Quartet for the End of Time

The date is Jan. 15, 1941. Snow blankets the ground of a Nazi prisoner of war camp near Gorlitz, Germany, and the temperature is below zero. But in unheated Barracks 27, several hundred prisoners have gathered to hear a new piece of music. German officers occupy the front row.

“The cold was excruciating, the stalag was buried under snow,” wrote the composer of the music heard that night. “But never have I had an audience who listened with such rapt attention and comprehension.”

The prisoners and officers heard the quartet begin with a clarinet playing the same notes a blackbird sings. The answer came from a violin imitating a nightingale. Meanwhile a piano and cello created the harmonic nimbus that sits as still as the surface of a windless pond.

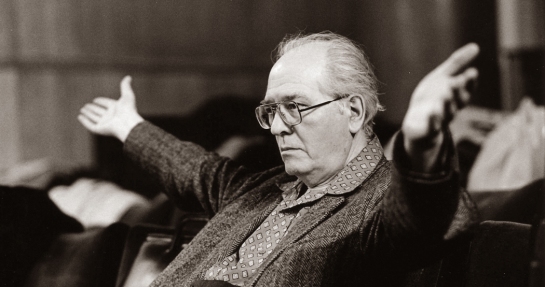

It was the “Liturgy of Crystal” and the opening movement of French composer Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time, one of the most miraculous pieces of music ever written.

Messiaen wrote of that opening, “Between three and four in the morning, the awakening of birds: a solo blackbird or nightingale improvises surrounded by a shimmer of sound, by a halo of trills lost very high in the trees. Transpose this onto a religious plane and you have the harmonious silence of heaven.”

The composer, a devout Roman Catholic, had been the organist at Sainte-Trinite Church in Paris. But his religion was less concerned with dogma than with revelation: He was a religious mystic.

Messiaen, an odd little man, had joined the French army as a medic and was captured by the Germans in 1940. Herded into cattle cars, he had no food and little clothing but filled his knapsack with musical scores. When he was transferred to Stalag 8A near Gorlitz he found a violinist, a cellist and a clarinet player and — more important — he found Karl-Albert Brull, a German guard who loved music.

Brull bought manuscript paper for Messiaen, found him an empty barracks to work in, posted a guard to keep the composer from interruptions and encouraged him to write music. He also counseled the captured Jews not to escape, arguing that their life in Vichy France would be more dangerous than life inside the stalag.

Soon after the now-famous concert, Brull arranged to have Messiaen repatriated to France.

“As musicians, you had no guns,” an officer said.

The Quartet for the End of Time spun out from its prison birth and became one of the celebrated musical compositions of the 20th century, but it always maintains its ability to astonish and shock.

“When I first played it, 30 years ago,” says cellist Yehuda Hanani, “it was as if someone took me to the moon and said, ‘This is what they write here.’ It was so different.

“It was written in the early ’40s, but it is still considered contemporary music. It transcends time.”

It was so avant-garde that it wasn’t performed in New York until the 1970s. Hanani was cellist at the 92nd Street Y in New York when Quartet premiered there. During that New York performance, Messiaen was in the wings, listening, “with tears streaming down his cheeks,” Hanani recalled.

During the war, Messiaen, who died in 1992, saw civilization crumbling around him and thought of it as the end of the world. “And he gave it a religious spin,” Hanani said. “For him this was the end of time, and you can see him experiencing it, but rather than being destroyed by it, or portraying the cruelty and savagery of war, like Picasso did in Guernica or Shostakovich in his symphonies, which are so devastating, he transcends this whole thing and goes somewhere else.”

But the quartet’s end of time also is musical: Messiaen was interested in non-Western music and the songs of birds, and he attempted in the quartet to make music without the normal rhythm of bars and meter. He manages to slow time to the point that, musically, it almost stops.

“Like the pulse of animals that hibernate,” Hanani said. And when it moves forward, it does so with the violence of apocalypse, irregular and fitful.”

Apocalypse contains not only monsters and cataclysms,” Messiaen wrote, “but also moments of silent adoration and marvelous visions of peace.”

There are many recordings out there, but one of the best, still available, is by the long-disbanded group Tashi, with Peter Serkin, Ida Kavafian, Fred Sherry and Richard Stoltzman. It was recorded in 1975.

This is an amazing story. I’m listening to Tashi now on YouTube.