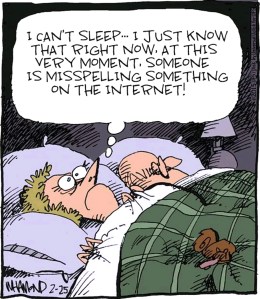

I was an English major and I’m married to an English major and it’s hard being an English major and only getting harder. An English major feels genuine pain hearing the language abused, mal-used, corrupted and perverted.

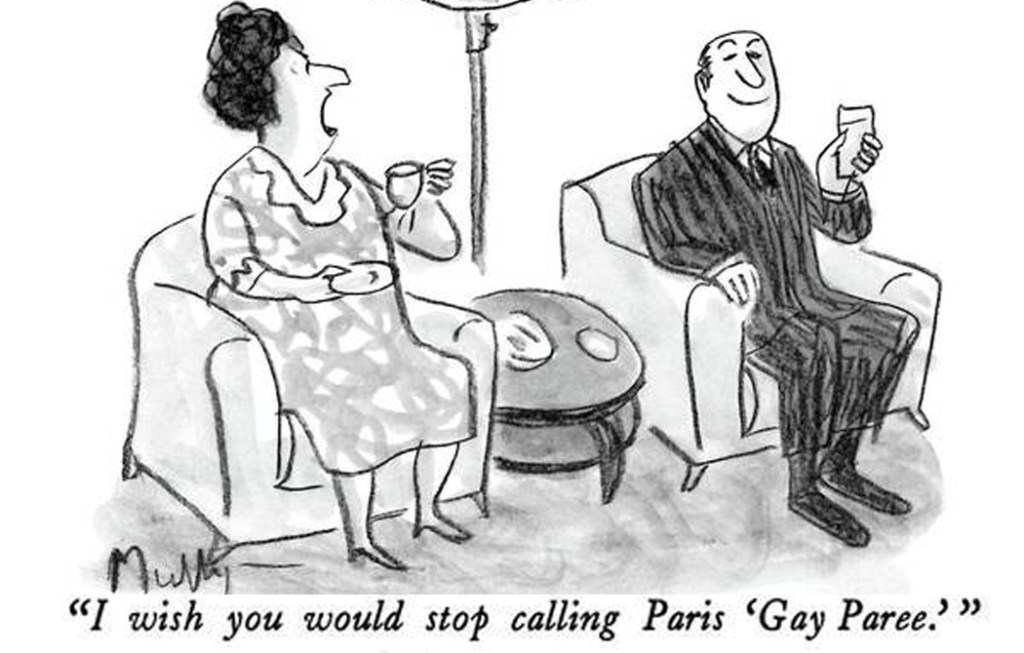

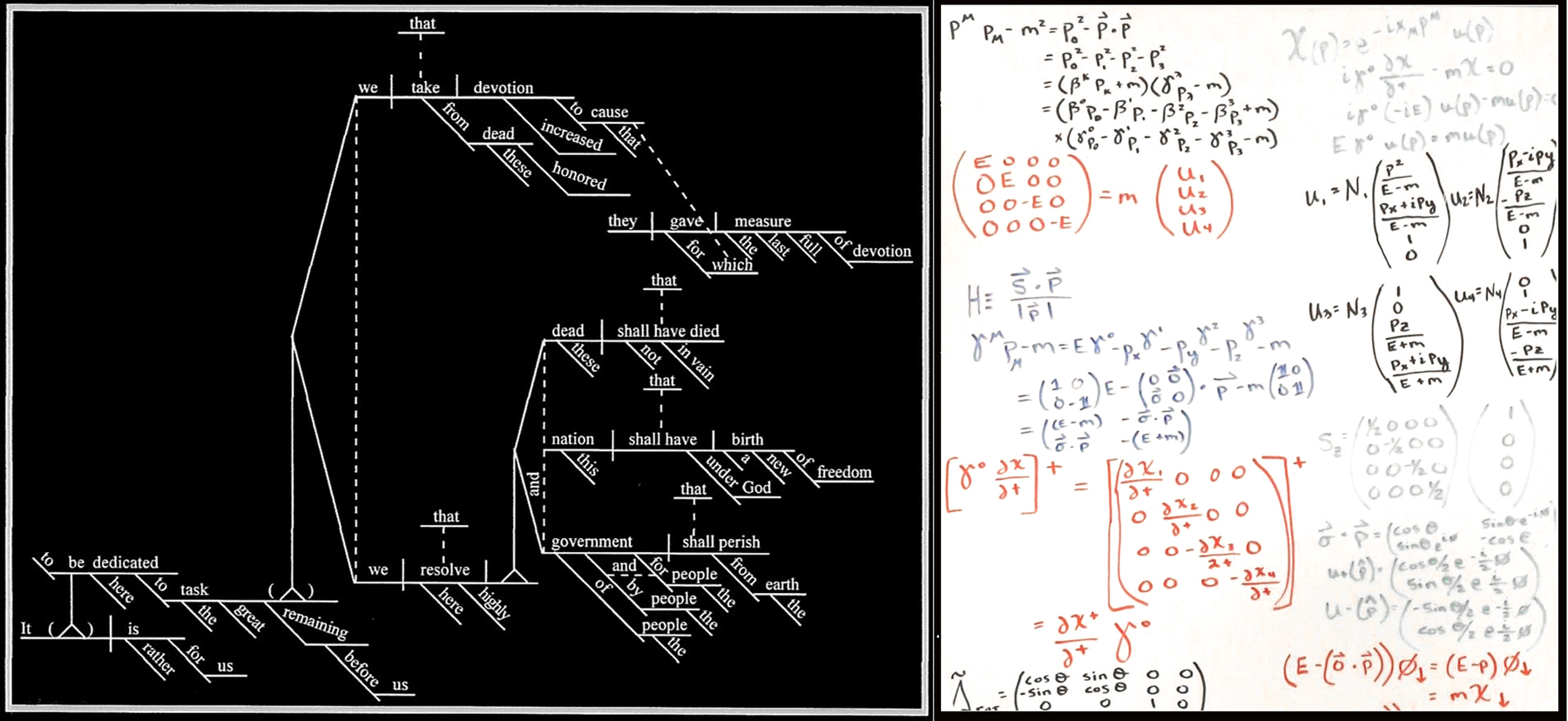

I’m not talking here about outdated grammar rules and a fussy sort of prisspot pedantry. As a matter for fact, one of the most persistent pains a true English major suffers is such misplaced censure, especially when interrupting a casual speaker to let them know that “them” is plural and “speaker” is singular. In my book, this is merely rude. A caboose preposition is nothing to lose sleep over.

No, what I’m writing about here is are things that are genuinely ugly or purposely unclear, or overly trendy, to the point of losing all meaning. You know — politics. That and corporate language, or management speech — which I call “Manglish” — is a great corrupter of speech.

“We have assessed the unprecedented market shifts and have decided to pivot this company’s new normal to a deep-dive into a robust holistic approach to our core competency, circling back to a recalibrated synergy amid human capital in solidarity with unprecedented times.”

Committees try to make language sound profound and wind up writing piffle. I’m sure it was a committee that agreed in Iredell County, N.C., to make the county slogan, “Crossroads for the future.” I do not think that word means what you think it means.

