somewhere south of sporty doctors, professional bondsmen and handbooks [obsolete slang clarification: bookies]. This attitude once cost an artist of my acquaintance his liberty for three weeks, though he was innocent of any misdemeanor. On a cold Winter night he and his girl lifted four or five ash-boxes, made a roaring wood-fire in the fireplace of his fourth-floor studio, and settled down to listen to a phonograph, then a novelty in the world. The glare of the blaze, shinning red through the cobwebbed windows, led a rookie cop to assume that the house was afire, and he turned in an alarm. When the firemen came roaring up, only to discover that the fire was in a fireplace, the poor cop sought to cover his chagrin by collaring the artist, and charging him with contributing to the delinquency of a minor. There was, of course, no truth in this, for the lady was nearly forty years old and had served at least two terms in a reformatory for soliciting on the street, but the lieutenant at the station-house, on learning that the culprit was an artist, ordered him locked up for investigation and he had been in the cooler three weeks before his girl managed to round up a committee of social-minded saloonkeepers to demand his release. The cops finally let him go with a warning, and for the rest of that Winter no artist in Baltimore dared to make a fire.”

The book moves forward with speed and irony, full of vivid expressions and entertaining stories. Mencken recalls cops and judges, editors and pressmen, drummers for patent medicines and press agents of dubious veracity, kindly murderers and scapegrace yobs of all descriptions, many of which Mencken counted as his special angels of the kind of humanity he most valued. He detested all cant and corporate or governmental doublethink, and anyone who would put life into a file cabinet alphabetically.

The book moves forward with speed and irony, full of vivid expressions and entertaining stories. Mencken recalls cops and judges, editors and pressmen, drummers for patent medicines and press agents of dubious veracity, kindly murderers and scapegrace yobs of all descriptions, many of which Mencken counted as his special angels of the kind of humanity he most valued. He detested all cant and corporate or governmental doublethink, and anyone who would put life into a file cabinet alphabetically.

It is the pleasure of coming across his book after reading Bloodlands that restores the oxygen to a world otherwise noisome with the mephitic stench of death. And reminds us that it is a grace that we live in a world of individuals rather than in the statistical world of categories and proscription lists. Grace is what keeps us alive.