The house is full of books. There is not a room in it, including the bathroom, that does not contain a bookshelf. Even the hallway has a floor-to-ceiling at the far end.

The kitchen has cookbooks; the bedroom has those I’m currently reading or have recently read; the office has one wall covered with poetry, another shelf filled with classical authors and a third wall plastered, not with books, but with CDs. The living room has the large, coffee-table art books and all my musical scores. Even the laundry room at the back of the house keeps an overflow. I just bought a new six-foot-tall shelf for it to keep up with the onslaught.

The kitchen has cookbooks; the bedroom has those I’m currently reading or have recently read; the office has one wall covered with poetry, another shelf filled with classical authors and a third wall plastered, not with books, but with CDs. The living room has the large, coffee-table art books and all my musical scores. Even the laundry room at the back of the house keeps an overflow. I just bought a new six-foot-tall shelf for it to keep up with the onslaught.

The question arises: Why do we keep so many books? What is the purpose of holding on to so many, even some we finished reading decades ago and almost certainly will never consult again? Is it simply hoarding? Is it nostalgia? Is it insulation, making the outer walls of the house thicker against the winter cold?

Many years ago, my wife invented a term for us. We had gone well beyond being bibliophiles. We were officially “bibliopaths;” it was now a pathology.

I remember the home of a favorite college professor. I was young and in love with learning and when invited to his home, I marveled at the walls lined with board-and-brick homemade shelves, stuffed with all the arcane and exotic tomes of scholarship. I knew then and there that I wanted that for myself.

When I was older, and indeed had upholstered my rooms with books, I also knew I had to unload some of them. It was too much. Not only were the shelves full — so much that they no longer functioned as decor, but as hazard — the floors, tables, chairs and refrigerator were also piled with books. If nothing else, the cat was in danger of being killed by a bookslide, an avalanche of tumbling paper and leather that might squash the poor beast into a stain of blood and fur on the hardwood floor.

The periodic cull was called for. Going over the collection and deciding, strictly, that one-in-ten or two-in-ten just had to go. Box them up and take them to the used bookstore for credit. Or donate them to the library book sale. Or drop them unannounced somewhere worthy.

When we lived in Arizona, we piled the car full of these overages and drove to the Gila River Indian Community at Sacaton, about 50 miles south of Phoenix. We came to the old wood-frame building that functioned as the community library. It was closed. I jimmied the door open, carted about 10 boxes in, left them by the front desk with a note saying, “The midnight skulker strikes again.” And left.

A few years later, we thought we’d do the same thing with a new set of supererogatory volumes. Drove to Sacaton. Found the library. But lo, they had responded to our first visit by adding a deadbolt lock to the front door and a chain-link fence around the building. So, we had to leave our books on the front stoop. And left.

But no matter how many times we culled, how many library sales we added to, we always seemed to refill the cup almost instantly with new books — or newly purchased used books — often from the same library sale we had given to.

It wasn’t only at home. At my carrel in the newspaper office where I worked for a quarter of a century, a bookshelf half-blocked the passageway behind my desk and the whole flat surface on which my computer rested was also piled high with reference books. The paper had a perfectly good library and three librarians to help with research, but I still felt that in my particular field — art criticism — I needed my hundred specialized books. (In my last years, the research was largely transferred to Google and Wikipedia and so the books became more of a fashion statement than a resource).

There was a moment, after a divorce (this is a common story), that I decided I should pare my belongings down to the essential, following the crank advice of Henry Thoreau. I would lose all the excess accretion of years and be able to carry all my belongings in a single rucksack. I had decided that the only two books I needed were a Shakespeare and a Bible. These were the foundations on which all else was built.

Of course, it never worked out that way. Even when my lady friend and I decided to take six months and hike the Appalachian Trail, and weighed every ounce of our equipage, I still managed to pack a complete Milton.

Yes, it’s a disease. But there are good reasons for the libraries that so many of my friends and relatives also keep. At least four.