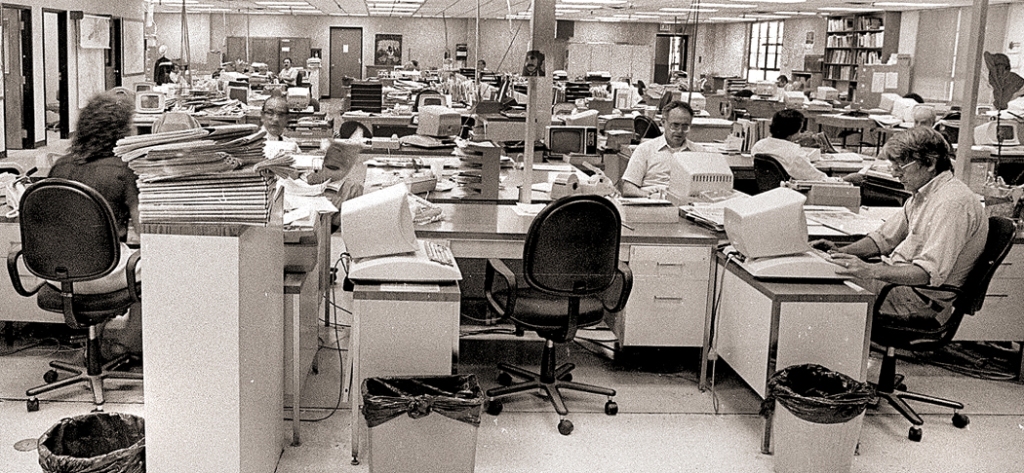

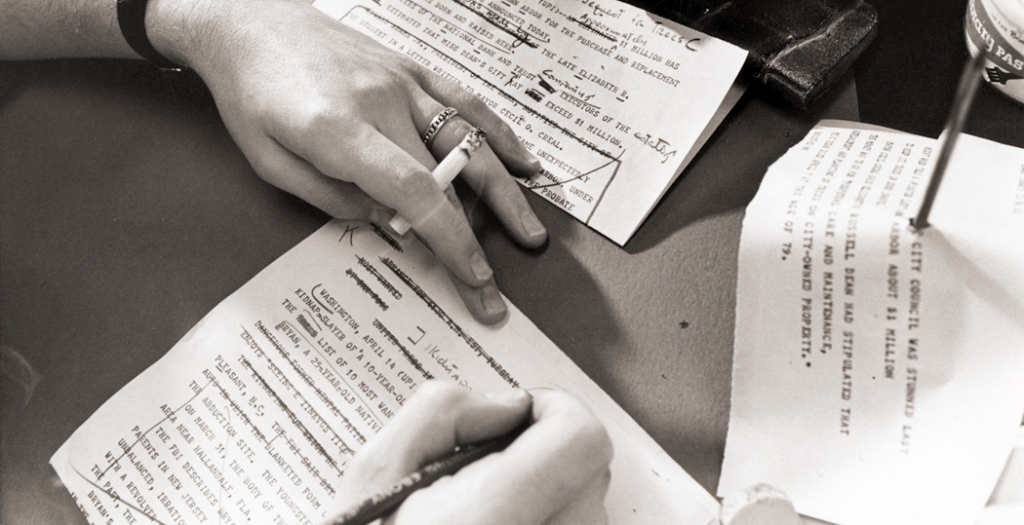

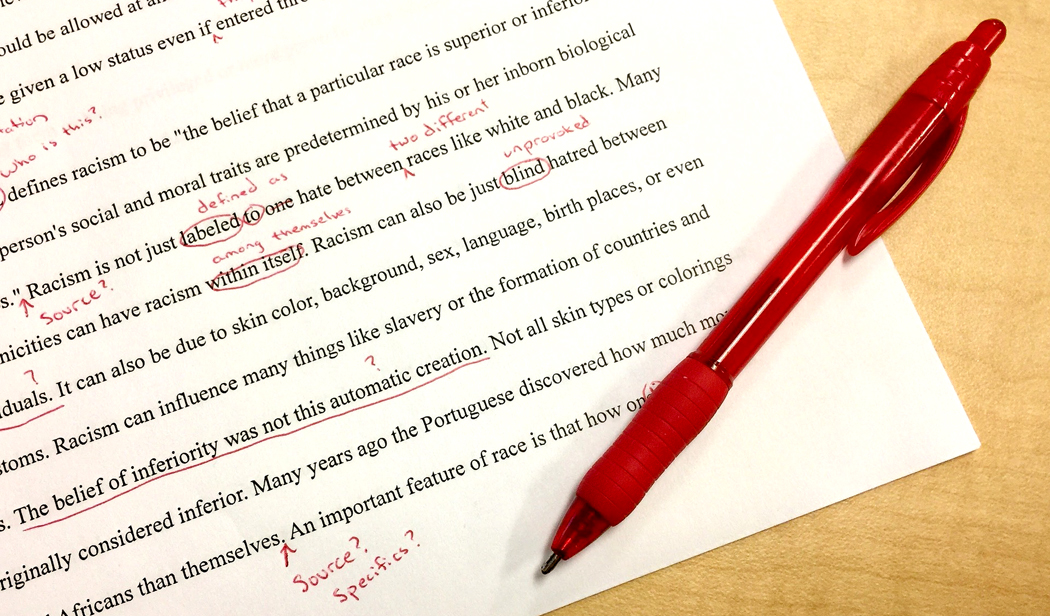

I wrote for a daily newspaper and language was my bread and butter, but the higher you go up the corporate ladder, the worse your words become. I remember the day they posted a new “mission statement” on every other column in the office, filled with buzz-word verbiage that didn’t actually mean anything. I looked at my colleague and said, “If I wrote like that, I’d be out of a job.”

But it isn’t just Manglish. Ordinary people are becoming quite lax about words and meanings. Too often, if it sounds vaguely right, it must be so. And you get “For all intensive purposes,” “It’s a doggy-dog world,” being on “tender hooks,” or “no need to get your dandruff up.”

“I’ve seen ‘viscous attack’ too many times recently,” my wife says. “It gives me an interior pain like a gall bladder attack.”

And the online world is full of shortcuts, some of which are quite clever, but most of which are just barbarous. An essay about digital usage is a whole nother thing. Not room here to dive in.

But, there is a world of alternative usage that is not standard English, that any real English major will welcome as adding richness to the mother tongue. Regionalisms, for instance. Appalachian dialect: “I’m fixin’ to go to the store;”— actually, that is “stoe,” rhymes with “toe” — “I belong to have a duck;” “I have drank my share of Co-Cola.”

