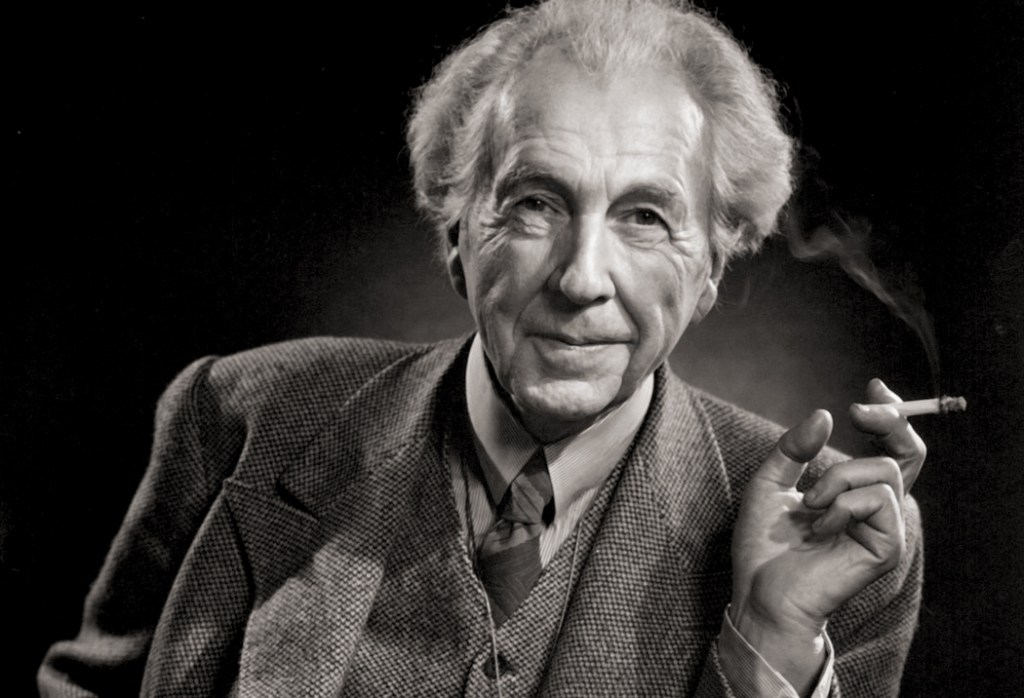

Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the greatest architects in history, and he’d tell you so, himself. The man in the cape and porkpie hat had an ego as big as any of his buildings, but as they say, if it’s true, it ain’t bragging.

It is so tempting to dismiss Wright. He was a monster of egotism. His taste could be appallingly bad. He spoke in egregious platitudes. He abandoned children and wives. He was arrested for violating the Mann Act. He made life a misery for almost everyone around him. And what is worse: His roofs leaked. For an architect, that may be the worst sin.

But no matter how irritating, Wright cannot be dismissed. It matters not that he insisted he was the greatest architect in American history. (“Why limit it to America?,” he then asked.) The fact remains that no architect of our time — and probably not of any other time — has had so fertile an imagination or produced so many outstanding buildings.

That is undoubtedly the most infuriating thing about Wright: He didn’t only talk the talk, he walked the walk.

“I hated him, of course,” said waspish architect Philip Johnson, “but that’s only normal when a man is so great.”

