When Pablo Picasso painted Guernica, he knew he was making a monument. When Milton wrote Paradise Lost, he knew he was writing for the ages. When Bergman filmed Seventh Seal, he knew he was saying something important and not merely entertaining us with a cool story.

Art is often made with large purpose. Artists may work a whole lifetime to be able to sum things up in a major piece, or group of pieces, like the Isenheim Altarpiece of Grünewald, or Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu.

In these cases, the art becomes an entity in itself, a thing produced. It takes on a life beyond its maker’s; it is a milepost in cultural history. We look to it not only for beauty, but for wisdom, for inspiration, for a sense that there is something large which we all share as humans.

On the other end of the spectrum are the snapshots we take of our families, on birthdays, on vacations, on weddings. As such, the photographs are seldom seen as esthetic objects, but rather encapsulated memories — something to hold fast a fleeting moment of importance to our singular lives. They may capture something intensely human, but that is not their primary purpose.

On the other end of the spectrum are the snapshots we take of our families, on birthdays, on vacations, on weddings. As such, the photographs are seldom seen as esthetic objects, but rather encapsulated memories — something to hold fast a fleeting moment of importance to our singular lives. They may capture something intensely human, but that is not their primary purpose.

(It is always fun to scavenge anonymous snapshots to find glimmers of the idiosyncratic or the universal, that is, to see them as if they were intended as art. But that is a piece of active curation on our parts, as if we were the artists ourselves, editing the random into a coherent message. The family photos were never meant to hang in art galleries.)

Even if a painter isn’t making a Sistine Chapel, if he is a professional, he is creating a commodity — an object that can be sold. And even if it’s not bought, the thing exists as a thing. There it is, framed and hanging on a wall, with track lighting making it glow jewel-like in the gallery.

But there is something between these two poles — between commodity and snapshot. It is the artist’s working sketch, never meant to be sold, never meant even to be seen. It is either the artist trying out ideas for a painting, or — and this is even more important — just keeping his hand in.

There is something of the throwaway in such noodling, but there is also something of value we shouldn’t underestimate.

We often forget that there is an intimate connection between art and the experience of living. It has been made easier to forget because in the last half century or so, a good deal of art has been made simply about art, about its materials, its limits, its meaning, its history. But through most of that history, art was about the world. Whether it was landscape or still life, whether portrait or history painting, it was meant to reflect something of our common experience of life.

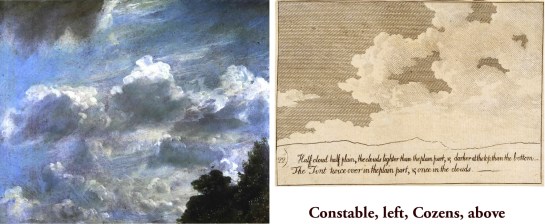

Even when art has been about art, it has been about the experience, in life, of thinking about art. There is an unbreakable connection between experience and its image.Which takes me back to those sketches. Whether it is Picasso doodling on a napkin or Turner washing light watercolor pigment over rag paper, it is — aside from any commercial intention — an effort by the artist to make the connection with the world. To see, and see clearly.

Photography, as much as painting, has its monuments, whether it is an Edward Weston pepper or Ansel Adams’ Moonrise Over Hernandez, or more recently, the giant photomurals of Thomas Struth or Andreas Gursky. They are the opposite of family photos.

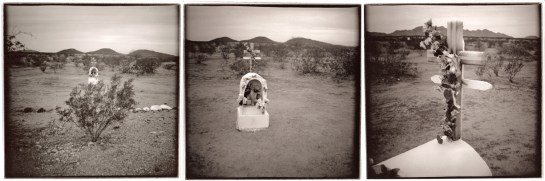

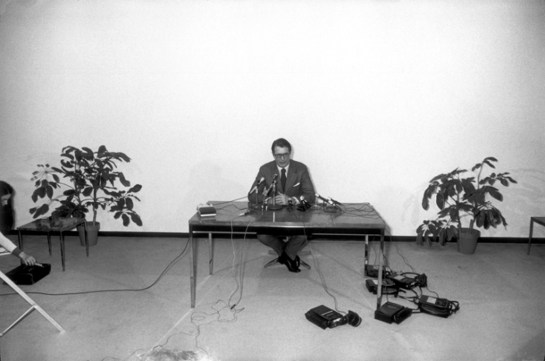

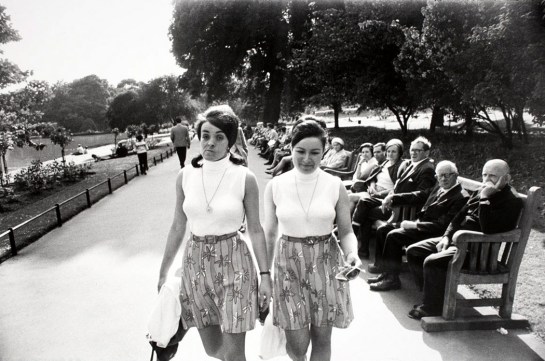

But there is a middle ground in photography, also. It is the equivalent of an artist sketching. Photographer Lee Friedlander calls it “pecking.” It is the quick, improvisatory snapping of bits of the world, to see what is there.