And Southern English has served to solve the historical problem of having lost the distinction between the singular “thee,” and the plural “you,” with the plural “you all,” or “y’all.” Although, more and more “y’all” is now being used also for the singular, and so is becoming replaced with “all y’all.” Keep up, folks.

Then, there’s African-American English, which has enriched the American tongue immensely, as has Yiddish: “Shtick,” “chutzpah,” “klutz,” “schmooze,” “tchotchke.”

Regionalisms and borrowings are like idioms. Sometimes they don’t really make sense, but they fall comfortably on the tongue. “Who’s there?” “It’s me.” Grammatically, it would be proper to say “It is I,” but no one not a pedant would ever say such a thing. The ear is a better arbiter than a rulebook.

George Orwell ended his list of rules for writing with the most important: “Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”

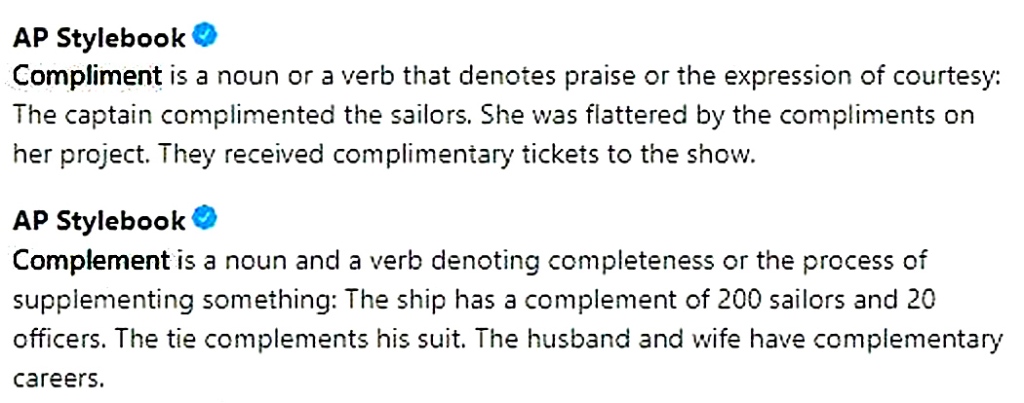

English is a happily promiscuous tongue and so much of the richness of the language comes from borrowings. But there are still other problems: bad usage, misuse of homonyms, loss of distinctions. The English major’s ears sting with each onslaught.

What causes our ears to burn falls into three broad categories. Things that are just wrong; things that are changing; and things that offend taste. Each is likely to set off an alarm ping in our sensitive English major brains.