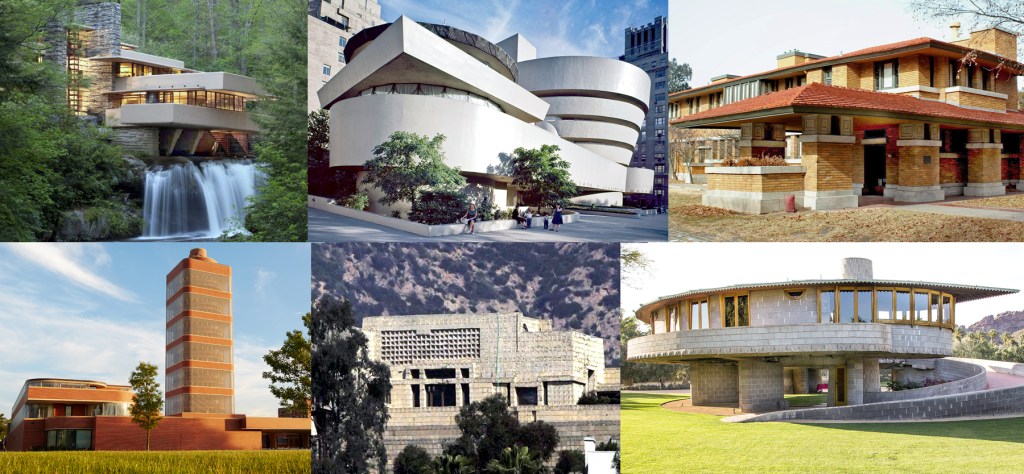

From his early Prairie Style homes near Chicago to his giant spiral Guggenheim Museum in New York, Wright kept inventing new ideas. “Why, I just shake the buildings out of my sleeves,” he once said.

The man is difficult to pin down because, not only did he change constantly over his 90-plus years of life, he also notoriously lied about everything. He was always making orotund pronouncements and declarations, but not a one of them stands without careful checking.

England has its eccentrics, its beekeeping vicars and parish historians, but America requires something more grandiose.

America has crackpots.

The crackpot differs from the mere eccentric in his missionary zeal, his transcendent ego, his absolute certainty and his touch of utopianism. From Henry Thoreau to Ezra Pound, from Charles Ives to Harry Partch, American art and culture have been defined by crackpots. Something in the American character warms to them. Something of the best of America can be found in them.

It is important to remember that. So much has been written and said about the architect, and with such reverence and hype. It is not that I mean to debunk Wright; he was a singular genius and must be recognized as such.

But he also was a true American crackpot, and we need to remember not only the dynamic imagination and idiosyncratic design, but also the odd geezer in the black cape and cane who wrote crank letters to the president. We need to remember the despotic man who installed glass bars instead of windows in his most famous industrial commission, Wisconsin’s Johnson Wax building, because he declared, “No one should have to look out at Racine.”

There are several things that join to make Wright’s work justifiably the most celebrated by any American architect. First among these was his uncanny sense of space.

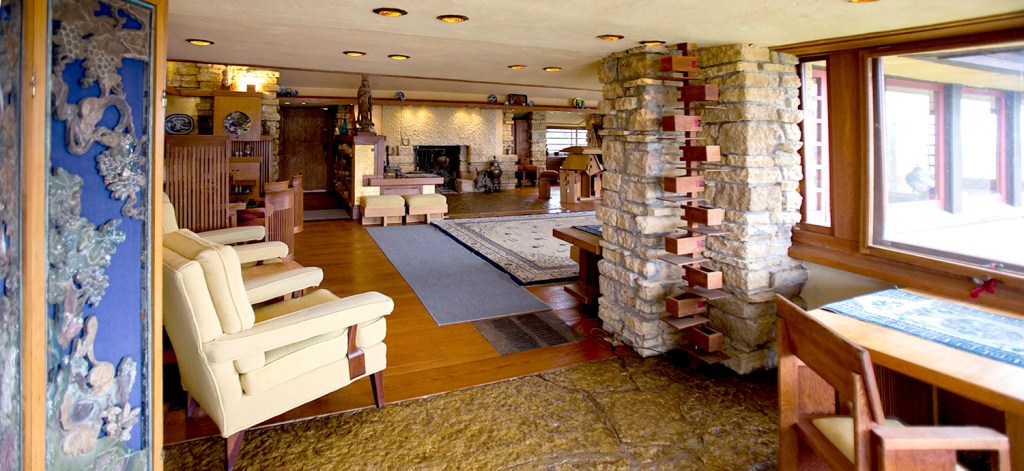

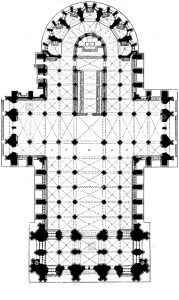

What makes architecture work, and particularly Wright’s architecture, is the shape of its insides, the particular chunk of air it surrounds with walls. To experience architecture is to walk through it, sit down in it, see where the space seems to grow and shrink as you pass through.