The first and most obvious is for reading. If you read a lot, you will naturally find your collection growing. Some people manage to obviate this impediment with a library card. For such people, the pile of books gets replaced weekly or biweekly with a new pile.

But, if you believe that reading requires underlining and the writing of margin notes, well, the local librarian tends to frown upon such vandalism. So, you must own the books, keeping them after you have read and responded to them. Anyone who reads regularly knows that books tend to spread in the house like kudzu. It is these books that you must force yourself to cull periodically.

Second, books are needed for reference. Especially if you are a writer, you know you occasionally need to look up a quote, a favorite passage, or at least to cite the birth or death date of someone you reference in the writing. For an art critic, it also means a ton of art books, so you can find a particular painting by Monet or Fra Angelico. You might need to remember if the house behind Christina is painted white or left weathered wood, or if there is a cat or a bear cub sitting in the front of the dugout canoe in George Caleb Bingham’s Fur Traders on the Missouri (comparison with an alternate version of the painting in Detroit makes it seem more ursine than feline).

Both of these initial reasons for keeping books are built on utility. And there is no doubt, the usefulness of books should not be sniffed at (although the smell of books is one of their addictive qualities).

A third reason for keeping some of these books is the emotional investment you may have in them. This book was given to you by your grandmother — that’s never leaving the house — or that one was a birthday gift from someone you loved who is now dead, or this one was the first book you ever owned, when you were in third grade and were wild about dinosaurs. You can have emotional attachments to books just as you can with people, or rather, the books are a ghost of the people you have cared for.

A corollary to this is the problem of once having culled a book you thought you were over, you spend your time and treasure years later re-acquiring it. Sometimes my only reason for spending an afternoon in a used bookstore is the hope you might glimpse a long-lost book you wish to god you had never dumped.

A fourth reason is the neurosis of the collector. A good quarter of the books I own are parts of such collections. I have dozens of books about the photographer Edward Weston. I have loved his work since I was an adolescent and have not only many photobooks filled with his images, but some rarer books: The Cats of Wildcat Hill, California and the West, My Camera on Point Lobos, a reprint of his book illustrations for Walt Whitman: Leaves of Grass. Several of these have actual financial value.

Another collection is of books from the Library of America. One whole floor-to-ceiling shelf is filled with the blue, green or red clothbound beauties from that publisher, each handsome and beautifully printed. I cannot afford them new, but I sconch any one I see used when I am scouring the used bookshops.

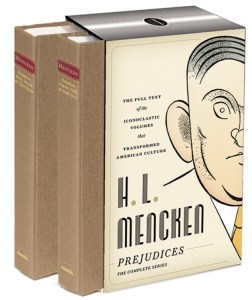

I also have complete, or nearly-complete collections of the works of William Faulkner, D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Herman Melville — and I am beginning to load up on H.L. Mencken.

The sin of the collector, of course, is completism. I am not quite so nuts that I want first editions, or all editions of certain books. A single copy of each work is enough for my completist heart.

There are no doubt other reasons for filling your home with volume after volume. But if nothing else counts, it should be enough that books are a delight. Not only their content, but the feel, heft, the buckram or linen, the morocco or half-leather, the gold print spine, the marbled endpapers, the scarlet headband, the deckled or gilt fore-edge, the texture of slight embossment that lead type presses into the paper, the sound of a turned page.

Although none of this matters like the world-wiping ability of reading the books to give you access to places, thoughts, cadences, structures, values, opinions, insights, that you would never otherwise be privy to.

If there is a problem that I face now, it is what will become of these friends when I am gone? A collection of books is so personal that they, together, make up a portrait of their owner. There is a reason Thomas Jefferson’s library was kept intact to form the basis of the Library of Congress. Mine, of course, is not so reverend, and there is no one who has any use for this particular selection of volumes. What is lifeblood for me, would be a burden for anyone coming after, having to disperse my estate. And my estate is almost entirely bound up in bound volumes.

In the meantime, I am not yet going anywhere, and my books are my dear companions.