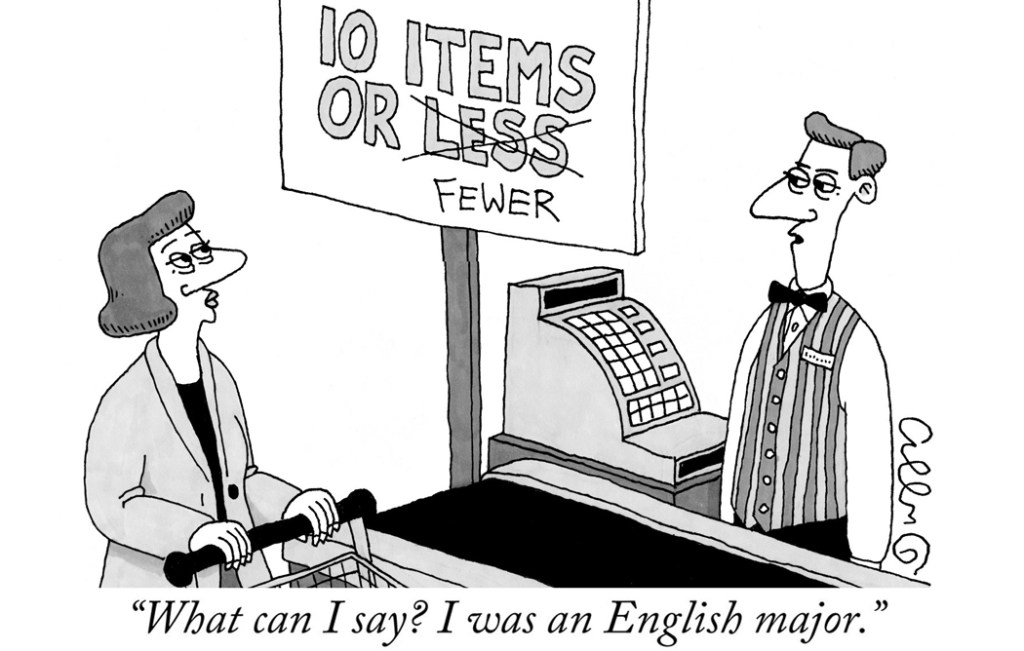

Every time I go to the grocery store I am hit with “10 items or less.” Few people even notice, but the English major notices; we don’t like it. “Comprised of” is a barbarism. “Comprises” includes all of a certain class, not some items in a list of choices. I feel slapped on the cheek every time I come across it mal-used.

And homonyms: a king’s “rein,” or a book “sited” by an article, or a school “principle” being fired. It happens all the time. It is endemic online. “Their,” “they’re,” “there” — do you know the difference? “You’re,” “your?” Most young’uns IM-ing on their iPhones don’t seem to care.

And fine distinctions of usage: I am always bothered when I see a murderer get “hung” in an old Western, when we know he was “hanged.”

Again, most Americans hardly even notice such things. They all get by just fine not caring about the distinction between “e.g.” and “i.e.” In fact, they can get all sniffy about it.

I know a former medical transcriptionist who typed up a doctor’s notes each day, and would correct his grammar and vocabulary. She corrected the man’s “We will keep you appraised of the outcome,” with “apprised,” and each time, he would “correct” that back to “appraised.” Eventually, she gave up on that one.

English majors know the difference between “imply” and “infer,” and it causes a hiccup when they are mixed up. “Disinterested” mean having no stake in the outcome; “uninterested” means you cannot be arsed. They are not interchangeable.

We EMs cringe when we hear “enormity” being used to mean “big,” when it actually means a “great evil.” And “unique” should remain unique, unqualifiable. Of course, “literally” is used figuratively literally all the time. Something is not “ironic” simply because it is coincidental.

I hear the phrase “begging the question” almost every day, and always misused. It refers to circular reasoning, not to “raising the question.” I hold my ears and yell “Nya-nya-nya” until it is over.

Some things, which used to be wrong, are slowly being folded into the language quietly, and our EM ears may still jump at hearing them. “Can” and “may” used to mean distinct things, but that difference was lost at least 100 years ago. We can give that one up. And “hopefully” used to be a pariah word, but we have to admit, it serves a grammatical function and we have to let it in, however grudgingly.