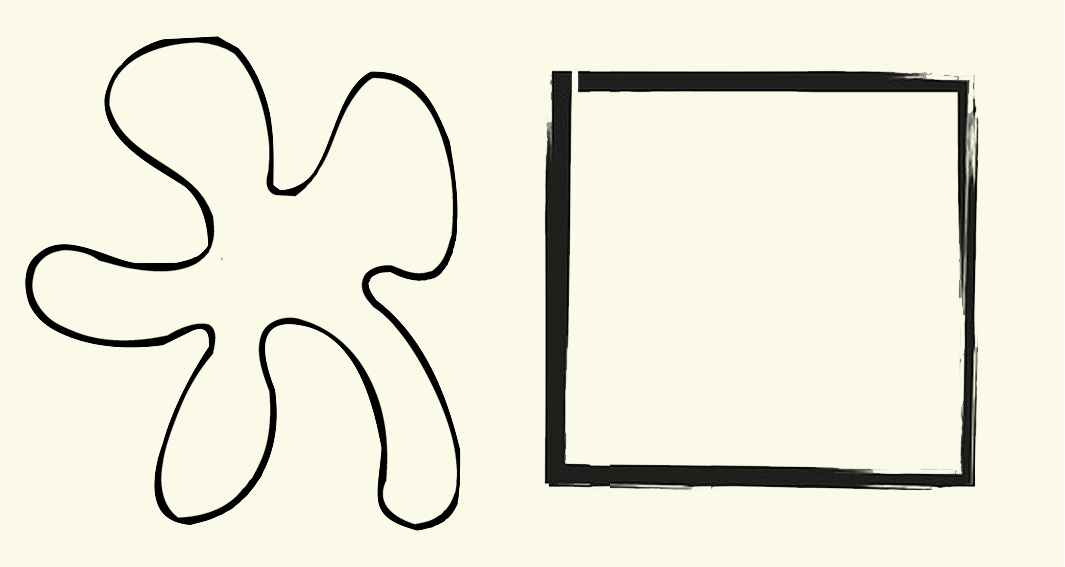

So many of us live and work in simple boxlike rooms — little boxes inside bigger boxes — we don’t always remember that rooms don’t have to be that way. “Break the box,” was one of Wright’s war cries. And in his buildings, he constantly did just that. Instead of boxes of rooms off a hallway, Wright created vast open spaces, one room opening into another. In his own home, called Taliesin, in Wisconsin, you can stand in the center of the house and see out of it in all four directions.

Wright recreated for us that sense we had more easily when children that space can have emotional meaning, building “forts,” or climbing in tree houses of discovering caves in the hillsides. Adults can have those emotions, too. And great architecture can provide the adult emotions that are analogous to those childhood ones. I can write about thoe spaces and you can see pictures, but pictures of them don’t do it. You can only have those emotions when standing in those places.

Even with his earliest buildings, the Prairie style homes, he attempted to reduce the number of rooms and create large flowing spaces, part of which might serve as dining area and part as living room. They would be built at different levels and sometimes at different angles, all to obliterate the hated “‘box.” In his best buildings, you can feel as if you are standing outside when you are actually indoors, and indoors when you are out.

The second great strength of Wright’s work is its unceasing originality. Wright ideally approached each design as a completely new problem, to be solved in its unique way. This means that, unlike the work of his great contemporary Mies van der Rohe and his International style, there is not, after the Prairie style, a single “look” that can be identified as Wright’s. For Wright, “what we did yesterday, we won’t do today.”

Mies groused back, “You don’t start a new style each Monday.”

But because he did start out each Monday, Wright has given us a startling variety of invention. It is true that not all the work is of equal value, but it is hard to find another artist in any medium who so thoroughly reinvented himself with each idea.