With is 35mm rangefinder Leica camera, Friedlander says, “you don’t believe you’re in the masterpiece business. It’s enough to be able to peck at the world.”

Only afterwards, going through his accumulation, does he edit and pick a few that stand on their own to be published or to be exhibited. But the interesting part, to Friedlander, is the engagement with the world.

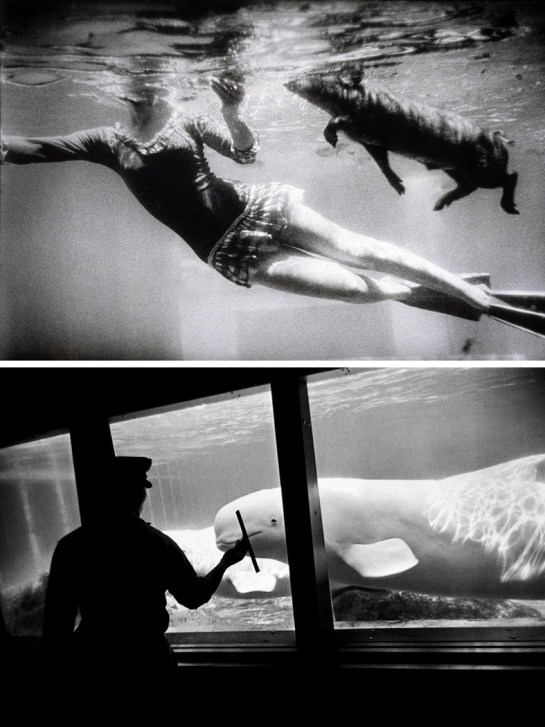

“I take more to the subject than to my ideas about it. I am not interested in any idea I have had, the subject is so demanding and so important,” he says. “Sometimes just the facts of the matter make it interesting.”

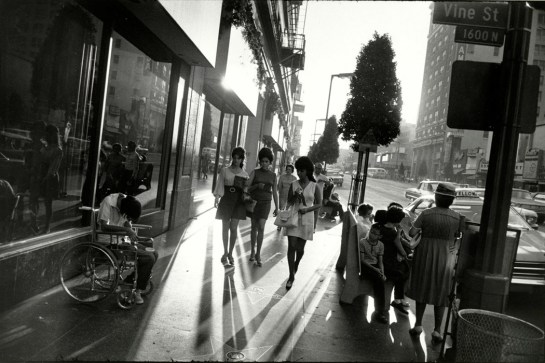

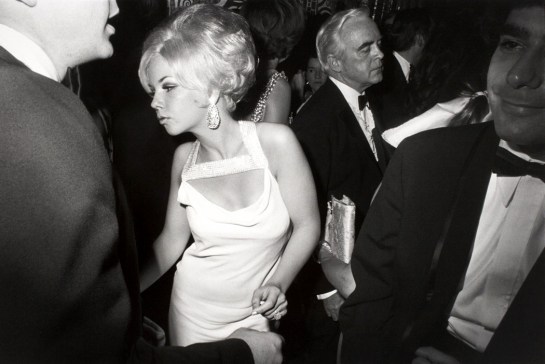

Friedlander is amazing in that his peckings are often so visually rich and complicated that they are nearly as Baroque as a painting by Rubens. Action seems to be in every corner of the frame.