My wife is particularly sensitive to the non-word, “alot.” She absolutely hates it. I understand, although I recognize a need for it. “A lot” is a noun, and sometimes we use it as an adjective: “I like chocolate a lot.” Perhaps “alot” will eventually become an adjective. Not for Anne.

People are different and have differing talents. We seem to be born with them. Some people grasp mathematics in a way a humanities student will never be able to match. Some have artistic or musical talent. We can all learn to play the piano, but only certain people can squeeze actual music out of the notes.

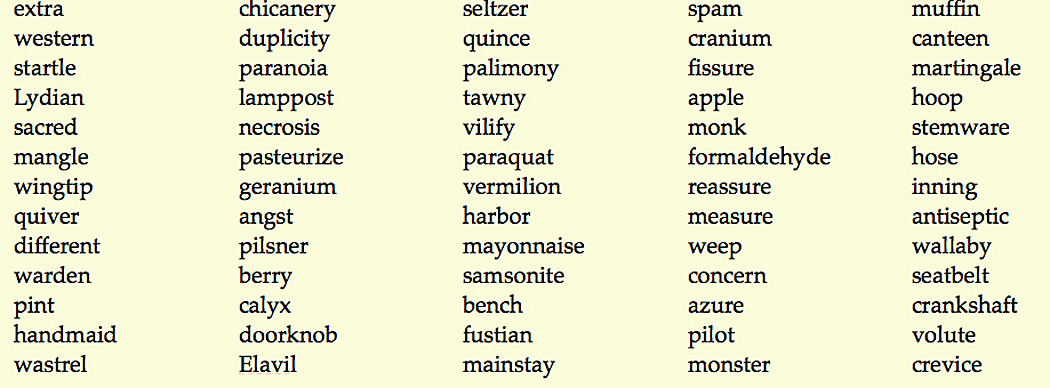

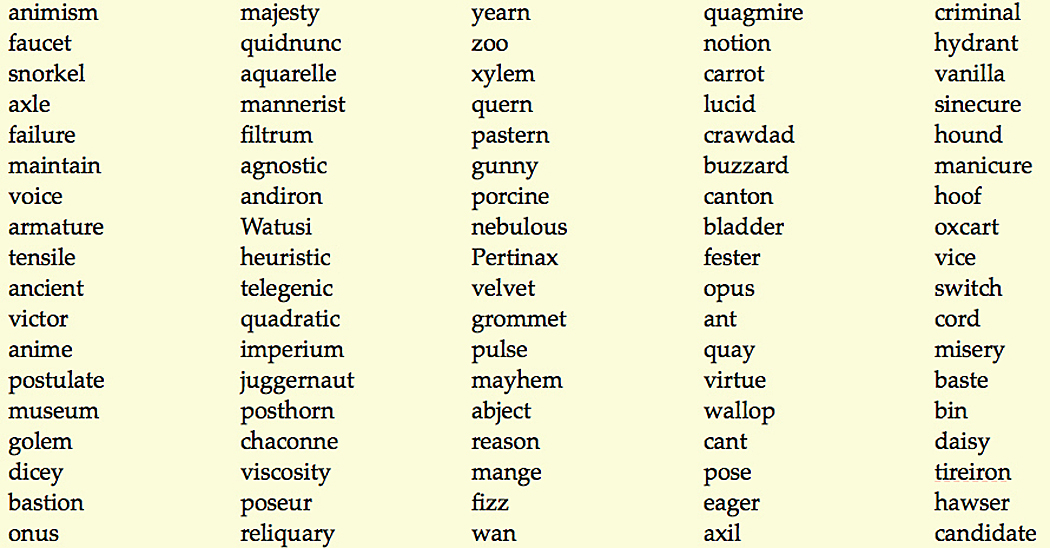

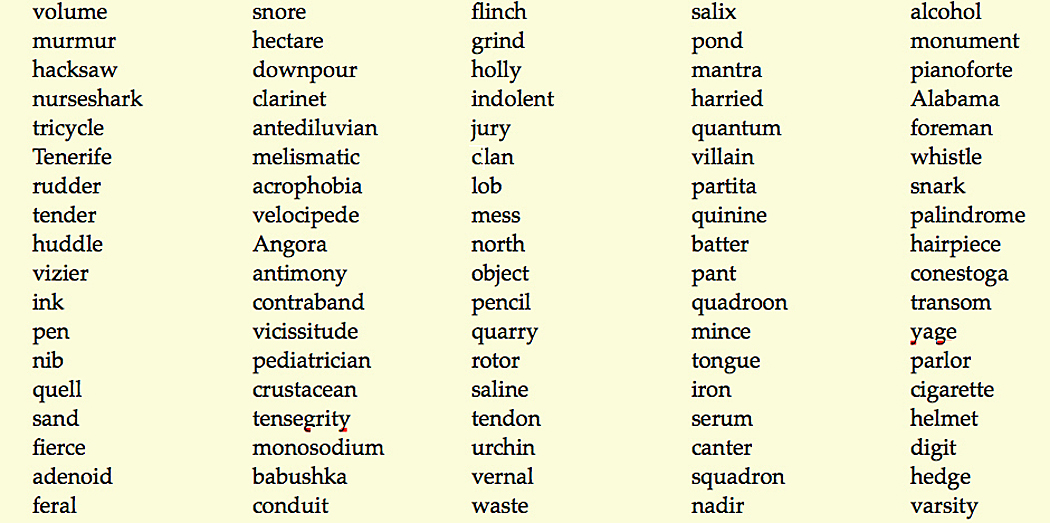

And each of us can learn our native tongue, but some of us were born with a part of our brains attuned to linguistic subtlety. We soaked up vocabulary in grade school; we won spelling bees; we wrote better essays; we cringe at the coarseness of political speech. Language for the born English major is a scintillating art, with nuance and emotion, shadings and flavors. We savor it: It is not merely functional.

(I loved my vocabulary lessons in grade school, and when we were asked to write sentences using that week’s new words, I tried to use them all in a single sentence. People who show off like that often become writers.)

Just as my piano playing, even when I learned whole movements of Beethoven sonatas, was always the equivalent of speaking English as a second language, my best friend, Sandro, could sit at a piano and every key was fluent, natural, and expressive. It was a joy to hear him play; a trial for me just to hit the right notes.

I am saying that those of us who gravitate to speech, writing, and language in general, have something akin to that sort of talent. It is inherent, and it can be a curse. Bad language has the same effect on our ear as a wrong note on a piano.

We can feel the clunkiness of poorly expressed thoughts, even if they are grammatical. Graceful language is better. And so, we can rankle at awkward expressions.