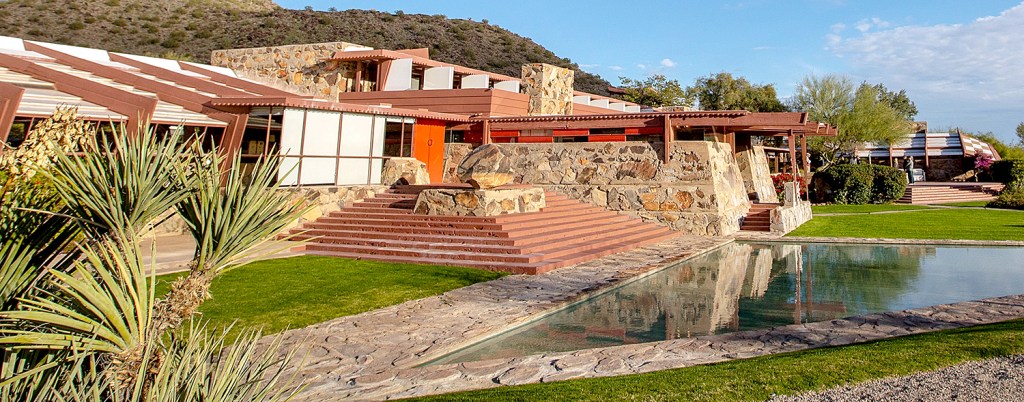

I was architecture critic for most of my 25 years living in Phoenix, Ariz., where Wright had his second home and architecture school later in his life (Taliesin West in Scottsdale), and I was immersed in Wright hype and legend. I got to visit many of the most notable Wright buildings across the country, and I came to recognize and value his genius (there really is no other word for it), but I also came to know and loathe the man himself. I will try to do justice to both.

Architecture has four main components. First, there is the sculptural aspect, the shape a building cuts. It is what most people think of as architecture: the building as seen from the outside.

Second, there is the engineering. Wright was both an innovative engineer and an occasionally casual one. His innovations are myriad; his lapses legendary.

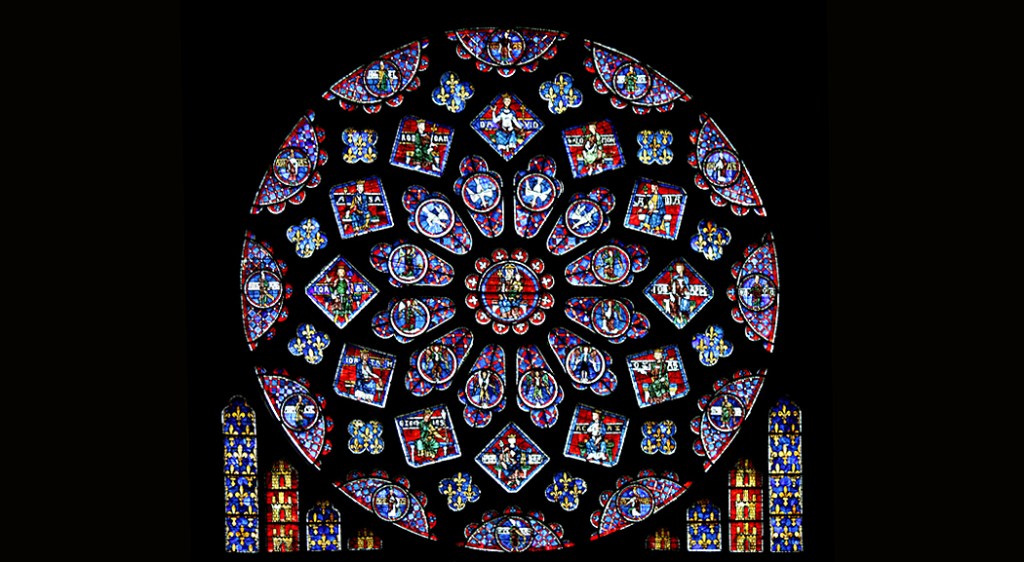

Third, there is the interior design aspect. Early in his career, Wright was especially good at this, and it is the part of his work that comes across best in photographs. The windows, the tables, the carpets he chose are beautiful, refined and subtle. Later in his career, his design became garish and loopy. But it is still what people know best.

But the fourth part of architecture is arguably the most important aesthetically. It is the essence of architecture: the emptiness inside. And Wright’s particular genius is his way with space, the way he orchestrates large and small spaces, to stimulate your emotions as only great art can.

Wright was especially concerned with how one room led to another, how a low ceiling makes you feel, or how nooks make magic. He called space “the invisible fountain from which all rhythms flow and through which they must pass.” These are things that cannot be conveyed in pictures; you have to be there, in the rooms, to sense their splendor.

It is like pictures and writings about Beethoven: No matter how good the text, it cannot tell you what the music sounds like. You have to experience it. So, photographs still cannot show its readers what truly made Wright the special case he was. No one invented interior space more creatively. Wright was not merely inventive, he was revolutionary. On the scale of Stravinsky, Picasso, Brecht or Eisenstein.