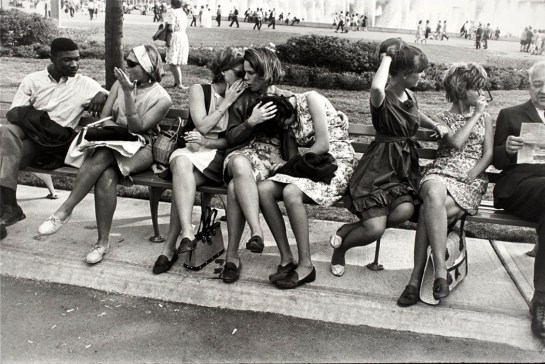

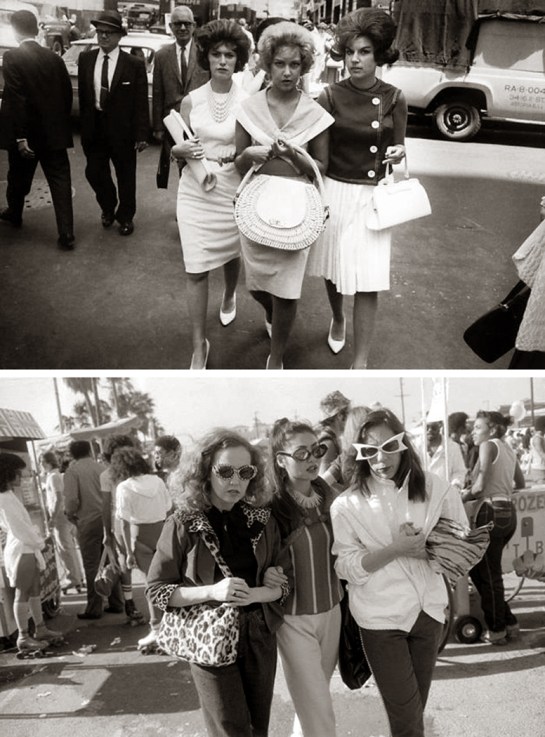

But you don’t have to be an artist as good as Friedlander to engage with the things of this world. Making photographs is a way of seeing, similar to sketching. It is about paying attention. We can focus on the details.

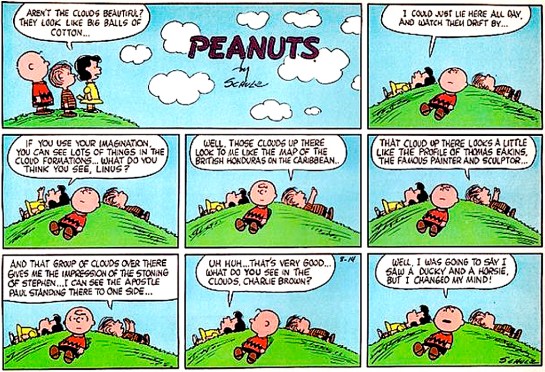

For many Americans — maybe most humans anywhere — only use their eyes for useful things. They see the road they drive on, the could that tells them it will rain, the house, the car, the coat closet. When they make a snapshot for the family album, it is enough to be able to name the items in the picture — that is Uncle Vern, that is the house we used to live in, that is my first car — and beyond the naming of the subject, we don’t really pay attention to what is there. Most probably, we have framed the image so the house or the uncle stands dead center in the frame.

Frielander talks about the potency of the photograph describing what is either his experience when he was a boy with his first camera, or perhaps anyone’s similar experience: “I only wanted Uncle Vern standing by his new car (a Hudson) on a clear day. I got him and the car. I also got a bit of Aunt Mary’s laundry and Beau Jack, the dog, peeing on a fence, and a row of potted tuberous begonias on the porch and seventy-eight trees and a million pebbles in the driveway and more. It’s a generous medium, photography.”

For Friedlander, his life work became making all these disparate bits harmonious in the frame. Again, like a Rubens.

For most of us, these pecked pictures are mostly details. They are not the grand view or the concatenated whole, but the tiny bits out of which the larger scene is built. Most of us pay attention only to the whole, when we pay attention at all; for most Americans — maybe most humans anywhere — only use their eyes for useful things. They see the road they drive on, the cloud that tells them it will rain, the house, the car, closet. But every house has a door, and every door a door-handle; every car has tires and every tire a tread and each tread is made up of an intricate series of rubber squiggles and dents. Attention must be paid.

Paying attention to the details means being able to see the whole more acutely, more vividly. The generalized view is the unconsidered view. When you see a house, you are seeing an “it.” When you notice the details, they provide the character of the house and it warms, has personality and becomes a Buberesque “thou.” The “thou” is a different way of addressing the world and one that makes not only the world more alive, but the seer also.

(It doesn’t hurt that isolating detail makes it more necessary to create a design. You can make a photo of a house and just plop it in the middle of the frame and we can all say, “Yes, that’s a house,” and let the naming of it be the end-all. But if you find the tiny bits, they have to organize them in the frame to make something interesting enough to warrant looking at.)

Sectioning out a detail not only makes you look more closely, but forces your viewer to look more closely, too. Puzzling out what he sees without the plethora of context makes him hone in on its shape, color, and texture. It is a forced look, not a casual one.

This is a rich world, profound in detail, millions of species, visual patterns in every rock and cloud. Each bit of rust on a grate is intense, when noticed. And noticing is what “pecking” is all about. With my own peckings, I am not making any argument for them as art; they will not be hanging in a gallery. I make them for myself, to force me to pay attention to the minutiae that are the bricks of the visual world they inhabit. And paying attention is a form of reverence.

Click to enlarge any image