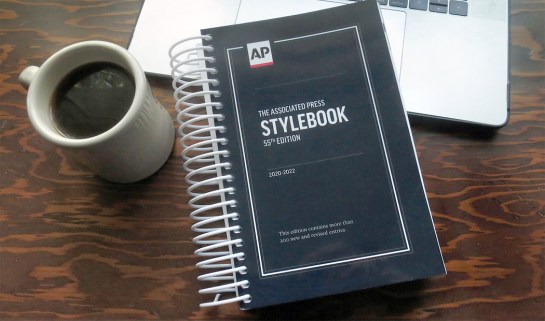

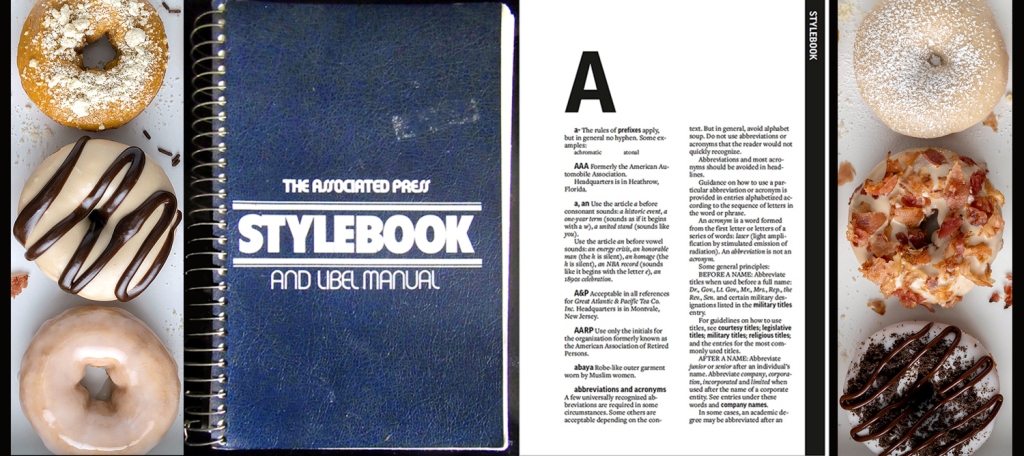

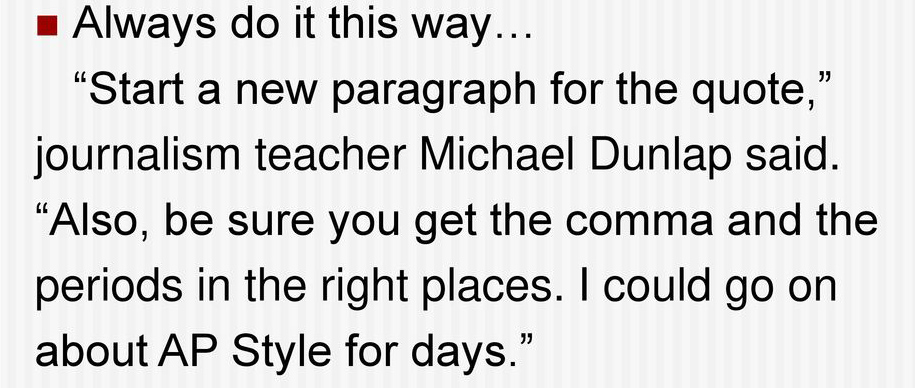

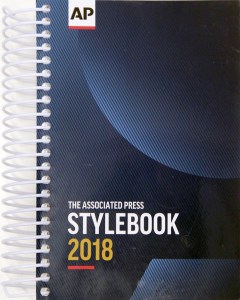

I have a particular issue, which I share with most aging journalists, which is that I had AP style drummed into me — that is, the dicta of the Associated Press Stylebook, that coil-bound dictator of spelling, grammar and usage. One understands that AP style was never meant to be an ultimate arbiter of language, but rather a means of maintaining consistency of style in a newspaper, so that, for instance, on Page 1 we didn’t have a “gray” car and on Page 3 one that was “grey.”

And so, the rules I lived by meant that there was no such thing as 12 p.m. Is that noon or is that midnight? Noon was neither a.m. nor p.m. Same for midnight. They had their own descriptors. “Street” might be abbreviated in an address, but never “road.” Why? I never knew, but in my first week on the copy desk I had it beaten into me when I goofed.

“Back yard” was two words, but one word as an adjective, “backyard patio.” Always. “Air bag,” two words; “moviegoer, one word. “Last” and “past” mean different things, so, not “last week,” unless Armageddon is nigh, but “this past week.” Picky, picky.

I had to learn all the entries in the stylebook. The 55th edition of the AP Stylebook is 618 pages. And this current one differs from the one I had back in 1988; some things have changed. Back then, the hot pepper was a “chilli pepper,” and the Southwestern stew was “chili.” I lived and worked in Phoenix, Ariz., and we all understood this would get us laughed off the street, and so exceptions were made: yes, it’s a chile.

Here I am, nearly 40 years later, and retired for the past 12 years, and I still tend to follow AP style in this blog, with some few exceptions I choose out of rebellion. But I still italicize formal titles of books, music and art, while not italicizing chapter names or symphony numbers, per AP style. I still spell out “r-o-a-d.” It’s a hard habit to break.

The online world seems to care little for the niceties of English. We are even tending back to hieroglyphs, where emojis or acronyms take the place of words and phrases. LMAO, and as a card-carrying alte kaker, I often have to Google these alphabet agglutinations just to know what my granddaughters are e-mailing me. Their seam to be new 1s each wk.

And don’t get me started on punctuation.