People easily mistake the outside of a building as its “architecture.” For most people, architecture is a kind of very large, inhabitable sculpture. And there is certainly that aspect to the art. We recognize the Chrysler Building immediately, or the U.N. Building, from their outsides. But how many people can say what the insides of these buildings look like?

Wright’s essential genius was not that of a sculptor. In fact, some of his buildings are almost ugly. No, his genius was for the empty space inside a building. He changed utterly and forever our idea of what an interior could be. Wright was a creator of empty spaces. Really interesting empty spaces. He approached a building with the air inside it as a kind of armature for the exterior.

He found 2,000 years of architecture in which square rooms inhabited square buildings, one set of cubes inside a larger one, and broke it open, breaking down walls and finding new ways of dividing the space enclosed by the exteriors.

Like Stravinsky or Picasso, Wright constantly changed styles, from the Prairie Style of his early residences to the “Planet Mongo” style he sometimes devolved into in his later years. But like Stravinsky and Picasso, the style itself was never the point. Stravinsky may rush from the lush Firebird to the astringent L’Histoire du Soldat, but underlying it all is an irony. You cannot imagine Stravinsky without the irony. Picasso has his plastic inventiveness — that shows through whether he’s doing Cubism or Neoclassicism.

And Wright always has his empty spaces. Every corner you turn brings a discovery: a room bigger or smaller than you expect, a space that stretches out in interesting ways, or closes you in and makes you cozy. You can like or dislike the decorative style in which Wright worked, but you cannot help but be astonished at the way he makes you feel inside a space.

He was born in Wisconsin in 1867 and began work in the Chicago area in the 1880s, soon becoming one of the most innovative and stylish architects working. His Prairie Style homes from the early 1900s became his signature look.

But by 1909, the 42-year-old wunderkind felt he was losing his grip on his work, “even interest in it,” he wrote. So he left his wife and six children and ran off to Europe with the wife of one of his clients. The scandal affected his practice, and Wright moved into a period of relative obscurity. He built his first Taliesin in 1911 as “a hope and a haven” for himself.

Many artists have written their autobiographies, but Frank Lloyd Wright built his. It sits near the top of a hill in southern Wisconsin near the town of Spring Green and looks out over farm fields and forests. Wright titled his architectural autobiography “Taliesin.” It was his home.

But three years later, that first house burned down in a tragedy of epic proportions when a workman went berserk, took an ax and slaughtered Wright’s mistress, two of her children and four other people, then set fire to the building. Wright was out of town at the time. The scandal was front page news across the country.

He rebuilt immediately. The blow left him numb, but, as he wrote, “There is release from anguish in action. Anguish would not leave Taliesin until action for renewal began. … Steadily, again, stone by stone, board by board Taliesin the II began to rise from the ashes of Taliesin the first.”

And so did Wright’s career. He took a new direction once more, a commission in Tokyo to build the Imperial Hotel, which opened in 1923.

In 1925, a second fire razed Taliesin. Again, he built it up, even using stones from the first two incarnations in the walls of the third.

He went on to design some of the landmark buildings of the century: the Johnson Wax Building in Wisconsin and Fallingwater, a summer home for the Kaufmann family, in Pennsylvania, and a long series of distinguished private and public buildings.

Many of the design and engineering innovations he used in those buildings had their “off-Broadway” run at Taliesin, as Wright built and rebuilt the house. By his own account Taliesin was never finished.

It is one of the most beautiful houses I’ve ever seen. Every angle and corner has something rich and meaningful to give up. One of the other party tricks Wright pulls on us is that, however stunning the living room is while you are standing in it, it is even more glorious when you sit down. Then, the long walls of windows become frames for the landscape outside. Standing, there is greenery, but no horizon; sitting, the horizon cuts halfway through the glass frame, making the windows like another spread-out Japanese screen.

The house is amazing. Wright always said he wanted to “break the box,” by which he meant he wanted to avoid the sense that each room had four walls and a door. So he opened up his house. It is rare to find a corner, for instance: When you approach what looks like a corner, it opens up to display some unexpected nook or hallway. So that, at dead-center of the house, you might almost be standing outdoors: There is a four-direction view.

At that point, standing in the hallway just where it opens into the den, you can look to the north through the living room and see the Wisconsin hillsides; then turn to the east and see more through that room’s glass walls; then turn south and peek through the distant windows of Wright’s office and bedroom, to see the hillside with the house called Tan-y-deri and the windmill that pumped the estate’s water; then, finally, turn west and see the top of Taliesin’s hillside and the garden and greenery surrounding the tea circle where Wright and his apprentices met for discussion.

Almost any room you enter will require you to duck and scrunch down as you worm through the hallway or entry or door and then feel the weight of the universe lifted from you as the room expands upon your entry. It is a party trick, no doubt, but one Wright plays with great relish and effect.

I could go on, waxing ecstatic over other Wright buildings I have visited, from Fallingwater in Pennsylvania to the Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael, California. I have always been astonished by what I saw. But there is the other Frank Lloyd Wright, the liar, cheater, fraudster and prophet of some of the worst developments in civic life.

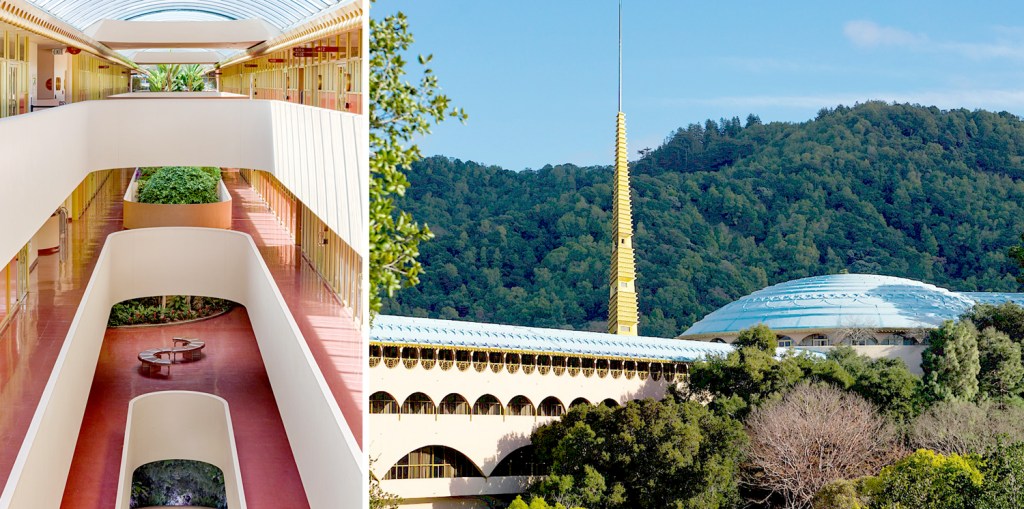

The shopping mall concept, it can be argued, began with a government building by Wright. In 1957, the equivalent of a Steven Spielberg “mother ship” landed on a woody hillside in San Rafael, Calif. It was the Marin County Civic Center and, from the outside, it was one of Wright’s “Planet Mongo” designs — odd, ungainly and a model of kitsch.

But inside … inside it was truly original. It placed the county governmental offices several stories high along the outer walls of the complex, with balconies running the length of the building overlooking a pedestrian walking space. You could look down at the “storefront” offices and the ferns and plantings along the fountains and escalators.

When you visit the building, you can’t help but think: shopping mall. Brilliant, but I don’t know how grateful we should be for all the soulless malls we find filled with T.J. Maxes and Sbarros.

That Flash Gordon esthetic increasingly began to take over Wright’s design esthetic as he got older. In his early years, Wright was at the forefront of Modernism in architecture and his best work — those Prairie-style houses, the Johnson Wax building — have remained ever fresh and new. But in his senescence, many of his designs have become dated, like those futuristic book illustrations filled with dirigibles and autogiros.

Instead of modern, he became what might be called “modernistical.” As in his design for the First Christian Church in Phoenix, with its science-fiction spires and reptile-scale roof.

Then, there was Wright’s hatred of cities — an odd opinion for a builder of buildings. He called them “a persistent form of social disease,” and when asked in Pittsburgh what could be done to improve the city architecturally, he replied, “Tear it down.”

And he singled out New York for special opprobrium, biblical in its rancor. He compared it to Sodom and Gomorrah, complained that it was the city of Cain. He called it “a pig pile. A fibrous tumor. Is this city not Anti-Christ?” and said it was “a place fit for banking and prostitution and not much else.”

He once said the only logical place to build a skyscraper was in the desert, where the height could afford a view worth seeing. And he designed a skyscraper a mile high, never built, of course.

“Mile-high? Why stop there? Why not two miles, or even five miles, if need be?” he asked a friend. (The irony is that the Burj Khalifa, which is a quarter-mile high, was built in the desert, and although not designed by Wright, did borrow his plan for making the footprint of the building a triangle, giving it the stability of a tripod).

The fruit of this dislike was a vision of suburbia. Wright cannot exactly be said to have invented the suburban prototype Levittown, but he certainly predicted it in his 1932 plans for the fictional Broadacre City. Wright envisioned a sprawling suburbia, created out of minitowns, or self-contained neighborhoods, linked by automobile and tree-lined roadways.

If the thrust of American growth was upward, Wright cast his vote for outward. But we now live with the results of that thinking: It’s most extreme embodiment is Los Angeles, sprawling neighborhoods over an area the size of some Eastern states. It is Broadacre City metastasized.

Wright was as bad as Wagner when it comes to breaking up families. In the 1930s, the architect left his wife and six children and ran off to Europe with Mamah Cheney, who was the wife of one of his principal clients. Wright was notorious, at least in his younger years, for having the sexual morality of an alley cat.

He was a monster of self-regard. “Not only do I fully intend to be the greatest architect who has yet lived, but fully intend to be the greatest architect who will ever live. Yes, I intend to be the greatest architect of all time,” he wrote.

There is a famous TV interview with Mike Wallace, from 1953, where the man spouts off in the most irritatingly smug fashion, about his own greatness. When Wallace asks him if he said something about being the greatest architect of the 20th century, Wright answered, “You know, I may not have said it, but I may have felt it.” Actually, he did say it, many times. He also wanted to claim humility as one of his great virtues.

Much of the interview is a piling up of fatuous truisms and platitudes. “The answer is, within yourself.” That kind of thing, but spoken as if he were giving us pearls of wisdom from Zarathustra in his mountain cave. (The interview is available on YouTube.)

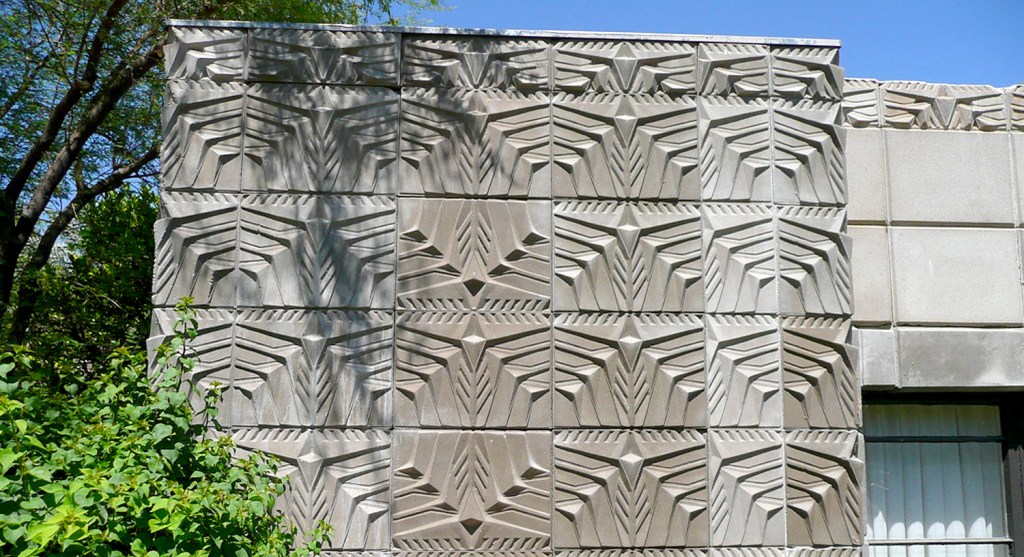

Nothing sums up his dabbling in fraud and mendacity as his involvement with the construction of the Arizona Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix. It was opened in 1929, designed by architect Albert Chase McArthur. Yet, tourists visiting Arizona are often told that the Arizona Biltmore was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. It wasn’t, although, as we’ll see, Wright sometimes took credit.

There are two things to note about the resort and hotel. First is that Wright was given $10,000 as a license fee by McArthur, for permission to use the patented “textile-block” technique. Problem was, the patent wasn’t Wright’s. It was invented elsewhere by others. Wright had previously used the technique and found no reason to disabuse McArthur of the idea the technique was his to license. Wright was later sued by the true patent owners and had to pay up.

When McArthur contacted Wright about using the textile-block system, the Chicago architect telegraphed back that he would be there immediately, and in January 1928 he showed up at the door.

In another of the changing stories, Wright’s stay in Phoenix stretched out longer and longer. Early sources say Wright was here anywhere from a few weeks to a few months. A little bit later, Wright claimed he worked on the Biltmore for six months. And in a public speech made a few years before his death, he claimed, “I spent a whole year at it.”

In reality, the visit was probably less than a week, after which McArthur had had enough of the overbearing Wright and sent him packing.

“The contractor was complaining about his interference,” McArthur says, “and when Wright refused to pay his rent for the house he was living in, they came with the police and evicted him. Wright said, ‘I don’t have to pay rent; I’m Frank Lloyd Wright.’ ”

McArthur had previously worked for Wright in Chicago from 1909 to 1911, performing various jobs and soaking up the influences. He later set up a practice of his own there.

It is one of the marks of Wright’s tenacious mendacity that each time he later recalled McArthur, Wright’s memory of McArthur’s tenure with him got shorter, until, late in his career, Wright claimed that McArthur “had spent a few months” with him.

It is important to note this, because Wright’s lack of generosity to his fellow architect becomes a major part of the Biltmore story, and a contributor to the mythology.

Wright’s version of his participation in the design also changed over the years. Shortly after the hotel opened, he wrote a letter saying, “Albert McArthur is the architect of that building. All attempts to take the credit for that performance from him are gratuitous and beside the mark.”

In fact, Wright thought the hotel was a botch. He criticized the building as “even worse” than he had imagined. “Far from being a great work of art, (it is) lacking even the most primitive elements of good design.”

Yet, when the hotel became popular and its architecture praised, Wright changed his story. In his notoriously inaccurate and self-serving autobiography of 1943, he appears to see himself as the master architect working sub rosa for the “architect of record.”

And in a lecture in 1957, he answered a woman’s question by saying, “This lady wants to know if I designed the Arizona Biltmore hotel, and I did.”

Wright went on to tell the audience, “There was a young student of mine who had the commission. He never built anything but a house, so they sent for me to help out and I helped out. So that’s the Arizona Biltmore.” Of course, by that time, Albert Chase McArthur had been dead for six years and could hardly defend himself.

Mendacity the great speed bump of Wright’s personality: arrogant, often supercilious, egocentric and selfish. Wright could belittle those around him, fail to acknowledge their contributions, and he could be frustratingly patronizing. He lied, committed fraud, failed to pay bills. Biographers have been unraveling the lies he told about himself for years.

When Brendan Gill wrote his 1987 biography of Wright, Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright, he had to spend a good deal of his time debunking Wrightian lies. The architect used to tell the story that when his mother was pregnant with him, she had already decided he was going to be an architect and hung his nursery with engravings of English cathedrals cut from a magazine. Yet, the magazine engravings in question weren’t published until Wright was a teen-ager, and the tiny house they lived in at the time was too cramped to have a nursery.

He even lied about his name: He was born Frank Lincoln Wright.

He was a monster. We are unfortunately too familiar these days with the concept of the malignant narcissist. Yet, there is an important difference: Wright was also a genius.

When I go to any decent-size bookstore, I can find one or two books about any of the names you read about in architecture — Rem Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Frank Gehry, Norman Foster — but there are two-and-a-half shelves on Wright, and he’s been dead for 65 years.

ENVOY

It has become common to conflate artists with their work. And artists are rarely angels. If we no longer watch Woody Allen movies, or appreciate Picasso’s paintings because their creators were fallible, even monstrous (Byron diddled his sister; Shelley had a things for underage girls; Wagner was a vicious anti-Semite) then we are likely to be required to excise more than half of all of the creations of civilization — maybe all of it, depending on where you draw the line.

Caravaggio was a murderer; Lewis Carroll enjoyed taking photographs of nude little girls; Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Hector Berlioz were drug fiends. They — and we — are all human and bundles of contradiction. For their crimes, we may prosecute them, as we do anyone else. For their simpler sins, we develop short memories. For what they have given us, we need to be grateful.

Click on any image to enlarge